This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

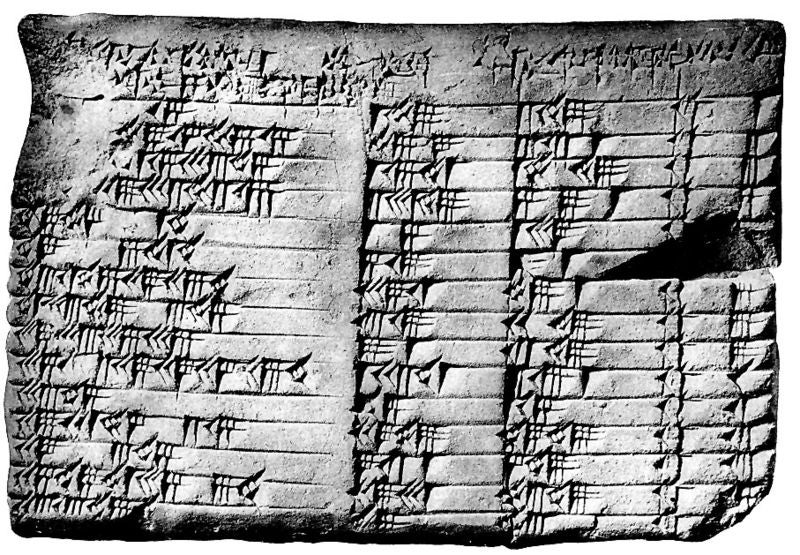

Plimpton 322, an ancient Mesopotamian mathematical tablet whose purpose is still a mystery. Image: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

As I told my class on Thursday, the theme of the first week of our math history course was “easy algebra is hard in base 60.” We started the semester in ancient Mesopotamia, trying to understand Babylonian* mathematical notation and decipher Plimpton 322, an enigmatic tablet from about 1800 BCE.

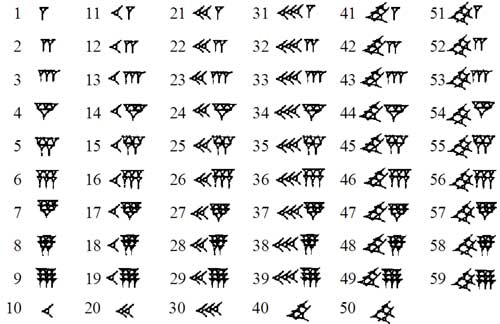

The Babylonian number system uses base 60 (sexagesimal) instead of 10. Their notation is not terribly hard to decipher, partly because they use a positional notation system, just like we do. To us, the digit 2 can mean 2, 20, 200, or 2/10, and so on, depending on where it appears in a number. 25 means “two tens, five ones." 52 has the same symbols, but it means "five tens, two ones." Similarly, 1,3 in sexagesimal means “one sixty, 3 ones,” or 63, and 3,57 means “three sixties, fifty-seven ones,” or 237.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The biggest difficulty my students and I had deciphering these numbers was not the fact that there were so many extra numerals to keep track of. In fact, that part was pretty easy. Unlike the Hindu-Arabic numerals we use today, Babylonian numerals “look like” the numbers they represent.

Babylonian numerals are surprisingly easy to decipher. Image: public domain, via sugarfish and Wikimedia Commons.

No, the biggest issue we had was nothing. Or more precisely, the lack of nothing. The Babylonians didn’t have a symbol for zero. And there's some logic to that. Why do we need a symbol that literally means nothing? But zero is what makes it possible for me to tell 1 from 10 from 1,000,000 from 0.1. Without it, the numbers we write are inherently ambiguous, and we have to use context clues to figure out what order of magnitude is meant in a given situation.

I should say that it’s not quite true that the Babylonians didn’t have a symbol for zero. In Plimpton 322, the tablet we studied in class, there are some gaps between numerals that represent zeros in the middle of a number, the way the 0 in 101 represents zero tens. Later, they added a symbol for zero, but it was only used for zeroes that were in the middle of the number, never on either end. That way they could tell the number 3601, which would have been written 1,0,1, from 61, which would be written 1,1. But 60 and 1 would always be written identically. They never made the leap to using a zero symbol at the end of a number to eliminate the ambiguity completely. The oldest documented zero is surprisingly modern: it’s in a temple in India, and it dates from about 875 CE.

One of the strange consequences of the lack of zero comes up in reciprocals. We usually think of reciprocals as number pairs like 2 and 1/2 that multiply together to equal 1. But Babylonian reciprocal tables, which made calculations quicker, listed any two numbers that multiplied to a power of 60 as “reciprocals.” For example, 5 and 12 are “reciprocals” in this sense because they multiply to 60. Why would this definition of reciprocal make sense? Because when you’re writing in base 60 without a zero, 60 looks just like 1! So do 1/60, 3600, and any other power of 60. It would be like us thinking of 4 and 25 as reciprocals because they multiply to 100. It would make some sense only if we didn't have a zero, so 1 and 10 looked the same.

Of course, there is a way to interpret the Babylonian symbols for 5 and 12 as reciprocals in the traditional sense, again because of the ambiguity that the lack of zero adds. If we interpret 12 as 12/60 (1/5), then we can multiply it by 5 to make 1. Or we could interpret 5 as 5 sixties (300), and 12 as 12/3600. Those numbers also multiply together to make 1. I don't know how the people who used this system really thought of reciprocals.

We spent some time in class calculating Babylonian “reciprocals,” (pdf) and it was surprisingly difficult. I kept telling my students that they were allowed to assume numbers had any order of magnitude they wanted. But we’re so used to numbers being completely concrete that the extra degree of freedom seemed to make things more confusing.

I told my students that the theme of the week was "easy algebra is hard in base 60," but that's not the real takeaway. The base isn't what makes calculations in base 60 difficult, it's the fact that mathematical culture of the people who made it is so different from ours. A more accurate slogan would be "easy algebra is hard 4,000 years later with a completely different view of mathematics," but it's not quite as snappy.

For more on Babylonian mathematics, see Duncan Melville's Mesopotamian Mathematics page. For more on Plimpton 322, visit David Joyce's math history site or read Eleanor Robson's article Neither Sherlock Holmes nor Babylon: A Reassessment of Plimpton 322 (pdf).

*I am using “Babylonian” and “ancient Mesopotamian” interchangeably in this post. Babylon was just one city in ancient Mesopotamia, but the usage is fairly standard.