This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

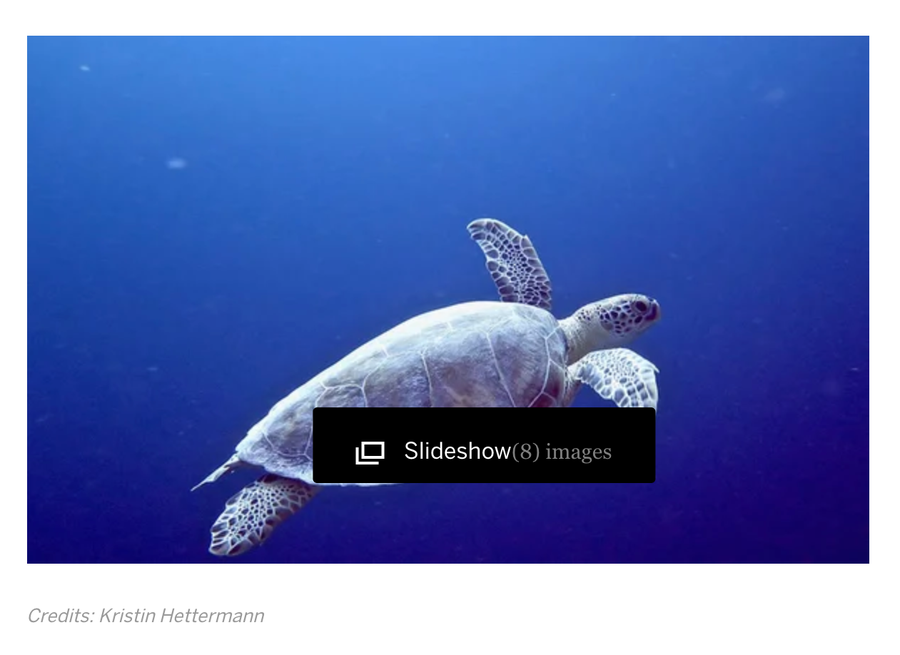

Fifty miles due north of Venezuela and 30 miles east of Curaçao is the uplifted coral reef island of Bonaire. Locals rightfully boast, of their natural treasures, including pink flamingos, iguanas on desert flatlands, a sea turtle nursery, large schools of many different types of reef and pelagic fish, rays, sharks, lagoons, wetlands, mangroves, yellow-shouldered amazon parrots, a jewelry box of hard and soft corals and sponges and so much more. For many reasons, this island now stands as a prime example of a protected environmental asset.

In 1963, an American sailor named Don Stewart was sailing the Valerie Queen, a 1912 70-foot wooden topsail schooner, around the Leeward Antilles in the Caribbean Sea. He shipwrecked on the fringing reef around Bonaire, on the continental shelf of South America— and the rest is ocean conservation history. “Hurricane-whipped with only 63 cents and my ship’s papers in my pocket,” he wrote, “I sought refuge on the small island of Bonaire, an old Dutch Colony rooted deep in the southern Caribbean. The Governor said, ‘A bum you become, you’re out. However, if my island is better off because of you....’ A challenge made.”

Captain Don started his life on Bonaire spearfishing for sustenance and income. But while hosting one the island’s first spearfishing competitions, he realized the devastation such events could cause through the overextraction of resources, and decided fishing was no longer for him. He had a premonition about what the human species would do to our ocean in the future.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Recognizing the pristine and abundant lushness of Bonaire’s marine environment, he thus began a life devoted to ensuring responsible and sustainable tourism. His intuition and dedication resulted in one of the planet’s most diverse, entertaining and easily accessible marine environments.

As ocean explorers around the world know, all of Bonaire’s coastline and the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that surrounds it have been legally protected since 1979. The Bonaire National Marine Park, a global leader in ecological responsibility and conservation, includes 2,700 hectares (6,700 acres) of fringing reefs, seagrasses and mangroves. The protected area goes from the high-water mark down to a depth of 60 meters.

Stewardship is a key mantra, given that more than 470 species of fish and 57 species of hard and soft coral live on Bonaire's reef. In 1992, the park became one of the first diving destinations to introduce admission fees, doing so for its 86 named dive sites.

After seeing the waters around Bonaire for myself I wondered … what happens to reefs like these as the climate changes? With sea temperatures and sea levels rising, escalating threats from storms and an ocean growing constantly more acidic, the future doesn’t look like a pretty picture.

Hurricanes might be the most immediate threat. Despite the fact that these islands are officially located outside of the hurricane belt, the past 30 years have brought more unpredictable weather to the entire region, including, Hurricane Lenny in 1999, Hurricane Omar in 2008 and Hurricane Maria in 2016.

“We did see that the healthiest reefs weathered the storms the best,” Kristen Marhaver wrote to me from Curaçao, where she is a senior scientist at CARMABI (Caribbean Research and Management of Biodiversity) Marine Research Station. But, she added, “on degraded reefs near heavily-developed and polluted areas, the dead corals turned into bludgeons that the surge used to hit the other corals.”

But Curaçao's remote reefs in East Point, which are still thriving due to a lack of coastal development, stayed strong. “Healthy coral reefs slow down wave energy and buffer coasts from the surge.” Marhaver wrote. “They also create habitat for the fish we eat, clean the seawater through the ecological collaborations of thousands of species, and provide playgrounds for snorkelers and divers and scientists to learn from and explore. It's a win-win-win-win.”

Studies have shown that in the past 100 years the sea has risen 5–8 inches on average (although in some parts of the world the figure is 10–15 inches). Since the beginning of the industrial revolution and the introduction of large-scale coal burning, the atmosphere has been trapping more and more heat, and the ocean has stored 93 percent of it. According to an ongoing temperature analysis conducted by scientists at NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, the average global temperature on Earth has increased by about 0.8 degrees Celsius (1.4 degrees Fahrenheit) since 1880. Two thirds of the warming has occurred since 1975, at a rate of roughly 0.15–0.20 degree C per decade.

The resulting increase in sea level and warmer ocean temperatures have led to stronger tropical storms, with an increase in category 3, 4 and 5 hurricanes and a decrease category 1s and 2s. Robert Corell of the University of Miami and Principal of the Global Environment and Technology Foundation, explained this phenomenon to me in simple terms. “The energy of a storm is increased by increased surface temperature. Hurricanes get energy by the increased warm spots in the water,” he said, also referencing the unprecedented 90-degree water off of Cuba and Puerto Rico during the time of Hurricane Maria. “Every foot of sea level rise on average will increase the storm-system reach 300 feet.”

A hurricane that hits a stressed reef causes long-term damage. “The reefs do tend to recover, but it can take decades, especially on sandy areas and algae-covered shallow reefs, where there's less live coral to cement the whole structure together,“ writes Marhaver, who is well known in the Caribbean coral biology world and as an expert on coral spawning. “After a big storm, already-stressed reefs will slide further down and become less healthy. It certainly shows that 'normal' hurricanes are something a coral reef has evolved to deal with on occasion … but a climate change-fueled hurricane on a stressed reef causes far greater long-term damage. Recovery can take decades or centuries instead of just a few years.”

For that reason, reef conservation and protection are vital to survival in a world experiencing climate change. If a place like Bonaire—with its thriving marine landscapes and visionaries willing to take action moves to protect the local marine environment—can stay healthy, it is best poised to weather the coming storms.