This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

More than a century and a half after Charles Darwin published his groundbreaking thesis on the development of life, evolution remains a contentious topic in the United States. Most biologists and other scientists contend that evolutionary theory convincingly explains the origins and development of life on Earth. So why are some Americans still arguing about it today?

The answer lies, in large part, in the theological implications of evolutionary thinking. For many religious people, the Darwinian view of life—a panorama of brutal struggle and constant change—may conflict with both the biblical creation story and the Judeo-Christian concept of an active, loving God who intervenes in human events.

A look back at American history shows that, in many ways, questions about evolution have served as proxies in larger debates about religious, ethical and social norms. In particular, religious concerns with evolutionary theory have driven the decades-long opposition to teaching it in public schools. Even within the last 15 years, educators, scientists, parents, religious leaders and others in more than a dozen states have engaged in public battles in school boards, legislatures and courts over how school curricula should handle evolution. These battles have ebbed in recent years, but they have not died out.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The highly charged debates over evolution make it particularly difficult to measure public views on the topic. For this reason, Pew Research Center has experimented with different ways of asking survey questions about evolution and has studied how these variations affect the public’s responses.

Recently, the center conducted a survey in which respondents were randomly assigned to be asked about evolution in one of two ways.

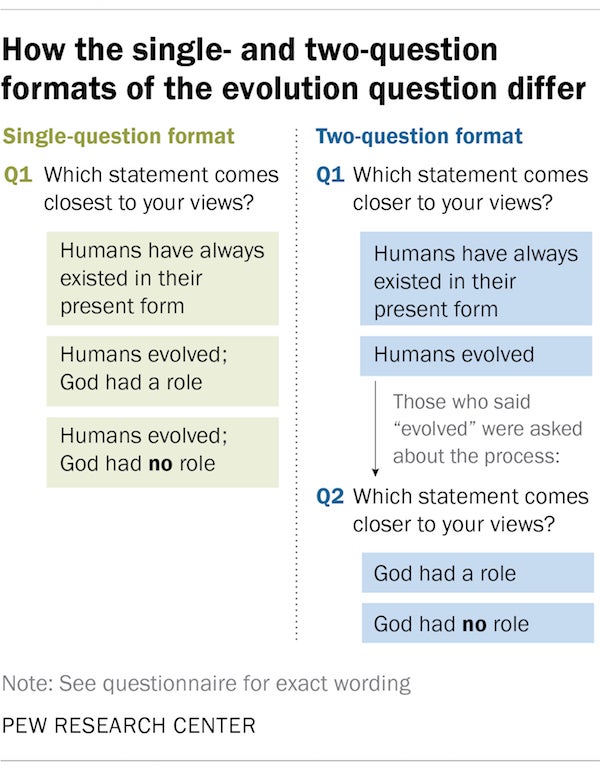

Half of the respondents were asked for their views using a two-question “branched choice” format. First, they were asked whether they believe that humans have always existed in their present form, or that humans have evolved over time. Then, those who said humans have evolved were branched to a second question, asking whether they believe that evolution occurred in a process guided or allowed by God, or that evolution occurred through processes like natural selection without involvement from God.

The other half of respondents were asked a single question about their views on evolution and given three response options: “Humans have evolved over time due to processes such as natural selection; God or a higher power had no role in this process”; “Humans have evolved over time due to processes that were guided or allowed by God or a higher power”; or “Humans have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.”

