This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Cambridge Analytica’s wholesale scraping of Facebook user data is familiar news by now, and we are all “shocked” that personal data are being shared and traded on a massive scale. But the real issue with social media is not the harm to individual users whose information was shared, but the sophisticated and sometimes subtle mass manipulation of social and political behavior by bad actors, facilitated by deceit, fraud and the amplification of lies that spread easily through societal discourse on the internet.

Any pretense to privacy was abandoned long ago when we accepted the free service model of Google, Facebook, Twitter and others. Did the Senators who listened to Mark Zuckerberg’s mea culpa last week really think that Facebook, which charges nothing for its services to users, was simply providing a public service for free? Where did they think its $11 billion in advertising revenue came from, if not from selling ads and user data to advertisers?

Let’s identify the real issue. The tangible damage resulting from identity theft and the loss of personal financial information are growing problems, but they typically are not caused by our use of social media platforms, where we share a lot of information—but rarely our credit card or Social Security numbers.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The controversy about Cambridge Analytica that landed Zuckerberg before Congress actually began brewing over a year ago. It was a controversy not about privacy but about how Cambridge Analytica put vast amounts of personal data, mostly from Facebook, into its so-called “psychographic” engine to influence behavior at the individual level (see When the Big Lie Meets Big Data, published here in March of 2017).

Cambridge Analytica worked with researchers from Cambridge University who developed a Facebook app that provided a free personality test, then proceeded to scoop up all the users’ Facebook data plus that of all their friends (thus leveraging the actual users, who numbered less than a million, to harvest the data of more than 80 million people). Using this data, Cambridge Analytica then classified each individual’s personality according to the so-called “OCEAN” scale (Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism) and fashioned individually targeted messages to appeal to each person’s personality.

Neither subpoenas nor investigative journalists were needed to find all this out—most of it was publicly revealed by Cambridge Analytica’s chief Alexander Nix in a marketing presentation that received wide distribution on YouTube. Cambridge Analytica (owned partly by Robert Mercer, an early pioneer in artificial intelligence who has been a financial backer of Breitbart News and other right-wing causes) had already done work for the Trump Campaign, and Nix was seeking more business.

The real danger revealed by the Cambridge Analytica scandal is that the information and social platforms of the internet, on which we increasingly spend our time and through which more and more of our personal and social connections flow, are being corrupted in the service of con men, political demagogues and thieves. Russia’s troll farm, the Internet Research Agency, employs fake user accounts to post divisive messages, purchase political ads, spread fabricated images and even organize political rallies.

The danger of misinformation is not just political; it is commercial as well. Major purchasers of internet advertising know that the “pay per click” model is flawed. Competitors can set up bots (or even human campaigns) to click on their ads, driving up their costs and casting doubt on the value of an advertising campaign. The company Devumi sells Twitter followers and retweets to celebrities and businesses in order to make them appear more popular than they are. The followers are fake, cobbled together in automated fashion by scraping the social media web for names and photos.

Until Zuckerberg’s decision to testify before Congress, there was scant evidence that Twitter or Facebook were disturbed about any of this. Still, there are a number of machine learning tools that can be used to identify fake accounts or activity.

Benford's Law

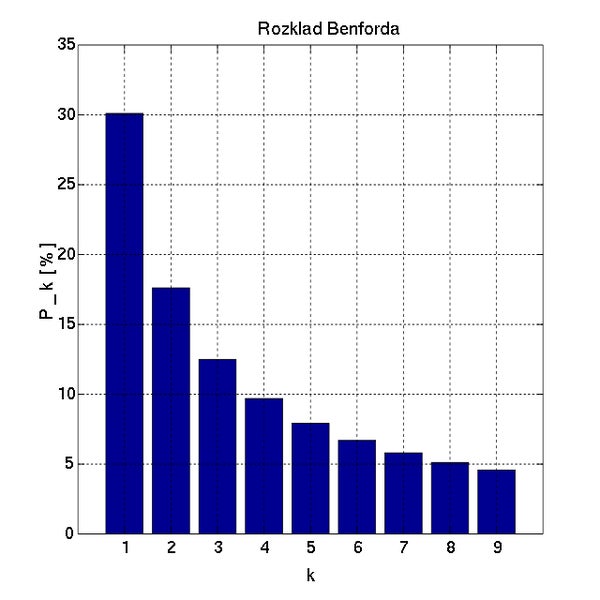

In 2015, a University of Maryland professor, Jen Golbeck, discovered an ingenious real-time method for identifying fake social media accounts. She found that the number of a user’s Twitter or Facebook friends follows a well-known statistical distribution called Benford’s Law. The law states that, in a conforming data set, the first significant digit of numbers is a “1” about 30 percent of the time—six times more often than it’s a 9. The phenomenon, which is quite widespread, is named after physicist Frank Benford, who illustrated it with the surface areas of rivers, street addresses, numbers appearing in a Reader’s Digest issue, and many more examples.

