This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

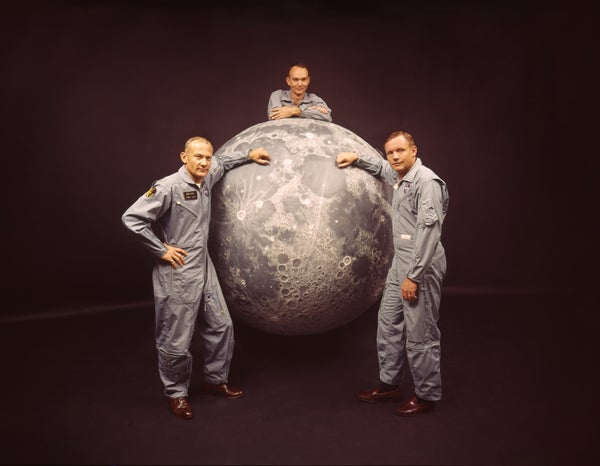

On July 16, 1969, Apollo 11 launched from Cape Kennedy. The astronauts on that historic flight were Commander Neil Armstrong, Command Module Pilot Michael Collins and Lunar Module Pilot Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin.

This year is the 50th anniversary of that flight. As part of this year's World Science Festival in New York City, I attended a talk, "The Right Stuff: What it takes to Boldly Go," where Collins and astronauts Scott Kelly and Leland Melvinwere among the speakers.

Listening to Collins talk, I recalled watching the moon landing with my dad on a little black and white television and hearing Armstrong say, "That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind."

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

I was 17 years old and one of an estimated 650 million people who watched Armstrong land on the moon and describe his experiences. What differentiated me from the other millions of viewers was that my dad worked for NASA and knew Neil Armstrong.

My dad, Arthur L. Levine, was hired as an administrator for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). This was his first "real job," which he began while finishing his dissertation for his PhD in political science at Columbia University.

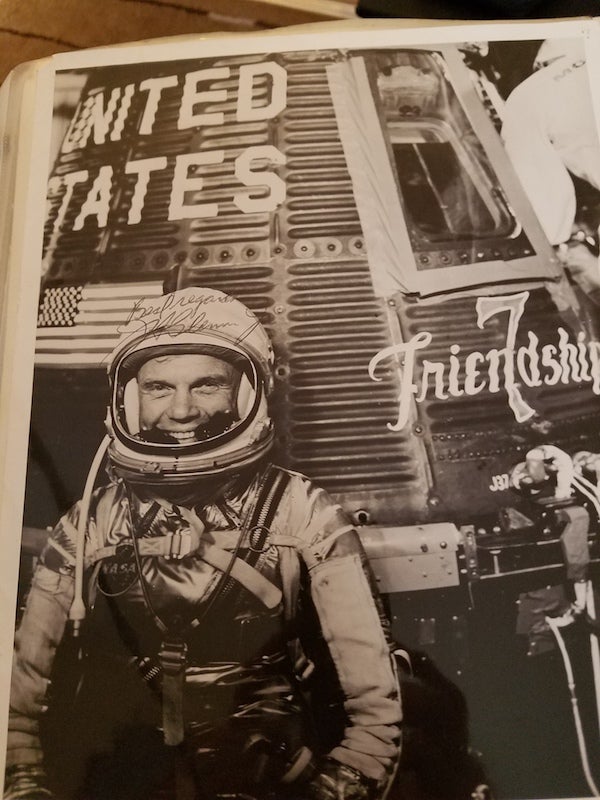

At the Lewis Research Center in Cleveland (later renamed the Glenn Research Center), he recruited engineers for the space program. His time in Cleveland coincided with both Neil Armstrong and John Glenn, who like my dad (and me) were born in Ohio. Armstrong joined NACA in 1955 as an engineer and went on to become a test pilot, astronaut and administrator for NASA. Glenn, whom my dad recruited, trained at Lewis's Multiple Axis Space Test Inertia Facility (MASTIF) to learn how to control tumbling spacecraft.

In 1961, NASA established a think tank in New York City known as the Goddard Institute of Space Studies (GISS).

The author's father (far left) with Robert Jastrow (third from right, with his hand on his chin). Image courtesy of David Levine

My dad worked with Robert Jastrow, an astrophysicist, who was GISS's founding director. My dad was the executive officer. Both were in their 30s, and my dad told me Jastrow once said, "Do you believe NASA hired two youngsters to figure out how to get a man to the moon?" I got to know Jastrow well. A bachelor, he came to our house for dinner. When he was a guest on the Johnny Carson show he invited my family to be in the audience and took us to the Russian Tea Room. He also wrote a recommendation for college for me. I know it helped.

As GISS's administrative head, my dad recruited physicists to work at GISS including Jim Hansen, who started out as a postdoc in 1967 and was GISS director during 1981–2013. I remember asking my dad if he knew Hansen, whose comments on climate change made national headlines. My dad said, "I know him well. I hired him as a post-doc."

For a tribute to my dad, who passed away in 2015, I wrote to Hansen and asked him about my dad. He wrote me: "I had applied to GISS after seeing a poster on the wall of the Institute for Astrophysics in Kyoto Japan in 1966, where I was a visiting student and our professor did everything he could to prevent me from leaving. Art (my dad) was very good at sensing the situation—not sure if he ever received a recommendation letter from my professor—and accommodating my wishes for start time. Working at NASA GISS was special—it had the fastest computer in the world, IBM 360/95, which took up almost the entire second floor of the building—I would stay up until the middle of the night to run programs on it—NYC was a bit dangerous in those days—I was held up at knifepoint while walking back (at 2 AM) to the Paris Hotel on 96th Street."

Being a teenager and having a father who worked at NASA in the 1960s was very cool. My dad spoke to my science class, as well as my sister's. I visited GISS fairly often as it is near Columbia University, right above Tom's Restaurant, which is the exterior shot for the coffee shop where Jerry Seinfeld and George and Elaine and Kramer would meet. (There's a picture of the restaurant on GISS's web page.) Astronaut Scott Carpenter was a frequent visitor to GISS. I didn't get to meet him, but I did get to meet John Glenn when he helped launch the United Nations International Year of Older Persons at a meeting at the United Nations in 1998.

As a think tank, there's not that much to see at GISS. My dad took me with him on one of his trips to NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. I recall rooms filled with computers that seemed to stretch for miles.

Because dad worked for NASA, my fascination with astronauts and space flight has stayed with me as an adult.

In 2006, I was at a meeting in Cleveland that included a field trip to the Glenn Research Center, and got to see where my dad had worked. We heard members of NASA's Exercise Countermeasures Project discuss how they are preparing astronauts to cope with the loss of bone and muscle mass, strength and sensory-motor function caused by space travel.

And I have a great autograph collection.

Autographed photo of John Glenn from the author's collection. Image courtesy of David Levine