This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

How do you know your dog is conscious? Well, she wags her tail when she’s happy, bounces around like a young human child when excited, and yawns when sleepy— among many other examples of behaviors that convince us (most of us, at least) that dogs are quite conscious in ways that are similar to, but not the same as, human consciousness.

Most of us are okay attributing emotions, desires, pain and pleasure—which is what I mean by consciousness in this context—to dogs and many other pets.

What about further down the chain. Is a mouse conscious? We can apply similar tests for “behavioral correlates of consciousness” like those I’ve just mentioned, but, for some of us, the mice behaviors observed will be considerably less convincing than for dogs in terms of there being an inner life for the average mouse.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What about an ant? What behaviors do ants engage in that might make us think an individual ant is at least a little bit conscious? Or is it not conscious at all?

Let me now turn the questions around: how do I know you, my dear reader, are conscious? If we met, I’d probably introduce myself and hear you say your name and respond to my questions and various small talk. You might be happy to meet me and smile or shake my hand vigorously. Or you might get a little anxious at meeting someone new and behave awkwardly. All of these behaviors would convince me that you are in fact conscious much like I am, and not just faking it!

Now here’s the broader question? How can we know anybody or any animal or any thing is actually conscious and not just faking it? The nature of consciousness makes it by necessity a wholly private affair. The only consciousness I can know with certainty is my own. Everything else is inference.

So, where’s my consciousness-ometer?

These questions are more than philosophical. With the coming age of intelligent digital assistants, self-driving cars and other robots serving us and increasingly running our lives, does it matter if these AIs are actually conscious or just faking it?

Perhaps more relevant today, how can we know that coma victims, or patients in vegetative or minimally conscious states, are conscious or not?

This is an active area of research and for the poor victims in these categories, plus their families and loved ones, these questions are deadly serious. How can a family know whether to take a patient off life support or not, if they don’t know with any certainty what kind of consciousness is or is not present?

In my work, often with psychologist Jonathan Schooler at the University of California, Santa Barbara, we’re developing a framework for thinking about the many different ways to possibly test for the presence of consciousness—all using, necessarily, a process of reasonable inference.

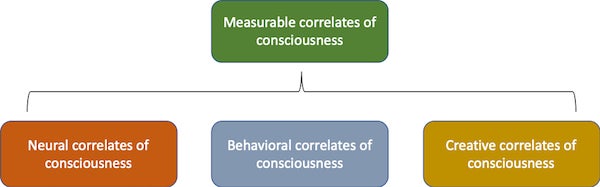

There is a small but growing field looking at how to assess the presence and even quantity of consciousness in various entities. I’ve divided possible tests into three broad categories that I call the measurable correlates of consciousness, or MCC (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. The various types of measurable correlates of consciousness (MCC). Credit: Tam Hunt

Let’s look at each of these categories in turn.

Neural Correlates of Consciousness and “Signatures of Consciousness”

When determining whether a vegetative patient is conscious in any way, we can and do examine the neural correlates of consciousness only, since there aren’t any behaviors to observe and no creative products either. Various researchers have proposed tests for cognition and consciousness in coma and vegetative patients.

What’s physically going on in the brain? Neuroimaging tools such as EEG, MEG, fMRI and transcranial magnetic stimulation (each with their own strengths and weaknesses), are able to provide information on activity happening within the brain even in coma and vegetative patients.

Stanislas Dehaene, a French neuroscientist, has identified four “signatures of consciousness,” which extend the idea of neural correlates of consciousness to more specific aspects of brain activity that are necessary for conscious awareness. He focuses on what’s known as the “P3 wave” in the dorsolateral cortex as the single most important signature of consciousness in humans. And in tests of vegetative and minimally conscious patients, he and his colleagues have successfully predicted which patients are most likely to regain more normal states of consciousness.

Sid Kouider, another French neuroscientist, has examined very young babies in order to assess the likelihood of them being conscious. He concludes (unsurprisingly) that even newborns are conscious in various complex ways.

Behavioral Correlates of Consciousness

When we are considering potential conscious entities that can’t communicate directly, and that won’t let us put our neuroscientific measurement tools on their head (if they even have heads), we need to consider behavioral correlates as clues for the presence and type of consciousness.

For example, are cats conscious? The brain architecture in cats is quite different from humans, and they have very minimal prefrontal cortex, which is thought to be the center of many higher-order activities of the human brain. But is prefrontal cortex necessary for consciousness?

Cat behavior is complex and pretty easy to map onto human behavior in many ways. The fact that cats purr, flex their toes and snuggle when petted, in similar ways to humans demonstrating pleasure when physically stimulated (minus the purrs, of course), meow loudly for food when hungry, and stop meowing when fed, demonstrate curiosity or fear about other cats or humans with various types of body language, and many other behaviors that we can easily observe ourselves if we have cats as pets, is all pretty convincing evidence, for most of us, that cats are indeed conscious and have a rich emotional life.

