This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The top of the sky darkened to a deep purple-blue, leaving a glow of pink on the horizon and an odd feeling of stillness as dozens of spectators cheered. A seemingly alien object—a pitch-black circle surrounded by shimmering tendrils—replaced the sun. This was it: totality of the eclipse. It was nature’s gift to those who put in the effort to experience two-minutes-and-change of ecstasy.

To get myself properly stationed in Madras, Oregon for this brief delight, I began planning logistics nine months in advance—including contingencies for soul-crushing hurdles such as traffic and clouds. While anxiety and devastation raised the collective American blood pressure level in the pre-eclipse months of 2017—uncertainties in international relations, domestic political tensions, talk of nuclear conflict, more evidence of climate change, and severe weather like Hurricane Harvey pounding Texas, to name just a few—I kept my spirits up with the mantra, “I just have to make it to Madras by August 21.”

That was not the only scheduled short-duration, high-impact feast for the senses this year. A traveling exhibit called Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors by acclaimed Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama treated crowds in Washington, Seattle and Los Angeles to 30-second blissful dips into a series of small mirrored rooms. Both the eclipse, which I saw once, and the exhibit, which I saw twice, shared the odd quality of requiring far more time to plan and wait than the duration of the event itself.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

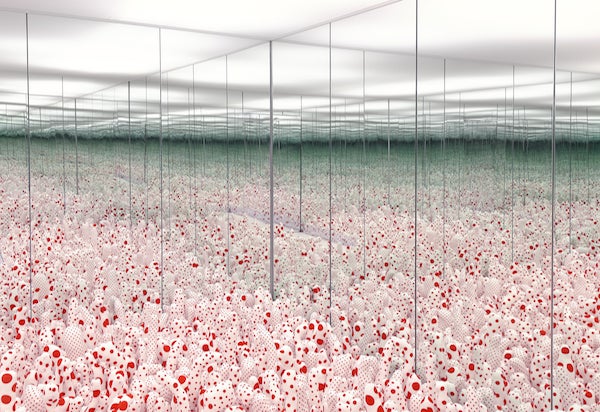

Yayoi Kusama: Installation view of Infinity Mirror Room—Phalli’s Field, 1965, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Credit: Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore; Victoria Miro, London; David Zwirner, New York. © Yayoi Kusama. Photo by Cathy Carver

Besides being some of the most wondrous, awe-inspiring experiences of the year, they both spoke to desperate urges I have had to transcend Earthly chaos—both in the world at large and in my personal life this year. I think part of the reason the eclipse and Kusama exhibit were so implausibly enchanting was they put me in a mindset where every second had to count, so my attention was clearly focused. “One really felt one had to be urgently transcendent—to be, as it were, transcendent quickly and with all one’s might,” says David Landy, assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences at Indiana University in Bloomington. Though superficially different, both experiences were special because they allowed me to forget worldly and personal troubles, forge new bonds with friends and form memories that I return to when times get tough.

When we think about how good or bad an experience is, does it matter how long it lasts? Research in the early 1990s by Nobel prize–winning economist Daniel Kahneman, professor emeritus at Princeton University, and colleagues suggested the answer is no—that our evaluations of pain and pleasure have “duration neglect.” Instead, says Thomas Gilovich at Cornell, we more strongly judge an experience based on two things: the most positive or negative moment, and what the end of it was like. Scientists call this the “peak-end rule.”

“With respect to happiness in particular, Amit Kumar and I have work showing how much those assessments are tied to the stories we tell about our experiences, and duration does not matter a great deal for what makes a good story,” Gilovich told me by email.

In “Living and Thinking About It: Two Perspectives on Life,” Kahneman and co-author Jason Riis wrote, “An individual's life could be described—at impractical length—as a string of moments. A common estimate is that each of these moments of psychological present may last up to three seconds, suggesting that people experience some 20 000 moments in a waking day, and upwards of 500 million moments in a 70-year life.” That would mean that a stint in a Kusama mirror room would be about 10 moments, while the eclipse’s totality consisted of a little over 40—so, relatively few to choose from as a “peak,” when you think about it. But these brief bursts of wonder formed the backbone to the story of my year.