Benford's distribution (Rozklad Benforda in Polish): the percentage of leading digits that are 1s, 2s, etc. Credit: GKnor Wikimedia

In other words, if you looked at (say) a thousand Facebook users and counted how many friends each had, roughly 300 of them would have friend counts in the teens (1x), 100–199 range (1xx) or 1,000–1,999 range (1xxx). Only 5 percent would have counts beginning with a nine: 9, 90–99, 900–999, 9,000–9,999.

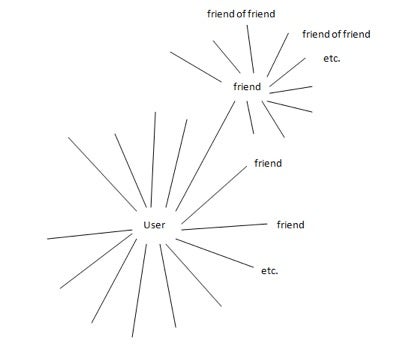

We can represent each Facebook, Twitter or other social media user as a network of linked users. A plot of an individual user’s links to other users might look like the figure below:

To test Benford’s Law, tally the “friends of friends” for each of the user’s friends. Credit: Peter Bruce

To assess whether a user is genuine, we can look at each of that user’s friends, and count their friends or followers. Specifically:

1. Consider a friend or follower of the account in question.

2. Count its followers/friends (“friend of friend”); record.

3. Repeat for all the remaining friends/followers of the original account.

4. Calculate the distribution of those “friend of friend” counts.

Russian Bots Were Revealed, Yet Stayed Online

Golbeck found that the overwhelming majority of Facebook, Twitter and other social media follower and friend counts followed Benford’s Law. On Twitter, however, she found a small set of 170 accounts whose follower distributions differed markedly from that law. In her 2015 paper she wrote:

“Some accounts were spam, but most were part of a network of Russian bots that posted random snippets of literary works or quotations, often pulled arbitrarily from the middle of a sentence. All the Russian accounts behaved the same way: following other accounts of their type, posting exactly one stock photo image, and using a different stock photo image as the profile picture.”

Golbeck told me that she and others posted lists of Russian bots active on Twitter three years ago, and they were still active as of January in this year. Twitter does not seem to care. More to the point, a meticulous cleansing of user records would have the financially deleterious effect of reducing its user base; in Silicon Valley business plans begin and end with a large and constantly growing user base.

Does it matter that fake Russian (and other) Twitter and Facebook accounts and attendant activity persist? What harm can they do?

They can create and distribute false information, which can be put in service of a Cambridge Analytica style psychographic campaign. In Alexander Nix’s presentation of this approach, one of his illustrations showed how alarmist, yet false, messaging highlighting fears of sharks is better than true, but boring, legal notices in keeping people off a private beach. Fake users can help generate the fake content that is needed to serve specific behavior manipulation goals.

They can enable extremists by providing them with a community (albeit a fake one); in the pre-internet age, these extremists would have faced a higher social burden.

They can amplify and boost the impact of pundits and commentators, selected to promote their goals.

They can cause commercial harm and distortions, by boosting products with fake reviews and sabotaging pay-per-click ad campaigns. One speaker at an analytics conference last year estimated that as much as 40 percent of the click activity for which advertisers are paying is fraudulent.

They will, in the long run, taint social media metrics, which is harmful to legitimate nontraditional businesses and organizations that rely on social media to promote their products and services. Fake users tie themselves to legitimate users to boost their own profile, thereby damaging the legitimate users. This blog post has an account of this phenomenon in the music community.

The Future

It is hard to see how government regulation will play a useful role. In today’s digital age, regulation is like placing rocks in a streambed. The water will simply flow around them, even big ones.

It’s possible that the social media titans will use tools at their disposal like those discussed here to drastically reduce the impact of fake accounts and manipulative behavior. Currently, we have the attention of Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, because of the peculiar Cambridge Analytica circumstances, where the storyline runs something like “Breitbart and Trump funder scrapes massive amounts of personal data from Facebook, uses it to manipulate opinion.” Meanwhile, Jack Dorsey, the founder of Twitter, has made some promises to improve identity verification but has otherwise escaped the most recent limelight.

The ultimate solution may lie in a smarter public. Can people be taught to approach what they see on the internet with greater skepticism? P.T. Barnum would say no, but there is one powerful example of public education that had a good and profound end: smoking. The tremendous decline in smoking around the world is due largely to public education and an attendant change in behavior, not to regulation and not to greater public responsibility on the part of tobacco companies.