This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Look at the picture above. Do you think the young womanis surprised? You may be wrong. A facial expression of emotion depends not only on the face itself, but also the context in which the expression is situated.

We all remember “the dress.” An illusion like this shows that even a phenomenon as basic as color perception can be ambiguous. Emotions are much more complex entities than colors and thus can lead to even more confusion. Our perception of emotional expressions is related not only to the physical properties of a face, but also to a bunch of other factors affecting both the percipient (for example, a person's past experience, cultural background, or individual expectations) and the situation itself (the context).

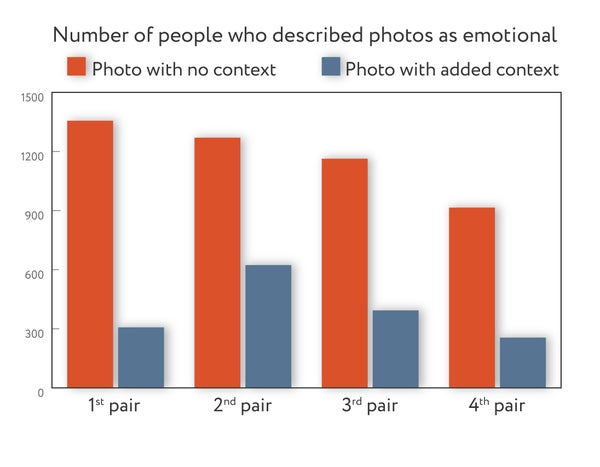

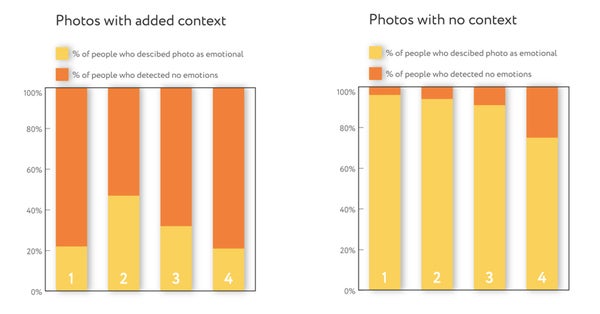

To test that idea, researchers at Neurodata Lab created a short test and asked more than 1,400 people from 29 countries to have a look at four pairs of photographs, or eight in total. The first image in each pair showed a woman with a certain facial expression. The second was identical to the first, except that it had an object added to it: a mascara brush, a book and glasses, a toothpick or a guitar. These objects added context. People then had to look at every image and indicate if the facial expressions looked emotional to them.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit: Neurodata Lab, LLC.

Responses differed significantly between the photos with an added object and those without one. On average, people responded that the faces were “emotional” in most images without any additional context (in 3.52 out of four). After an object was added, subjects frequently changed their opinions and instead responded that emotions were present in only one about photo out of four (to be precise, it was 1.2 out of four).

In other words, the results suggest that in more than 60 percent of cases, the addition of objects changed how people perceived emotional expressions in the photos.

Credit: Neurodata Lab, LLC

Credit: Neurodata Lab, LLC

Why Is the Difference So Salient?

Emotional perception depends on context in the broadest sense of this word. The way we express ourselves nonverbally is affected by an array of factors, such as individual differences in age, gender, society or culture, and differences in various situational factors.

It is natural for humans to seek a universal formula, a one-size-fits-all explanation for what is happening around them. Emotions are no exception, and in the 1970s, American psychologist Paul Ekman introduced his concept of universality of emotions, stating that all humans, everywhere, experienced six basic ones, and that they expressed them in the same way.

But in a study published in a few years ago, psychologist Carlos Crivelli, then at the Autonomous University of Madrid, decided to question and test the Western concept of emotions. He traveled to the Trobriand Islands, a remote archipelago in Papua New Guinea. There, he found isolated societies living in traditional settlements. During field experiments, he discovered that an expression Westerners commonly associate with fear was used by the Trobriand people as a threatening display. Living on isolated islands with a limited contact with the outside world had a strong impact on the ways the Trobriand people experienced emotions; and the way they perceived some emotional facial expressions did not seem to fit into Ekman’s simple model.

