This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

For almost half my life, I have played the sport of ultimate—previously called ultimate Frisbee—across several states and even internationally, in all types of conditions. On one extreme, the snowy outdoor February tournament in New Hampshire called Live Freeze or Die takes pride in the toughness of its competitors (the name is a takeoff on the state motto,“Live Free or Die”). On the other end, tournaments in the Southwest on scorching turf fields have made me think my feet were melting.

Ultimate only requires one piece of equipment—the disc (not “the Frisbee,” which is the trademarked name of the disc made by Wham-O). Players, like me, have noticed that discs fly differently depending on the temperature. In the cold, discs are rigid, painful to catch and break easily. Discs left out in a hot car are floppy and don’t fly as well.

For nearly three decades, one company, Discraft, has dominated the disc market. But recently, a small enterprise developed a new disc that’s now edging for a spot on the field.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Zahlen Titcomb and his four siblings, founders of the ultimate apparel company Five Ultimate, have thrown and caught discs countless times. Recognizing that players would appreciate a disc that performs better across a wide range of temperatures, they decided to improve the disc on their own.

They also wanted to create a long-lasting disc. Discs may gain dents over use, adding wobbles to their flights.

Newly produced ARIA discs are ready for quality control checks. Credit: ARIA Ultimate

The problem, however, was the Titcombs didn’t know anything about designing a disc. So they started with intuitions of how a disc should feel and perform and progressed with trial and error.

To mass produce a disc, the Titcombs would eventually need a disc mold. Hence, they first experimented with the disc shape. They adhered to the size and weight requirements for official competition approval. They used computer-aided design software and 3D printing to develop different versions. They threw each iteration, advancing toward one with the weight distribution and “rim feel” they preferred.

Next, they focused on the materials. Companies won’t reveal their trade secrets, so the five siblings started from scratch. In their initial experiments, they gathered old discs and put them in the freezer and oven to compare how they performed, such as testing how much a disc would bend and return to its original shape. They even looked at other durable products, including dog toys.

Then, they brought the products with properties they liked to engineer friends with access to tools like Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy to try learning more about the materials. FTIR collects a chemical ‘fingerprint’ of the sample after hitting it with infrared radiation. The radiation passes through or is absorbed by the sample, in a unique way depending on the compounds. This tool helped the team find the general classes of materials used in the products they liked, but it didn’t reveal everything.

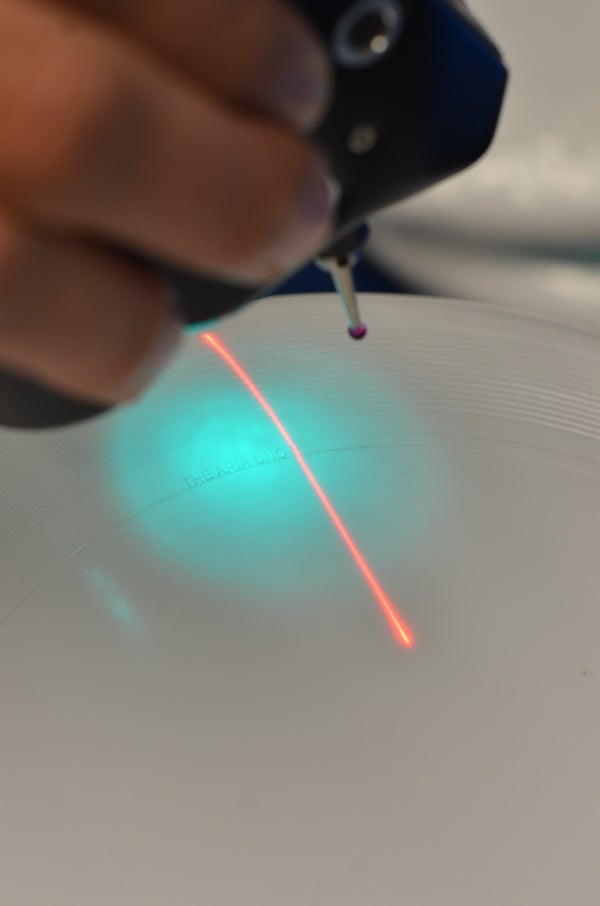

The disc developers use digital modeling software to test for micro-discrepancies in the rim angles of the prototypes. Credit: ARIA Ultimate

“It’s like trying to unbake chocolate chip cookies,” explains Titcomb. “You’re never going to figure out what brands of chocolate you started with or how much of this or that flour or whether it was brown sugar or organic brown sugar.”

I was curious what these ingredients are, so I reached out to a research professor at Dartmouth University. Rachel Obbard teaches a course on materials in sports equipment. Plastic objects like discs are usually made of a polymer called polyethylene, she says. Additives may include brighteners for coloring, release agents to help remove the item from the mold and ultraviolet protection.

Finally, the designers considered the disc’s aesthetics. One source of materials created a disc that appears pockmarked. The disc performed well, but its appearance might turn off the community. Instead, they went for a clean white look.

Two years and 67 prototypes later, Titcomb and his team had a version that worked. They found a combination of fewer, high-quality materials that were crucial for their desired results. Titcomb believes the disc improvements will “allow more people to play in more conditions with a more regular standardized feel and flight path.”

I wanted to see how it feels to throw the ARIA disc, so I brought one to my Tuesday night league game in Sunnyvale, California. It was a windless night around 50 degrees, slightly chilly but far from the coldest temperatures I have played in. To warm up, I practiced throwing and catching. It felt like other discs that haven’t been thrown before—it flew how I wanted it to.

My throwing partner was Albert Wu, a veteran player of more than 20 years. He actually didn’t notice it was a different brand of disc. When I told him afterwards, he was “pleasantly surprised” it was not his normal disc.

And maybe that’s the point. The Titcombs want the new disc to feel natural to ultimate players.

Top athletes braved winds and cold rain for the ARIA Ultimate Game of the Year 2017 in Seattle. Credit: ARIA Ultimate

Wu, who considers himself a Discraft purist, is not sure he would change to the ARIA disc but noted: “I think if I played with it, I enjoyed it and I couldn’t really tell the difference and if it actually played better in cold and hot, I might consider switching over.”

I personally look forward to testing its performance in hotter and colder conditions.

In August, the ARIA disc received official approval by the governing national organization, USA Ultimate. It met the size and weight requirements and passed the multilevel player review that tested the flight characteristics.

The timing for this new enterprise couldn’t be better. As American youths shy away from the traditional sports such as football and baseball, their participation in non-mainstream sports like ultimate increases. Given ultimate’s expansion around the world, the International Olympic Committee is considering adding it to the Summer Olympic Games, as early as 2024.

The disc has transformed significantly from its early days as an inverted pie tin. Perhaps the ARIA disc represents the next stage in the disc’s flight throughout history.