February: Infinity Mirrors

I happened to be in Washington, D.C. in February when the Kusama exhibit opened at the Hirshhorn Museum—its world premiere. Nearly 160,000 people visited the D.C. installation, according to the Smithsonian Institution, before it moved on to dazzle Seattle and then Los Angeles. It was an unusually warm winter day, and I was full of energy and curiosity.

Yayoi Kusama: Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity, 2009, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Collection of the artist. Credit: Courtesy of Ota Fine Arts, Tokyo/Singapore; Victoria Miro, London; David Zwirner, New York. © Yayoi Kusama. Photo by Cathy Carver

What happens in a timed infinity room? Imagine stepping into a large box with mirrored panels inside and a bunch of other objects, and then the door closes. Because of the mirror-reflecting-mirror effect, it appears as though you are surrounded by infinitely many of those things—multicolored lights or phallic-shaped protrusions with red spots, for example.

When I entered the special exhibit area in D.C., a museum docent explained the lines for rooms were up to an hour long (in practice, it was more like 30 to 45 minutes). Each person had about 30 seconds per room—and those of us who came alone shared these visions with strangers. I had not blocked out enough time for so many queues, so I saw four of the six main installations. Like everyone else addicted to validation on social media, I unfortunately spent a lot of the time taking pictures to post afterward—just as I would later do during the eclipse.

The mirrored room in which I felt I truly lost myself, and did not want to leave, was called Aftermath of Obliteration and Eternity. This room is totally dark save for glowing orange-yellow lanterns, flickering and seemingly hanging everywhere—even above and below you. I shared the room with an older couple, but we were all silent in our awe. The sense of peace and wonder in that room was potent enough, even in the 30 seconds or so, that I still remember it many months later.

“Kusama’s goal, in this project, can be described as creating otherwise inaccessible experiences of the boundless and huge. It’s not infinite, of course, because your body necessarily blocks the infinite regress at some point, and because of limitations of your visual system—but it’s a much larger experience of expansive repetition than can be readily created in any other way,” Landy says. “The solar eclipse, of course, does the same thing, both by focusing your attention on the sun and orbital paths of the Earth and moon, and also simply by refreshing your attention on the more mundane hugeness of the daytime sky.”

August: The Eclipse

The moon’s passage in front of the sun on August 21 piqued my interest not only for its astronomical significance, but also because so many people made an effort to take part. About 154 million Americans directly watched the solar eclipse, with about 20 million of them traveling to see it, according to a University of Michigan study under a cooperative agreement with NASA (disclosure: I am employed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory). After some cursory research on weather patterns and transit options, I decided I wanted to view the eclipse from a little place in Oregon called Madras. By summer, predictions loomed that this town of 6,000 would see about 100,000 eclipse visitors.

I remember warning my friends about possible apocalyptic traffic nightmares on the roads toward Madras, grabbing some of the last jugs of water on otherwise empty shelves at a Portland grocery store, hoarding certified solar viewing glasses, memorizing rural highway routes. Yet we all got to Madras in time: my cousin, two friends from Los Angeles, one friend from Atlanta and two of my cousin’s friends, all together in a field behind the overpriced motel I had booked nine months in advance.

Around the time that the sun had evolved into a crescent—a dull orange through our eclipse glasses—I started noticing a drop in temperature. Not only that, but I felt almost lightheaded, unsure how to process the general dimness accompanied by the glow of my friends’ faces. With a feeling I can only describe as “high,” I exclaimed, “It’s really happening!”

In thinking about the eclipse with respect to the peak-end rule, “the peak would be whatever moment was most moving/exhilarating and the end would be the moment just before the sun returned to its usual, completely unobstructed state,” Gilovich says. For me, the peak was probably seeing the blotted-out sun for the first time, after granting myself several seconds to look around—marveling at all the colors of the sky and the brightness of a planet revealed in the dark blue overhead (it was Venus). Then, all too soon, came the grand finale. A “diamond” emerged on the ring around the blackness, peeking out like a tiny fireball, signaling that totality was over. Indeed, it was a spectacular end—but so was reflecting on it with my friends afterward, or “social coordination,” as behavioral economist Dan Ariely at Duke calls it. “Doing something together at the same time creates this common issue to talk about,” he says.

