This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Well, it's Groundhog Day…again. And Bill Murray is still right. For many people today wanting a prediction about the weather, you're asking the wrong Phil, or the wrong genus, anyway. Folklore aside, there's little basis for believing groundhogs such as Punxsutawney Phil are particularly well equipped for forecasting the rest of the winter. Their pre-vernal activity indicates a regular hibernation pattern that begins and ends, more or less, about the same time every year. In Pennsylvania, home of the world's most famous marmot, they emerge around February 2, interested more in claiming territory, cleaning out their burrows, and preparing for mating than in the climatic curiosity of their human neighbors.

Birds, on the other hand, have a rich (and perhaps more accurate) history of predicting future weather conditions, in proverbs such as “Hawks flying high means a clear sky. When they fly low, prepare for a blow.” Bird behavior prior to a marked shift in atmospheric conditions suggests they perceive pending weather changes. And recent research has revealed that birds sense changes in barometric pressure, sometimes days in advance of a pending storm.

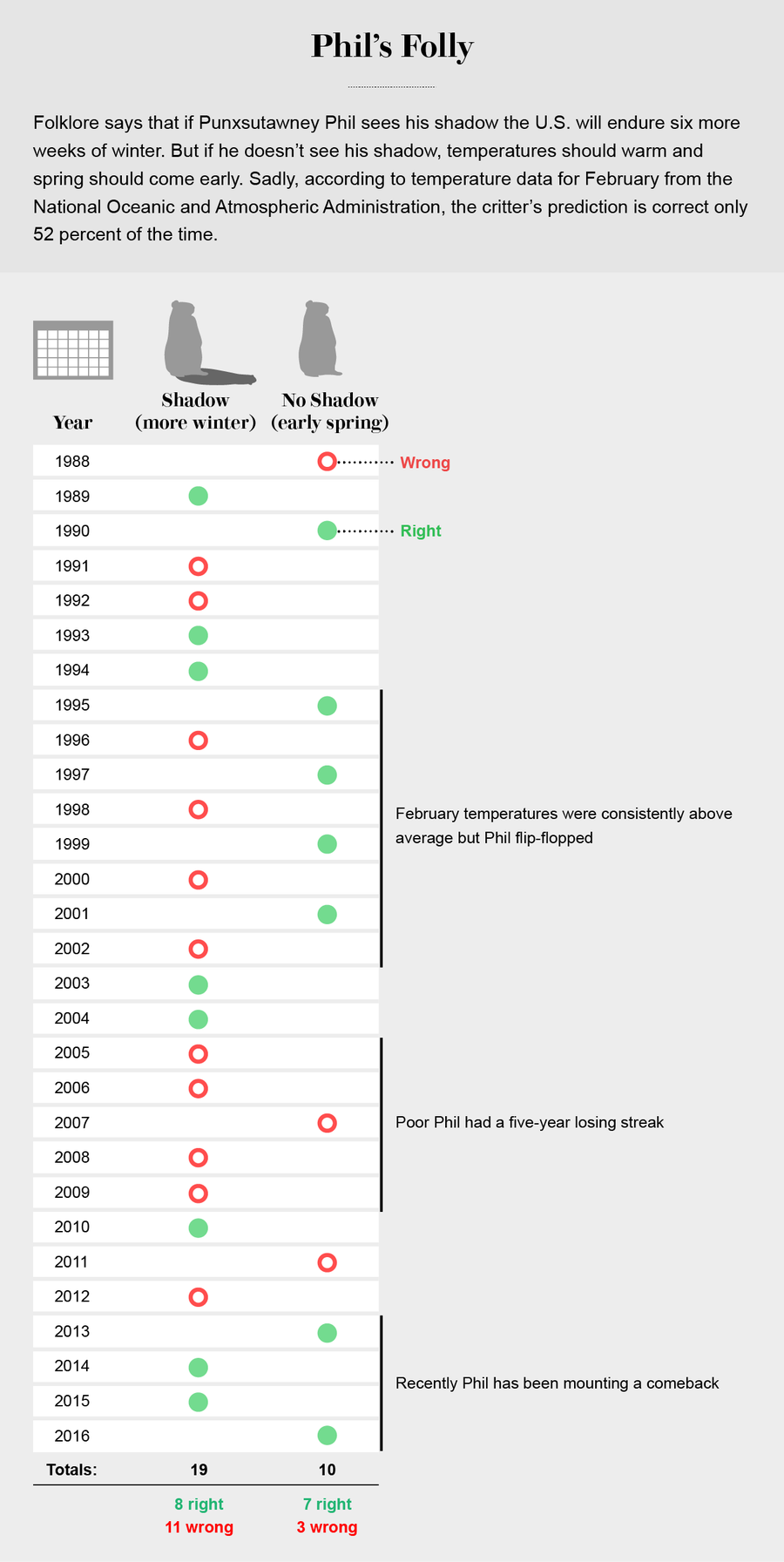

As remarkable as the sense of birds might be, these proverbs reflect short-term change in weather. The appeal of Punxsutawney Phil is the hope that his behavior in early February can give us insight into future weather up to six weeks in advance; he appears to do no better than a coin flip.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Migratory bird behavior during winter may predict better the upcoming weather. At its most simple, many species of migratory birds face a trade-off between moving far enough south for a mild winter and staying as far north as possible to “get a jump” on returning to the breeding grounds and maximizing chances for acquiring a territory and a mate.

Eastern bluebirds, a great example of this trade-off, breed early in spring, are nest-site–limited, and defend an exclusive breeding territory—a major advantage to individuals who arrive early to breed. But wintering too far north puts individuals at risk of severe weather. Evidence that bluebirds make winter adjustments comes from observations by birders through the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology’s citizen science website eBird.org. When I mapped birders’ sightings, I found bluebirds went farther north in warmer winters, while in other years the wintering bluebirds were found farther south.

Credit: Amanda Montañez. Source: NOAA

Of course, bluebirds don’t thumb through the Farmers’ Almanac in November to know which classifieds will have their winter home. Their evolutionary behavior is environmental-cue–sensed in early or mid-winter, correlated with winter’s harshness later in the season. For a given winter, birds that settle in the “right” location (not too far north or south), and adjust as needed, appear the most successful. This strong natural selection on winter habitat choice provides an important advantage to birds that have the genetic and/or cognitive makeup to use predictive cues compared to those using the wrong cue or using it incorrectly.

Evidence is mounting that plants and animals are remarkable integrators of weather and climate. For example, as climate is warming, earlier springs are marked by earlier burst of tree buds and earlier arrival of a range of bird species. We note early changes in timing not just through smartphone apps, such as eBird, but also through the carefully written observations of nature enthusiasts the last 100 years. People noting the first buds, flowers and birds in their yards have contributed critical information to help us understand how a changing climate will affect the world around us.

As our weather becomes more variable and extreme—longer droughts, colder cold spells, stronger storms—we should worry for the humble bluebird that in a warming and more variable climate, the correlation between the cue and the outcome might break. In the short-term, Eastern bluebirds might adapt, they might shift to different cues or use the old cue slightly differently. But, if the climate changes too quickly or in unpredictable ways, then Eastern bluebirds might follow other species into decline. Such a concern makes clear the important value of citizen science data in helping us learn from our feathered friends whether the early bird still gets…the territory.