This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

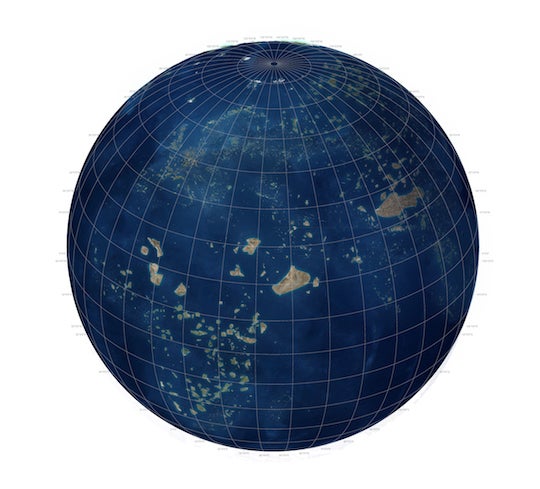

Seen from 28,000 miles away, Earth is beautiful. But its beauty is deceptive. We don’t see the five billion tons of surplus carbon we pump into the atmosphere every year, our toxic waterways or our sprawling megacities and the vast fossil-fueled monocultures of cattle and corn that feed them. Most importantly, we don’t see the global archipelago of protected areas into which the world’s genetic biodiversity is now huddled. On the eve of Earth Day 2017 we launched a new atlas dedicated to examining this archipelago in detail. It’s called the Atlas for the End of the World.

What’s left of the world’s biodiversity in protected areas. Credit: Richard Weller

The first atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (The Theater of the World), was published in 1570 by the famous book collector and engraver from Antwerp, Abraham Ortelius. With his maps Ortelius laid bare a world of healthy—we can now say “Holocene”—eco-regions ripe for colonization and exploitation. Lauded for its accuracy, the Theatrum quickly became a best seller.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Despite its apocalyptic title, our new Atlas is not about the end of the world per se; it is about the end of Ortelius’s world, the end of the world as a God-given and unlimited resource for human exploitation and its concomitant myths of progress. On this, even the Catholic Church is now clear: “We have no such right,” Pope Francis says.

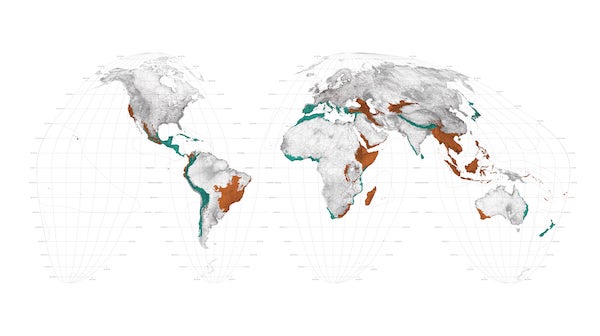

At face value, atlases are just books of maps. The maps in the Atlas for the End of the World are, however, quite specific. They specifically show the difference between the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) targets for achieving 17 percent (global terrestrial) protected area by 2020 and what is actually today protected in the 398 eco-regions that comprise the world’s 36 biodiversity hotspots.

The so-called hotspots are regions agreed on by the scientific and conservation communities as the most important and the most threatened biological places on Earth. They are also places of exceptional linguistic diversity, much of which is also predicted to disappear by century’s end—suggesting, perhaps, that the fates of nature and culture are one and the same. Many of the hotspots are also bedeviled by poverty, violence and corruption.

The world’s biodiversity hotspots. The green areas have met United Nation’s targets of protecting 17 percent of their total area; the orange areas have not. Credit: Richard Weller

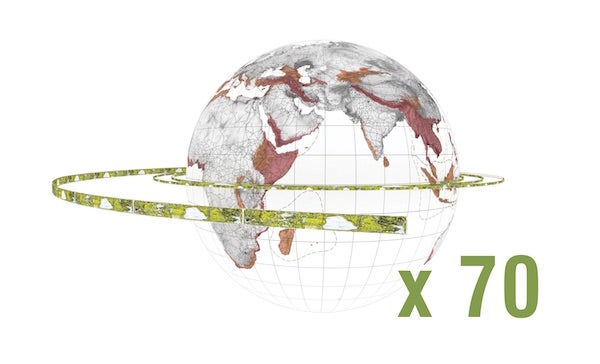

When my research assistants and I began this mapping project in 2013, the world’s total terrestrial protected area was hovering at 13.5 percent. Recent figures (2015 data) suggest a total of 15.4 percent. That’s 20.6 million square kilometers of land distributed across more than 209,000 sites in 235 different countries. So, with 15.4 percent already secured, only an additional 1.6 percent protected area is needed to satisfy the Convention’s 2020 target. This amount might seem paltry, but 1.6 percent of Earth’s terrestrial surface is 2.3 million square kilometers, the equivalent of nearly 700,000 Central Parks. That’s a Central Park stretching 70 times around the world! The research question we asked was where exactly should this additional protected land be?