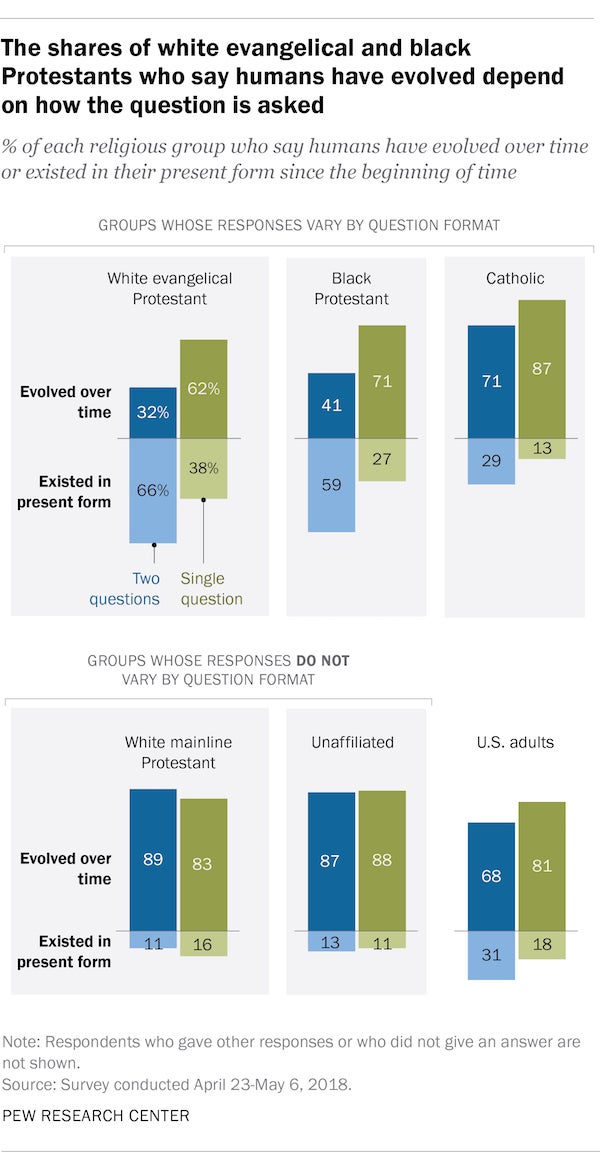

Overall, the percentage of Americans who take the “creationist” position is lower in the single-question format (when survey respondents are given an immediate option to express both acceptance of evolution and belief that God or a higher power had a role in such processes) than in the two-question format. When asked the single-question version, just 18 percent of U.S adults say humans have always existed in their present form, while 81 percent say humans have evolved over time. By contrast, in the two-question approach, nearly one third of respondents (31 percent) say humans have always existed in their present form, and 68 percent say they evolved over time. These results suggest that some Americans who do accept that humans have evolved are reluctant to say so in the two-question approach, perhaps because they are uncomfortable placing themselves on the secular side of a cultural divide.

The effect of the different question formats is especially pronounced among two of the most religious subsets of U.S. Christians: white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants. When asked using the two-question format, about two thirds of white evangelical Protestants (66 percent) take a “creationist” stance, saying that “humans have always existed in their present form since the beginning of time.” But when asked about human evolution in a single-question format, a 62 percent majority of white evangelical Protestants take the position that humans have evolved over time.

Similarly, 59 percent of black Protestants who were asked about this topic in the two-question format say humans have always existed in their present form. By contrast, with the single-question format, just 27 percent of black Protestants take the “creationist” position, while a 71 percent majority say humans have evolved over time.

These findings are in keeping with arguments by sociologists of religion that highly religious Americans may feel conflicted about saying humans have evolved, unless they are able to clarify that they also believe God had a hand in the development of life. Indeed, the subset of people who respond differently to the two survey approaches consists mainly of those who believe that God or a higher power played a role in human evolution. For example, nearly all white evangelical Protestants who say humans have evolved—whether in a branched-choice or single-question format—also say God had a role in human evolution.

There are smaller differences among Catholics in response to the two different question formats, and white mainline Protestants express roughly the same views about evolution regardless of the approach used. Overwhelming majorities of the religiously unaffiliated (those who describe their religion as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular) say humans have evolved over time on both the two-question (87 percent) and the single-question format (88 percent).

Prior to this recent experiment, the center tested various versions of a two-step approach to asking about evolution. In one line of testing, we varied the survey context (that is, the questions that immediately precede the evolution questions) but found no differences in survey responses. In another line of testing, we varied whether the questions asked about the evolution of “humans and other living things” or “animals and other living things” and, again, found no differences in opinion about evolution among the U.S. population as a whole.

Considered together, the experiments illustrate the importance of testing multiple ways of asking about evolution. For some people, views about the origins and development of human life are bound up with deeply held religious beliefs. Pew Research Center’s goal in designing questions on this topic is to allow respondents to share their thoughts about both the scientific theory of evolution and whether God played a role in the creation and development of life on Earth—and to do so in a way that does not force respondents to choose between science and religion. Indeed, the data show that a sizable share of Americans believe both that life on Earth has evolved over time and that God played some role in the evolutionary process.