This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Part science documentary, part meditation on the meaning of life, director Terrence Malik’s (“The Tree of Life,” “The Thin Red Line”) new IMAX movie “Voyage of Time” is hard to categorize. Scientific American editors Clara Moskowitz and Seth Fletcher caught an early screening in New York last week. A few days later, they G-chatted their impressions of the film. A lightly edited transcript of that conversation follows.

Clara Moskowitz

What did you make of this movie?

Seth Fletcher

It's the first art-house planetarium movie I've seen, so I'm not sure what to compare it to. In some ways, I loved it. Visually, it was astonishing. I liked the huge sweep of it. The history of the universe from the beginning of time to the death of the sun, covered in 45 minutes. And yet, weirdly, it dragged a bit in the middle. There's a line in a Saul Bellow novel, I think Herzog, to the effect that the history of our planet and the evolution of life—all those billions of years of nothing happening—must have been, in the moment, so boring. After watching life crawl out of the oceans I was ready to move on.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

I know you had strong opinions about the voice-over narration.

Clara Moskowitz

To me the narration was so silly as to be distracting. Hearing Brad Pitt solemnly wonder, "Death, when did it first appear? Did it lead life forward?" or declare, "What binds us together makes us one. Love," made me laugh. If you didn't already know the basics about how stars and planets form and how scientists think life evolved, I don't think the narration would help you out much.

Seth Fletcher

They were obviously going for poetry over narration. But the poetry was pretty mediocre.

Clara Moskowitz

The clichés and "profundities" were coming on thick. But I do agree wholeheartedly on the gorgeous visuals. They were mesmerizing, and it's hard to complain about sitting and watching pure beauty for 45 minutes. I often found it hard to tell where the real footage ended and the special effects began. How much of a challenge do you think it was to achieve those effects?

Seth Fletcher

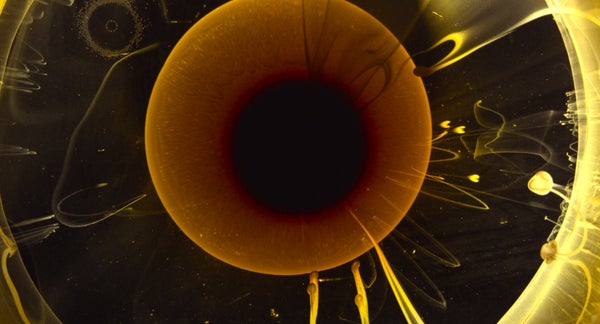

I have done zero research on the special effects, so I can't say, but they struck me as fresh and artful. Some of the cosmic stuff could have been footage of ink floating around in oil, for all I know, but it worked. Have you read the production notes they gave us, which probably explain how they did all this, but which I have been too lazy to read?

Clara Moskowitz

Yeah, I did take a peek, and you're not far off! They used things like "marmalade suspended in glycerin" and flow tables with poured milk and dyes and paints. They even shot "lit road flares dropping into boiling water."

Seth Fletcher

NAILED IT. Those scenes were my favorite part of the film.

Clara Moskowitz

You make a good point about the abstract imagery working better than attempts at realism. Which makes me wonder, do you think of this as a science film? Is the audience likely to learn anything about the origins and evolution of the cosmos, or was that not even the goal?

Seth Fletcher

That's a really interesting question. On one hand, audiences are going to see a compelling rendering of the history of the world according to our best scientific understanding. That is a pretty ambitious story to try to tell in a 45-minute IMAX movie! It starts with the big bang, and as far as I can tell, unfolds according to the standard model of cosmology. The solar system forms. Life emerges and evolves. Even if you only absorb the general arc of that story, you're learning a lot. But you're not going to learn many specifics. Neil DeGrasse Tyson isn't there dropping wondrous facts every 30 seconds. That might bother some people. What did you think?

Clara Moskowitz

At first I was expecting more explanation and elucidation. But there is also an argument to be made for letting the imagery wash over you and absorbing some of these ideas through osmosis, I suppose.

In the production notes there's an interesting quote from Harvard professor Andrew Knoll, the film's chief scientific advisor, saying basically that if he was in charge of making the film, it would have explained "what we know, how we know it and when it happened—but that's not Terry's mission," he says, referring to Malick. “His film asks something else entirely: how do we, as the products of this long evolutionary process, think about that process?"

Seth Fletcher

That's a pretty good explanation of what makes this an art-house planetarium film. And it makes me even more curious what's in the other version of this film—the one that is twice as long, narrated by Cate Blanchett, and that neither of us has seen. What do you know about that version?

Clara Moskowitz

I hear that the longer version is more overtly religious, where I think you could say the cut we saw was going for "meditative." Cate Blanchett apparently directly spoke to a god figure, wondering about how god made the universe. It also sounds like there were much heavier moral undertones—the nature and cosmic footage was interspersed with shots of present-day people around the world, including homeless people in the U.S. and Israeli-Palestinian conflicts, meant to make you think about how we're treating this world we've inherited and these other people that evolution has produced.

Seth Fletcher

Hmm. That doesn't sound promising. But I'll withhold judgment. When do the two versions come out?

Clara Moskowitz

The IMAX version that we saw comes out today in theaters around the country. The longer cut was apparently shown at the Venice Film Festival and the Toronto International Film Festival, but I haven’t heard about it getting a wide release. I’ll be curious to see what our readers think of the movie, because it’s definitely one where the viewer’s perspective, mood and expectations will play a big role in whether they come out satisfied or not.