To meet UN protected area targets over 700,000 Central Parks need to be added to the world’s protected area estate. Credit: Richard Weller

According to the CBD, we can’t just fence off 1.6 percent of Siberia or some other place and then say we’re done! The crucial words in the small print of the CBD are that the global protected estate must be “representative” and “connected.” In theory, this means 17 percent of each of the world’s 867 eco-regions should be protected and connected.

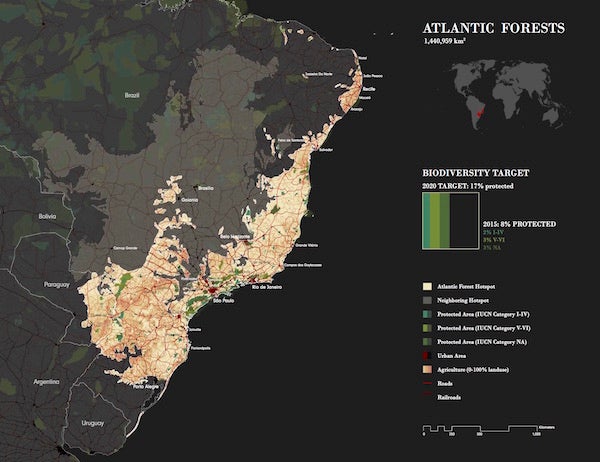

The Atlantic Forests hotspot serves as an example. Currently, it has only 8 percent of its territory under protection. Furthermore, when we break the hotspot down into its 15 constituent eco-regions, we find that nine fall short of reaching 17 percent representation.

An example of one of 35 of the world’s hotspots: The Atlantic Forests. Credit: Richard Weller

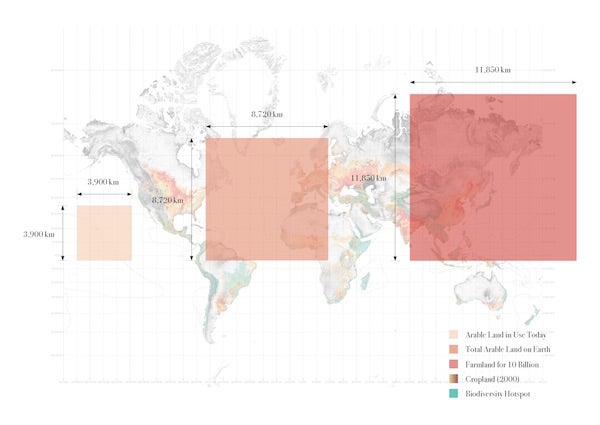

In total 21 of 35 hotspots currently fall short of reaching the 17 percent protected area target. More specifically, 201 of their 391 eco-regions fall short. With the new Atlas, any nation can know how much land needs to be protected and where if it wants to meet its obligations under the CBD. This is not to say that blanket targets are always appropriate on the ground, but it’s a start. In addition to identifying these protected area shortfalls, the critical nexus this research addresses is the global tension between food production, urbanization and biodiversity. On the world map (below) are three squares.

The first and smallest is the world’s current cropland. The second, in the middle, is current cropland plus current grazing land, plus what is thought to be the world’s further potential supply of arable land—a total of 50 percent of Earth’s ice-free surface area. These leave 50 percent of the planet’s land for other uses, exactly what E. O. Wilson has called for in his book Half-Earth: Our Planet’s Fight for Life. Fifty percent seems like a lot, but remember that 33 percent of this land is desert, which, by definition, is not suited to either biodiversity or agriculture. Subtracting the world’s deserts leaves 17 percent for biodiversity, precisely the amount demanded by the CBD.

The world existing and possible future foodbowl for 10 billion people. Credit: Richard Weller

The bigger cause for concern, however, is the large square on the right: the land area necessary to feed 10 billion people. The U.N. is now forecasting a global population of anywhere between 9.5 billion and 13.3 billion by 2100, so 10 billion is a conservative estimate. But these projected consumers are not “average” global citizens; let us suppose they are people like us; who shop in supermarkets and eat more or less whatever they want, whenever they want. They are average Americans; people with a food footprint of 1.4 hectares each.

Ten billion people consuming at this level would require a whopping 93 percent of Earth’s ice-free terrestrial surface. In this scenario, not only would all the world’s arable land be used for agriculture but so too would the world’s deserts, plus some. After we’ve finished our burgers, a mere 7 percent of Earth’s terrestrial surface would be left for biodiversity—for all practical purposes, a mountainous zoo in the midst of a global monoculture of corn and cattle, hooked up to desalination plants.