“Social reality is not just about words—it gets under your skin. If you perceive the same baked good as a decadent ‘'cupcake'’ or a healthful ‘muffin,'’ research suggests that your body metabolizes it differently,” wrote psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett in her book How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain. “Likewise, the words and concepts of your culture help to shape your brain wiring and your physical changes during emotion.”

Cultural background is not the only factor creating noticeable differences in perception—there are much more subtle, peculiar, and individual influences as well. For example, children are slower and less accurate in recognizing facial expressions of emotions than both adolescents and adults.

Fernando Ferreira-Santos, of the Laboratory of Neuropsychophysiology at the University of Porto in Portugal, has been researching age differences in emotional perception. He studies whether there is a correlation between age and the ability to identify emotional expressions.

“The link between mental states and facial expressions is virtually never a one-to-one relationship,” Ferreira-Santos says. “A given mental state—for example, an emotional state—can be associated with different behaviors, while a single behavior may come about during different mental states. Facial movements are not different, and thus, the same facial signal may have different meanings.”

So perceiving emotions is more than recognizing the category, such as fear or anger, to which certain facial movements belong. The way children learn how to label emotional expressions is instructive: They begin by differentiating the valence of facial displays, distinguishing between good and bad expressions, and only gradually develop the adult-like categories of "fear," "sadness" and so on. “Сhildren learn the stereotypical facial ‘'expressions'’ of their culture,” Ferreira-Santos says.

Kristen Lindquist, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, agrees: “Most of the data,” she says, “suggest that people differ in their ability to perceive emotion on faces because of learning.,” she says. “The information on a face is ambiguous, and people differ in the extent to which they use the context and prior learning to disambiguate that information. This explains why children become more adept at understanding others' facial expressions with age, and why some people are very socially astute whereas others are not.”

Emotions in Machines and Humans: What Do We Have in Common?

The world of emotional experiences provides us with important information about a person. For a number of reasons, it has been long ignored in the field of AI. Traditionally, AI has been associated with rational thinking, the ability to solve problems and perform complex logical operations. However, emotions are an important and integral part of our life, which is why, smart algorithms today are learning to understand our emotional states and correctly react to them. And, perhaps, the task of correctly perceiving human emotions and expressing feelings is a much more difficult operation for an AI than playing chess.

The small test described above shows that everything is ambiguous when it comes to emotional expressions. Emotion-analyzing algorithms should be much more complex than they are now. In emotion analysis, any instance of an audio or video fragment is meticulously divided and taken as a series of separate frames frozen in time. When taken out of a natural course of events, emotion recognition can become a real challenge. It is no wonder that recognition of mixed, fake or hidden emotions would require contextual information, but the task of understanding such context is still a difficult one for computers.

“In general, nonverbal cues—facial expressions, tone of voice, gestures—tend to convey meaning in a more flexible way than words,” says Alessandro Vinciarelli, of the University of Glasgow, whose main research interest lies in teaching social communication to artificial intelligence. “This is one of the main reasons why nonverbal communication is such a powerful means to convey subtle nuances, especially when it comes to social and emotional aspects of interaction. However, this comes at the cost of ambiguity and uncertainty that can be dealt with only by taking context into account.”

In machine learning, the notion of context has two main forms: The first is related to what is called a “multimodal approach” to automated emotion recognition, in which channels—for example, facial expressions and gestures—act as context for each other

“It has been shown that the combination of channels leads to some possible effects.,” Vinciarelli explains. “This has made it easier to develop technological approaches that benefit from the joint analysis of multiple cues. The probability of a technology misinterpreting several cues is smaller than the probability of misinterpreting each one of them individually. This leads to better accuracy in emotion recognition.”

The second type of context is more familiar: the identification of relevant features in the a particular situation in which the communication takes place. It is also one of the difficult tasks for AIs.

“Here, no clear model or principle to context analysis has been identified,” Vinciarelli says. “Technology has been unable to identify measurable features that can describe a situation. Even the most successful attempt—called W5 because it includes when, why, where, what and whom—did not lead to satisfactory results. And the successful waves of context-aware technologies presented in the past decades have not left major traces."

“However,” he adds, “the diffusion of wearable sensors and mobile phones has now made it possible to capture unprecedentedly large amounts of data about the environment in which every person is located. This can possibly be the key towards the development of technologies more capable to be context-dependent.”