This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

When NASA's New Horizons mission launched in January 2006 the known moons of Pluto consisted of Charon (arguably more of a binary companion than a moon), and Nix and Hydra - spanning some 42 and 55 kilometers across respectively.

Remarkably, during the spacecraft's ten year, 5 billion kilometer cruise to Pluto, astronomers were able to use the Hubble Space Telescope to spot two more natural satellites - Kerberos (announced in 2011) and Styx (announced in 2012) as tiny points of reflected light.

Hubble discovery image of the smallest moons of Pluto (Credit: NASA, ESA, L. Frattare STScI)

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now the data returning from the spacecraft, carefully processed and analyzed, has provided our first ever - and possibly our last ever - family portrait of all of these diminutive bodies.

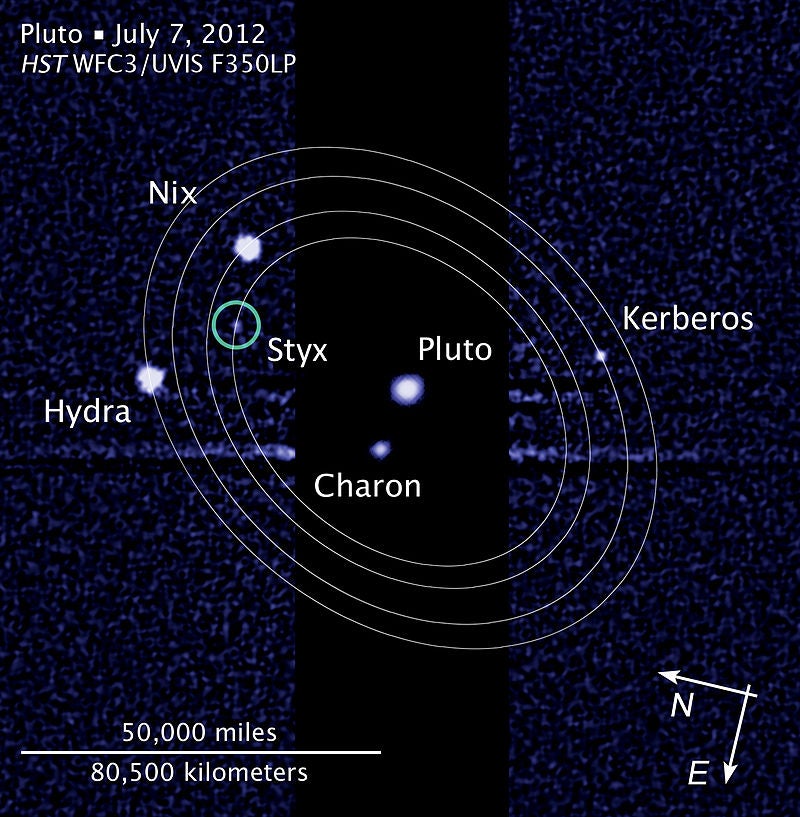

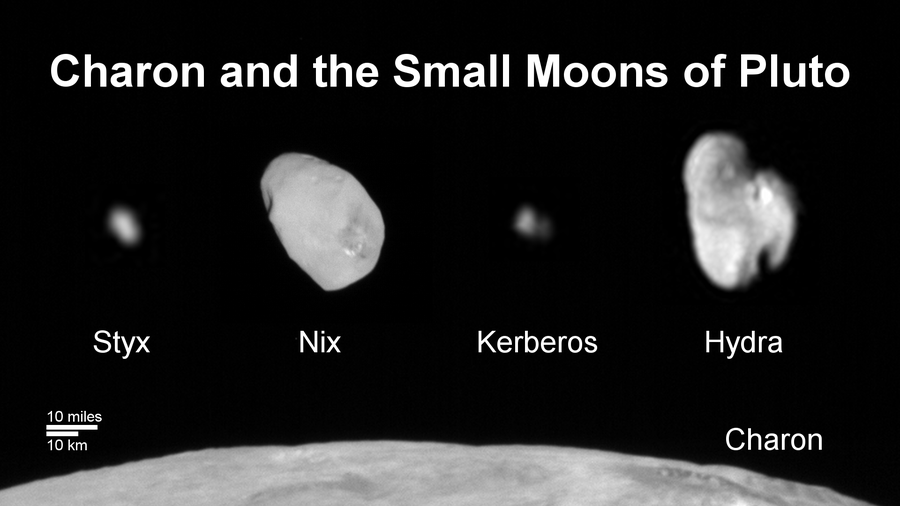

A portrait of moons (Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)

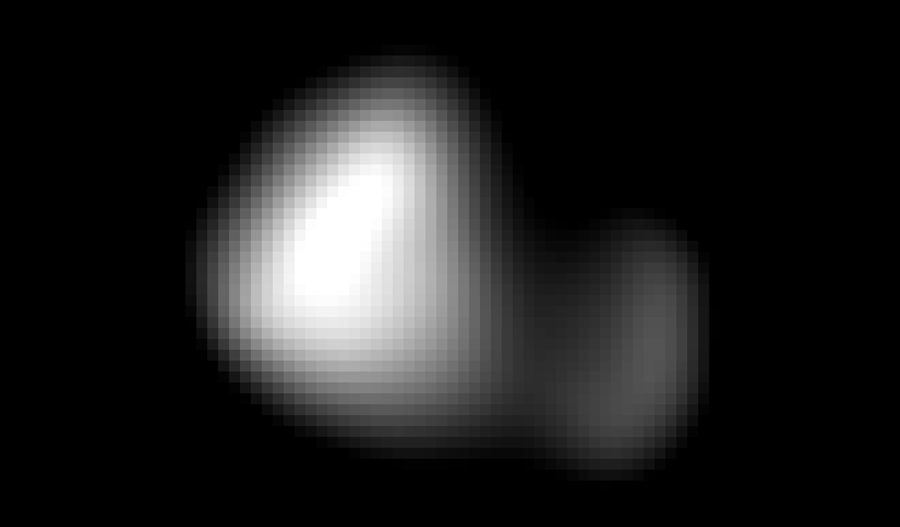

Little Kerberos turns out to be smaller than expected, and seems to consist of two 'lobes', one about 8 kilometers across, the other about 5 kilometers. Its reflectivity suggests a water ice surface. This shape also suggests that it formed by the merger of two bodies, slapping together non-destructively.

Intriguingly, a smaller Kerberos contradicts predictions from measurements of its gravitational influence on the other satellites - which indicated a more massive body. What's up with Kerberos? We don't yet know.

The best image of Kerberos we may ever get - made by combining images and software deconvolution and smoothing (Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI)