This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

WASHINGTON, D.C.—Amidst a tempest of election season political turbulence, a wave of bipartisan unity appears to be rising in support of research targeting Alzheimer’s disease. “Every one of us knows how vulnerable we are,” says Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill), speaking at a forum in Washington D.C., organized by AtlanticLIVE. The Democratic senator shared the stage with his Republican colleague Susan Collins of Maine, who warned that the nation is facing a “tsunami of cases.”

In fact, as baby boomers enter old age and people are living longer, the number of cases will triple from 5.3 million today to 16 million in 2050, according to the Alzheimer’s Association, which is holding its annual international conference here this week. Nearly half of the people who reach the age of 85 will succumb to this most common cause of dementia. “Alzheimer’s disease is going to bankrupt Medicare and Medicaid,” Collins says. “We cannot afford not to make this investment [in research].”

The Atlantic's Steve Clemons with Senator Dick Durbin and U.S. Senator Susan Collins at #AtlanticAlz | Photos by Kristoffer Tripplaar

Posted by AtlanticLIVE on Tuesday, July 21, 2015

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Funding for Alzheimer’s research seems to be emerging as a possible exception to the long string of miserly cuts in federal spending. “This is special,” Durbin says. “I believe this issue covers the spectrum [of political opinion].”

“Constituents resonate to Alzheimer’s disease,” says Collins, who sees widespread support for research across her party. Even ardent critics of the contentious Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”), including Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) and former Florida Governor Jeb Bush, are united with liberal Democrats on this issue. Collins cites a concrete example: “Republicans are in control of the Senate and they just authorized a 60 percent increase in Alzheimer’s disease funding.”

Members of Congress on both sides of the aisle are calling for a national strategy to defeat Alzheimer’s disease, modeled on the rapid response to the AIDS epidemic or the war on cancer started 40 years ago. Last week Collins proposed new legislation to address the lack of Medicare coverage for long-term care, for example to provide the custodial in-home care that an Alzheimer’s patient must have. Senator Durbin has proposed a 5 percent annual increase in budget to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) over the next 10 years to make the necessary investment for breakthroughs in Alzheimer’s disease and other biomedical research.

From Durbin’s perspective this issue goes beyond improving health and relieving human suffering; he sees biomedical research as a matter of national security and economic competitiveness. The number of research grants funded by the NIH has declined every year for the past 10 years. Between 1999 and 2009, Asia’s share of worldwide research and development expenditures grew from 24 percent to 32 percent. Meanwhile, American expenditures fell from 38 percent to 31 percent.

Biomedical research, Durbin notes, is a powerful force for economic growth. He cites the Human Genome project as an example where the federal investment has been paid back many times over in technological development and economic gain. “America’s place as the world’s innovation leader is at risk as we are falling behind in our investment in biomedical research,” he says.

There’s little question that more funding for Alzheimer’s research makes sense. Despite the demographic tsunami, investment in Alzheimer’s is currently dwarfed by spending on heart disease and cancer. But Congressional enthusiasts of all stripes should be prepared for the fact that much like the “war on cancer”, an all-out assault on Alzheimer’s is unlikely to yield a cure. Progress will likely take a different, more piecemeal shape.

This is because Alzheimer’s disease and dementia are a multifactorial problem, says Richard Mohs, Vice President for Neuroscience Clinical Development at Eli Lilly and Company, who also spoke at the forum. Looking to the future from his perspective in the pharmaceutical industry he predicts, “I don’t think we’ll see the disease disappear, at least not in my lifetime. But the risk will go down, just as it has with heart disease.”

This is far more than a glass-half-full view of the problem, because slowing the progress of the disease may be enough to make a sizeable dent in both suffering and economic cost. “Slowing the disease is essentially a cure for many,” Mohs says, “because of their advanced age.”

“If we can delay onset even five years, it pays for the cost of research,” Collins adds, because the cost of caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease is so enormous. Mohs predicts that the solution to Alzheimer’s disease will involve a combination of life-style changes (including diet and exercise) and drug treatments, much the way diabetes and cardiovascular disease are managed successfully today.

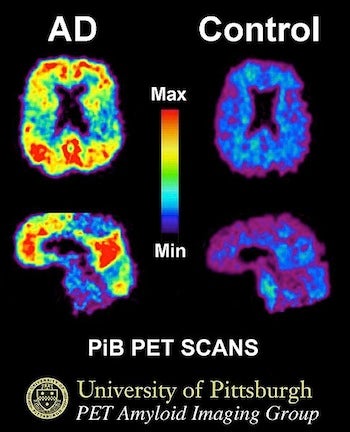

This image shows a PiB-PET scan of a patient with Alzheimer's disease on the left and an elderly person with normal memory on the right. Areas of red and yellow show high concentrations of PiB in the brain and suggest high amounts of amyloid deposits in these areas. (Source: University of Pittsburgh/Wikimedia Commons)

The key will be early diagnosis. PET (positron emission tomography) scanning is a brain imaging technique that can detect amyloid deposits in the brain 10 to 15 years ahead of the memory loss. These deposits eventually damage brain cells and cause dementia. Drugs that have been developed to attack these deposits of amyloid protein show some promise, but they don’t cure the disease. (In fact, in some cases these drugs have worsened the disease.) The consensus of experts is that drug treatment must be started early, before years of slowly advancing pathology reach a point of no return.

This is why identifying risk factors and early signs of Alzheimer’s disease at the pre-symptomatic stage is so important. PET scanning can do this a decade before symptoms begin to appear, but the technique is specialized, expensive and invasive. Unlike MRI brain imaging, PET requires the injection of radioactive substances into patients in order to reveal amyloid deposits in the brain. Faster, cheaper, safer methods are badly needed, which is why there was much excitement at this week’s conference about preliminary successes with new tests that detect Alzheimer’s related proteins in cerebral spinal fluid and even saliva. If simple, low-cost tests become available to detect pre-symptomatic changes in the brain, then treatments could be started early enough to knock out amyloid deposits before the brain becomes severely damaged.

Alzheimer’s disease affects not only the person afflicted, erasing their memories and leaving them isolated and confused, it affects everyone in the family. Collins, who recently introduced bipartisan legislation to support family caregivers, says she knows this from first-hand family experience: “Alzheimer’s disease affects even a grandchild whose name is no longer remembered.”

An estimated 43 million family caregivers are currently dealing with the chronic debilitation and onerous needs of loved ones with Alzheimer’s. That’s an estimated $450 billion in uncompensated long-term care. Americans aged 85 and older are the fastest growing segment of the population. What we are seeing is only the start of what is certainly a health care tsunami about to roll over America. The new federal funding proposals can help us prepare.

Editor's Note: Douglas Fields is an employee of the National Institutes of Health, but is writing here in a personal capacity; the views expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of the federal government.