Creative Correlates of Consciousness

Creative output is another source of information for assessing the presence of consciousness. If for whatever reason we can’t examine neural or behavioral correlates of consciousness, we may be able to examine the creative products of consciousness for clues.

For example, when we examine ancient architectural structures such as Stonehenge or cave paintings in Europe that have been judged to be as much as 65,000 years old, are we reasonable in judging the creators of these items to be conscious in ways similar to our own? Most of us would say: obviously, yes. We know from experience that it would take high intelligence and consciousness to produce such items today, so we reasonably conclude that our ancient ancestors had similar levels of consciousness.

What if we find obviously unnatural artifacts on Mars or other bodies in our solar system? Do we reasonably infer that whatever entities created such artifacts were conscious? It will depend on the artifacts in question, but if we were to find anything remotely similar to human dwellings or machinery on other planets, but which was clearly not human in origin, most of us would reasonably infer that the creators of these artifacts were also conscious.

Closer to home, artificial intelligence (AI) has produced some pretty impressive art, fetching over $400,000 at a recent art auction. At what point do reasonable people conclude that amazing art creation requires consciousness? We can conduct a kind of “artistic Turing test” and ask study participants to consider various works of art and say which ones they conclude must have been created by a human. And if AI artwork consistently fools people into thinking it was made by a human, is that good evidence to conclude that the AI is at least in some ways conscious?

There is not yet a “consciousness-ometer,” but various researchers have suggested ideas, including Dehaene, and Italian-American researcher Giulio Tononi and his colleagues, who focus on “integrated information” as a measure of consciousness.

Neuroscientist Giulio Tononi and his colleagues like Christof Koch focus on what they call “integrated information” as a measure of consciousness. This theory suggests that anything that integrates at least one bit of information has at least a tiny amount of consciousness. A light diode, for example, contains just one bit of information and thus has a very limited type of consciousness. With just two possible states, on or off, however, it’s a rather uninteresting kind of consciousness.

In my work, my collaborators and I share this “panpsychist” foundation. We accept as a working hypothesis that any physical system has some associated consciousness, however small it may be in the vast majority of cases.

Rather than integrated information as the key measure of consciousness, however, we focus on resonance and synchronization and the degree to which parts of a whole resonate at the same or similar frequencies. Resonance in the case of the human brain generally means shared electric field oscillation rates, such as gamma band synchrony (40–120 hertz) as one example.

Our consciousness-ometer would, insofar as it focuses on neural correlates of consciousness, look at the degree of shared resonance of various types, and resulting information flows, as the measure of consciousness. Humans and other mammals enjoy a particularly rich kind of consciousness, because there are many levels of pervasive shared synchronization throughout the brain, nervous system and body.

In our framework more generally, we propose a “weight of the evidence” approach to assessing the presence and nature of consciousness in any particular object of study. We ask a number of questions, in all areas of MCC as described above, to the object of study, and it answers in whatever ways it can. We then make the same kinds of reasonable inferences about the presence and nature of consciousness that we do every day when it comes to other humans or animals. This questioning process is meant to be truly general and could apply to any object of study.

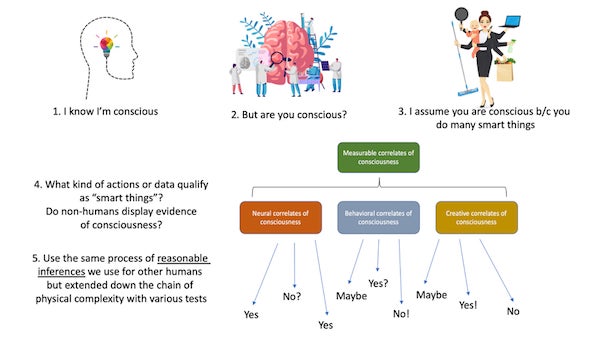

The logical chain of this framework is straightforward: I know I’m conscious; I assume you are conscious because you act a lot like me and do many smart things; I engage in similar reasonable inferences when assessing whether various animals are conscious and to what degree; we can use the same process of reasonable inference all the way down the chain of physical complexity. Figure 2 summarizes this approach.

Figure 2. Summary of our approach for assessing the presence and nature of consciousness in any physical structures. Credit: Tam Hunt

Tests for consciousness are still in their infancy. But this field of study is undergoing a renaissance because the study of consciousness more generally has finally become a respectable scientific pursuit. Before too long it may be possible to measure just how much consciousness is present in various entities—including in you and me.