This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

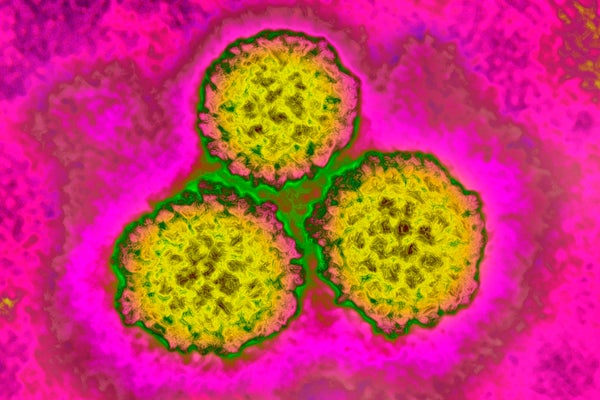

If you’re in a crowded room full of adults, look to your right and to your left. The person on each side of you—and you, too—have probably been, or currently are, infected with the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S. For most of us, our immune systems will clear the virus. But if yours fails to do so, and the virus remains in your system, it can cause health problems later in life, including six different types of cancer: cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancers in women; penile cancer in men; and oropharynx (back of the throat) and anal cancers in both women and men.

Every year in the U.S., HPV is estimated to cause over 34,000 new cases of cancer and according to the World Health Organization over 570,000 new cases of HPV-associated cervical cancer are newly diagnosed around the world each year. Since 2006 there has been an extremely safe and effective vaccine that can prevent these HPV-related cancers.

The HPV vaccine has typically been administered to girls and boys at the age of 11 or 12, because it is most effective when administered at an early age and prior to exposure to the virus. The original recommendations also encouraged men and women up to age 26 to get vaccinated. More recent recommendations from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration expanded the approval of the vaccine through 45 years of age for women and men who have not been previously vaccinated.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Following on the FDA recommendations, in June 2019 the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) also further endorsed this view and recommended that those who have not received the HPV vaccine and fall within the new age range should speak to their providers about the potential benefits of obtaining it. For those of us who were older than the original age cutoff of 26 when the first HPV vaccine was approved in 2006, this change was welcome. But insurance companies have lagged behind the FDA and CDC recommendations, and adults between the ages of 27 and 45 years are experiencing difficulties in finding primary care providers who administer the vaccine and in getting their insurance carriers to cover it.

Advocacy in Action

Faced with these barriers, we took our advocacy efforts to social media. When first rebuffed by our health insurance company for coverage of the vaccine because of age in November 2018, all it took was one tweet calling out the firm on social media and one follow-up e-mail to revise its coverage policy for our employer. The HPV vaccine became a 100 percent covered preventive benefit for those up to age 45 who work at our cancer institute.

After this initial success, the women’s group within our institution’s graduate school has also followed up on Twitter with other insurance carriers to advocate for HPV vaccine coverage for adults, with similar success. We encourage this kind of science citizen advocacy effort among anyone reading this article. If all it took was a few tweets and emails to get coverage for our colleagues and their families at our institution, why not inquire with your own insurance providers about whether they’ve adopted the new ACIP guidelines for covering the HPV vaccine up to age 45?

Following this development, our colleagues in human resources have worked with all the insurance plans offered within our institution to ensure that the HPV vaccine is fully covered not just for all who fall under the new ACIP vaccine recommendation but for anyone at any age older than nine. After reading this article, perhaps you, too, can lobby your HR partners to achieve similar coverage through your employer.

We both feel extreme gratification in knowing that we’ve prevented some of our colleagues from developing an HPV-related cancer, but our advocacy efforts aren’t simply confined to those within the biomedical realm. Publicizing the strengths and advantages of the HPV vaccine within a larger public—including neighbors, friends, family and elected officials—is a cornerstone of our work. And actively educating people about HPV and its transmission and epidemiology is just as critical as talking to them about the vaccine and its exquisite safety profile.

In fact, we’re supportive of New York State Senate and Assembly bills currently under consideration that would mandate HPV vaccination for seventh graders, as well as of bills currently under consideration that would allow adolescents to consent to the vaccine without parental approval. These kinds of decisions or policies have been enacted or passed by the local Departments of health in Virginia, Rhode Island, and Hawaii and in Washington, D.C. (states and regions whose HPV vaccination rates are among the highest in the country).

And they are under consideration in at least half a dozen other states. Public pushback has, so far, stifled these bills from passage in New York, given the strength and organization of opposition to even routine vaccination. It is time for scientists to be better prepared and more organized to fight against misinformation and to work with colleagues, friends and family.

Confronting the Anti-vaxxers

The rise of antivaccination campaigns is frustrating to all of us. But there are certain aspects of the HPV vaccine that make it an easier sell. For one, remind those who say the HPV vaccine will increase promiscuity in teens that they were required to vaccinatetheir infants and children against hepatitis B, which is a sexually transmitted virus. Vaccination as a child did not lead to their children’s early experimentation, just to the preservation of their liver.

This same concern has been studied for the HPV vaccine, with the exact same finding: no increase in promiscuity postvaccination. The HPV vaccine is a cancer-prevention measure, and we believe this message should be underscored and emphasized by all of us. We encourage providers to provide a strong, unwavering recommendation for this preventive vaccine to all their eligible patients.

Actively combating disinformation will be critical to the successful uptake of this vaccine and others. Concerns about the vaccine causing autism in children are overwhelmingly unsupported by scientific evidence and can be minimized, given that, in particular, the HPV vaccine is administered to adolescents and adults. The HPV vaccine has a strong safety record, with only minor side effects related to administration of the vaccine (pain, soreness and fever). This information is provided by the CDC’s and FDA’s Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS). For a further talking point, you can turn to coverage of a recent Lancet study that showed how safe and effective the vaccine has been. For example, in Australia, where the HPV vaccine enjoys robust uptake, cervical cancer could be eliminated in a generation.

Eliminating all cancer is a laudable goal yet is unlikely to be a realistic one. But eliminating HPV-associated cancers in a few decades is a realistic goal. We can only hope to achieve this goal with widespread uptake of the HPV vaccine, however. We hope that someday HPV vaccination will be a cornerstone of cancer prevention, just like mammography, skin checking and colonoscopy. Toward that goal, it is up to scientists, physicians and anyone reading this article to engage in advocacy efforts. Send those tweets and e-mails, talk to your neighbors and vaccinate yourselves and your children. Call an elected official, spread information and combat disinformation.