These proportions of land use will likely change when global population drops, as it probably will in the 22nd century due to socioeconomic influences associated with urbanization. The other mitigating factor would be if the bulk of food production shifted to the oceans and/or if meat could be produced independently of ruminants entirely. Then, ecological restoration could take place on a scale commensurate with that which is needed to partially correct the Earth system’s current imbalances. The challenge will be to get through this century’s incredibly tight ecological bottlenecks and come out the other end with some ecosystems, preferably the hotspots, partially intact.

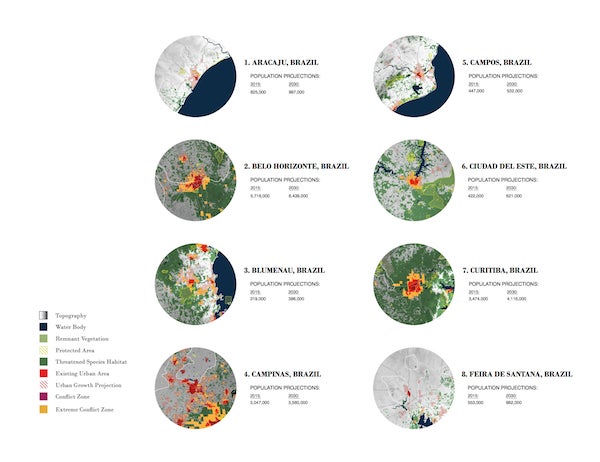

The second major area of this research concerns 422 cities in the world’s hotspots. We zoomed into each city of 300,000 people or more and superimposed their 2030 growth trajectory (as per Karen Seto’s work at Yale University). We then plotted remnant habitat and threatened (mammal) species from the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species. What emerge are the flash points between future urban growth and biodiversity.

Examples of some cities of more than 300,000 in the Atlantic Forest Hotspot (bright yellow and purple indicates imminent conflict with biodiversity). Credit: Richard Weller

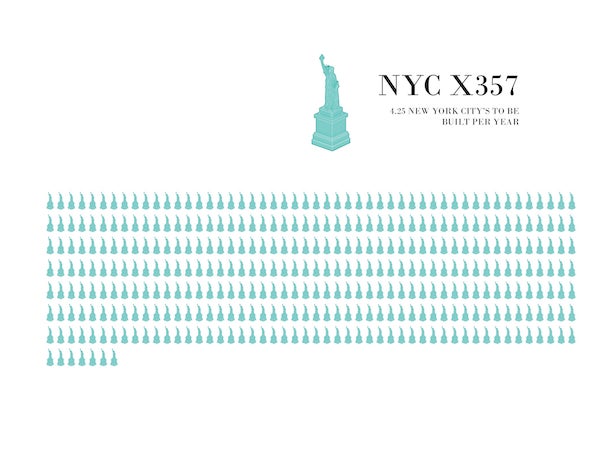

In the circular images of the cities in the Atlantic Forests hotspot, orange indicates zones of imminent conflict between urban growth and biodiversity. Alarmingly, 383 of the 422 cities in the world’s hotspots are on a collision course with unique and irreplaceable biodiversity. And we are not just talking about a little bit of sprawl. If an extra three billion people move into cities by 2100, as is entirely likely, it means we need to build 357 New York Cities in the next 84 years—that is, 4.25 New Yorks per year. Much of that growth will occur as both formal and informal sprawl in Africa, India and South and Central America, much of it up against biodiversity and much of it unregulated.

An extra 3 billion people moving into cities this century means we need to build 357 New York Cities.

As documented in the Atlas, our analysis suggests that most of these 383 cities that are encroaching on valuable habitat don’t have any semblance of as whole-of-city urban planning. This lack of planning at the city scale is also evident at the national scale: almost all the nations in whose jurisdiction the world’s hotspots lie don’t, insofar as we can tell, have national land-use plans incorporating biodiversity.

Under the CBD each nation must develop a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan. In practice, these tend to be platitudinous reports and most don’t take into account the 17 percent target for protected area. Most of the nations who are signatories to the CBD are also signatories to the Paris agreement on climate change, which demands that they prepare national climate change plans.

The Atlas for the End of the World lays the groundwork for the 142 nations who preside over the world’s biodiversity hotspots to now view climate change, biodiversity and urbanization as interrelated phenomena and plan for the future. To do so would be a new beginning.

REFERENCES

Paul Binding, Imagined Corners: Exploring the World’s First Atlas (London: Headline Book Publishing, 2003).

Pope Francis, Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home (Vatican Press, 2015), 33.

Convention on Biological Diversity, “List of Parties,”

D. Juffe-Bignoli, et al., “Protected Planet Report 2014,” International Union for Conservation of Nature (June 1, 2016).

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision, Key Findings and Advance Tables (2015).

An Ecomodernist Manifesto, “Manifesto.”

Karen C. Seto, Burak Güneralp, & Lucy R. Hutyra, “Global Forecasts of Urban Expansion to 2030 and Direct Impacts on Biodiversity and Carbon Pools,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States 109, no. 40 (2012): 16083-16088.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.