This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Bernie Sanders is lucky. He needed heart artery stents at the age of 78, but others have had major cardiac issues at younger ages, such as Bob Harper, the fitness guru from The Biggest Loser, who was only 52 when an artery blockage caused him to suffer a heart attack, and he almost died. When it comes to heart disease, you can seem healthy one day and be gone the next. This discrepancy is why doctors and health care professionals work so hard to prevent it: the first warning can often be your last. For those patients who receive preventive cardiac care, many will have some risk factor that their doctor will find and counsel them on how to lower. Even with this precaution, however, 20 percent of heart attacks are still not preventable.

This 20 percent is what I worry about. As a cardiologist who has met too many patients after they needed resuscitation following their heart attack or cardiac arrest, I wanted to do more. I wanted to know what else we are missing, especially for women. When I and my colleagues opened Rush University Medical Center’s Rush Heart Center for Women more than 15 years ago, I needed to learn what young women and men whose fathers or close relatives died or had a heart attack in their 40s were at risk for.

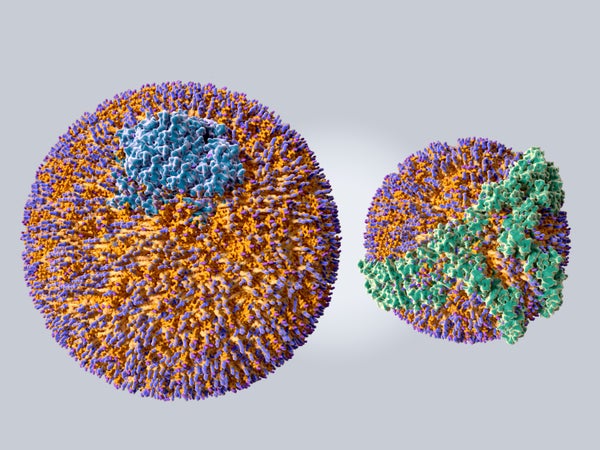

A former mentor of mine, the late Angelo Scanu of the University of Chicago, discovered that a particular cholesterol particle is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease: lipoprotein(a),which is inherited and affects about 20 percent of people. Sometimes called Lp little a or Lp(a), this protein is a complex molecule that is similar to the more familiar low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. They contain similar molecules—apolipoprotein(a), or apo(a), for Lp(A) and apolipoprotein B, or apoB, for LDL. Both can cause plaques in many of the arteries and aortic valve that can lead to heart attacks, strokes or sudden death. And even worse, Lp(a) is similar to the molecule fibrinogen, which causes blood clots.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

So what can one do about Lp(a) when it is found to be elevated in people? Well, that’s the problem. Studies show that plant-based diets can lower Lp(a) by a small percentage, but it may be too small of a difference to be meaningful. Certain individualshave an inherited gene, usually the Lp(a) intron gene, which causes them to have levels so dangerous that even an extremely healthy lifestyle cannot prevent a heart attack. There are some medications that can lower Lp(a), but the currently available ones, such as niacin, which can do so by about 30 percent, don’t actually make a difference in lessening events such as heart attacks or strokes. Underway studies are investigating whether newmedications that can drop Lp(a) by as much as 80 percent will be enough to make a difference in those events. Until those studies are complete, doctors advise that the best way to decrease the risk from Lp(a) is to lower LDL cholesterol and take a small daily dose of aspirin.

Lp(a) is common in the general population, but there are racial differences that may explain why some people are at higher risk of heart disease. South Asians have the highest prevalence, with 35 percent of their population having Lp(a) greater than 50 milligrams per deciliter, followed by Africans at 30 percent. Asians have long been thought by doctors to be at low risk for the illness because East Asians, such as Chinese, Japanese and Koreans, have a lower possibility of experiencing coronary artery disease as compared with other ethnic groups.

But it’s not just South Asians; Filipino and Vietnamese people also have higher risk than the East Asians. Patients from these backgrounds should check with their doctor about the risks they may have for elevated Lp(a).

Alarmingly, the decline in mortality from cardiovascular disease that we saw from about 1980 to 2010 has stopped. Since 2010, the National Center for Health Statistics has reported an increase in cardiovascular-disease-related deaths. In the latest statistical update, from 2016, the leading cause of death from cardiovascular disease remains coronary artery disease, at 43.2 percent, followed by stroke, at 16.9 percent. More than 60 percent of such deaths is still from plaque buildup. Studies are continuing to see if lowering Lp(a) can decrease the risk of heart disease.

Until then, people should calculate their risk of having a cardiac event in the next 10 years. If the risk is greater than, or equal to, 7.5 percent, cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins can reduce the chance of heart attacks strokes and death. If the risk is between 5 percent and 7.5 percent, further tests—including measuring Lp(a), finding coronary artery calcium using CT scans and determining family history of heart disease—may need to be done to decide whether a patient requires statins. Additionally, the Lipoprotein(a) Foundation provides resources for those with inherited Lp(a) to better educate and empower themselves.

When I started my life as a doctor more than 35 years ago, I wanted to become a cardiologist to prevent heart attacks. Those with a family history of early heart disease not only need to get tested for the usual risk factors of high cholesterol, high blood pressure, diabetes and smoking but also must make sure they know if their Lp(a) is high and get their children tested as well.