December: Infinity Mirrors, Take 2

For weeks after the eclipse, any time I wanted to relax or calm myself, I would envision what the sun looked like during totality. The image was unlike any photo I had seen—it was mine alone, glimmering in my mind’s eye. But in early December, my new, exciting relationship suddenly ended in heartbreak, and not even memories of the eclipse could ease my pain.

Knowing I was shattered, a good friend woke up early on a Friday to get us standby tickets to Infinity Mirrors at L.A.’s Broad Museum. Both the exhibit and the eclipse had an element of uncertainty: clouds would have ruined the celestial show, and standby lines at the Broad can go for hours. But my friend got lucky and snagged the tickets after a little over an hour. She had not seen the exhibit before, and I really wanted to experience it again without taking so many photos. More than ever in 2017, I needed an escape.

The idea of a series of visually explosive rooms, where social media addicts snap pictures galore, has really taken off—in Los Angeles we now have 29Rooms, an “interactive funhouse of style, culture, & technology,” as well as Happy Place and the Museum of Ice Cream. They all seem to provide unique environments for fun photos, rather than focusing on “you now have less than a minute to experience infinity”—and my favorite part of 29Rooms was a music lounge room called “Dreamer’s Den,” which was more of an intimate concert than a photo op.

Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrored Room – The Souls of Millions of Light Years Away, 2013, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden Credit: Courtesy of David Zwirner, N.Y. © Yayoi Kusama. Photo by Cathy Carver

The first few rooms of my second Kusama visit were beautiful—but they meant something different this time. Whereas in February I walked through the exhibit for the first time and alone, in L.A. I knew what to expect, but got to share it with a close friend. We discussed our impressions after we lost ourselves together in the field of spotted stuffed tubes and the large pink beach balls. Those flickering, otherworldly golden lanterns once again seemed to transport my spirit, even in only 30 seconds. And because of a series of events involving a fire alarm, the docents gave us two coveted 30-second dips in the room of black-spotted yellow pumpkins. I was so thankful for the prohibition on photography in this room—free of the fear of missing a good Instagram, we delighted in 360 degrees of glowing pumpkins.

The end of the exhibit—the Obliteration Room—is not timed, so my friend and I leisurely examined every detail we could. The whole design relies on audience participation: each visitor receives a sheet of colored circular stickers and puts them wherever he or she would like—on furniture, on the floor, on the walls, you name it. The “living room” and “dining room” sets begin totally white at the beginning of the exhibit’s run, but over time they become bathed in color. About 750,000 stickers were stuck in this room during the Washington run, making it look as though it had been splatter-painted.

Yayoi Kusama: The Obliteration Room, 2002 to present. Collaboration between Yayoi Kusama and Queensland Art Gallery. Gift of the artist through the Queensland Art Gallery Foundation 2012. Collection: Queensland Art Gallery, Brisbane, Australia. Photograph: QAGOMA Photography. © Yayoi Kusama

As I affixed a yellow circle to the armchair in the Los Angeles installation, I felt it—the amazement of contributing to this collective artwork, making my small mark on a masterpiece that evolved each time someone made a decision about where to place a circle. For a moment, I let go of my personal woes and connected with all of the exhibit-goers of the past and future, each of us making a small choice that, over time, would influence the greater whole, even if it was not apparent at the time. It felt analogous to seeing the glimmer in the eyes of everyone I have encountered who saw the 2017 eclipse—each with a personal appreciation, a story and a hopeful plan to go to South America for the next one.

Psychologists often talk about “flashbulb memories,” which carry more visceral reactions and vivid recollection (though sometimes inaccurate) than everyday memories, in the context of unexpected tragedies, such as the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and other large-scale bad news. Those of us who saw the eclipse and the Kusama exhibit, by contrast, carefully planned and waited—but both undoubtedly generated powerful, emotional memories. Appropriate to the word “flashbulb,” both were plays on light and the absence of thereof.

In a flash, they were gone. But in distressing times, memories of them are the most readily available transcendence.