This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

As of March 23, Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland have been able to contain the coronavirus, with fewer than 25 fatalities each. In contrast, the Lombardy region in Italy has experienced an almost exponential growth of the contagion, with nearly 3,500 deaths—despite it having roughly the same population as Sweden and about twice that of each the other Nordic countries. One likely reason for this difference is that, unlike Italians, Nordic peoples enjoy exceptionally high levels of social and political trust—that is, they are confident that their neighbors and their governments will behave responsibly. For example, a 2014 survey showed that 74 percent of Norwegians believed that “most people can be trusted,” whereas in Italy the figure was 29 percent. Similarly, 60 percent of Norwegians trust their political institutions, but in Italy only 21 percent do.

Trust is probably key to containing the pandemic. Governments around the world are seeking to limit the spread of the virus by imposing or suggesting restrictions on how people move around and interact. Some of these guidelines are difficult to enforce, so their success depends on the extent to which people voluntarily obey them. We are not supposed to meet with friends and family, especially those who are elderly or have some underlying medical problem. Just as important, we should not empty the stores by hoarding food and other necessities.

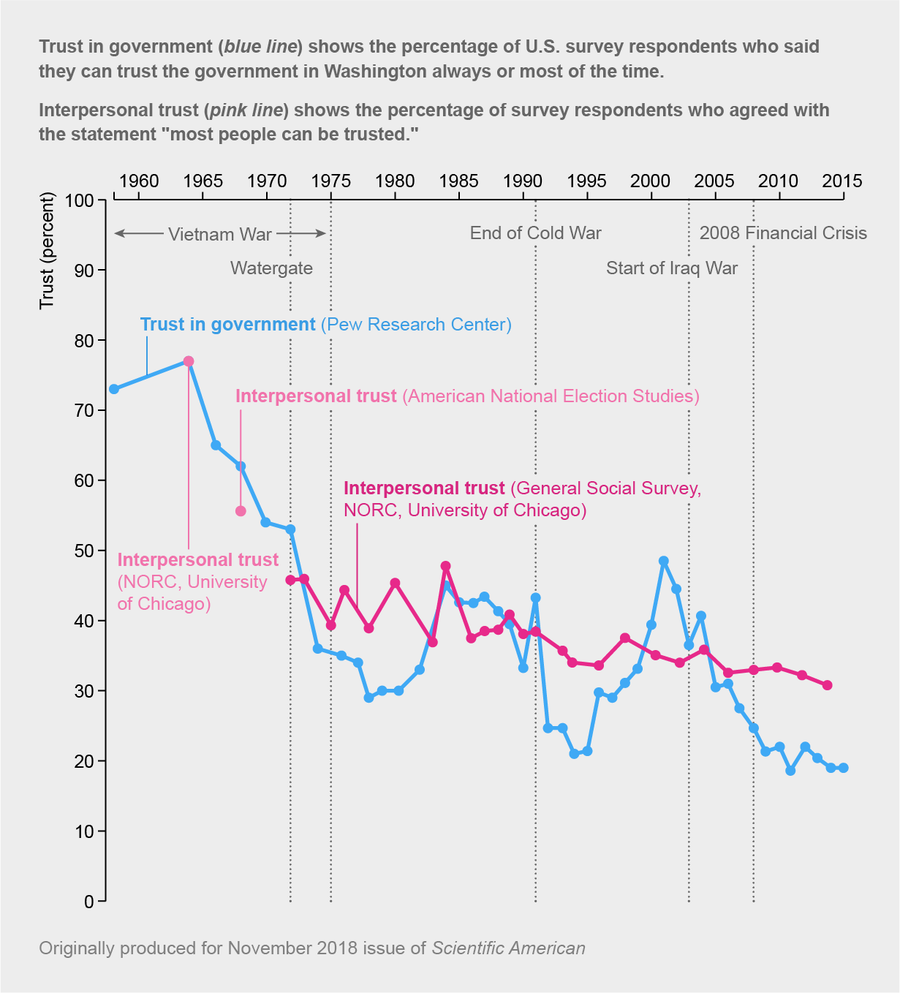

Credit: Amanda Montañez; Sources: Pew Research Center (trust in government data); American National Election Studies and General Social Survey, NORC, University of Chicago (interpersonal trust data)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The problem is that for the recommendations or regulations to work, we need to trust our fellow citizens as well as the government institutions that are issuing them. If people do not believe that most others are going to play by these novel and restrictive rules, they are unlikely to adhere to them themselves. That dismal conclusion comes from the so-called problem of collective action, well-known in the social sciences, which arises when actions that would lead to the common good seemingly conflict with those that advantage the individual. A famous example is the “tragedy of the commons,” first identified with shepherded animals overgrazing public lands. In certain circumstances, those who pursue their rational self-interest generate worse outcomes for themselves than if they acted on a basis of reciprocity, expecting others to do the same.

Complicating the problem are self-fulfilling prophesies, as described by sociologist William Isaac Thomas in 1928 by the sentence: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences.” Take the hoarding of food. If lots of people believe that hoarding has started, even those who are convinced that it is harmful are likely to start hoarding for fear of not having enough to eat. So, the lack of social trust will lead to an outcome that is worse for almost everyone: the stores will be empty, and not everyone can shop online. Worst off will be the elderly or the disabled, who cannot carry home enough supplies, or those who are too poor to buy lots of food at a time. The same goes for social isolation. If someone believes that most others in their community are not staying at home, it makes little sense for him or her to be in the minority that suffers loneliness.

Trust in the government is of course also necessary if citizens are going to follow the guidelines it is issuing. But people may have many reasons to distrust their politicians and administrators. Some might believe that they lack the necessary competence; others may think that those in power are not serving “the people” but instead are in a clandestine relationship with sundry economic and political elites. The new media situation also allows all kinds of conspiracy theories to flourish.

Crucially, both social trust and political trust vary greatly among nations and sometimes also within them. In China, for example, close to 80 percent state that they trust their government and about 60 percent believe that “most people can be trusted”—which may partly explain why, despite initial missteps, China could curb the epidemic rather quickly. Worryingly, however, the levels of both social and political trust in the U.S., which were high in the late 1960s, have since fallen substantially. Less than 40 percent of Americans trust one another and even fewer—about 20 percent—trust their government. These figures suggest that, in the absence of immediate trust-building measures by civil society and the government, the U.S. may find the pandemic exceptionally difficult to contain.

Related Article