This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The universe is full of objects that conspire to get in each others way. It's positively perverse, the vast bulk of the cosmos is emptier than a politician's moral bank account, yet where there are tiny condensations of matter they seem unable to leave each other alone.

Of course there are reasons for this. The way in which stars and planetary systems form has certain symmetries and processes that tend to bunch matter together into orbital configurations and rhythms where, over time, geometric alignments and patterns can occur. Place yourself in the right viewing spot and all manner of wonderful coincidences take place.

Our own Earth-Moon-Sun system is a good example. The mutual orbital planes of these three objects sets us up for shows of eclipsed light and shadow, again and again, and again over time. But there are other variants on the theme of eclipses all across the solar system and beyond.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

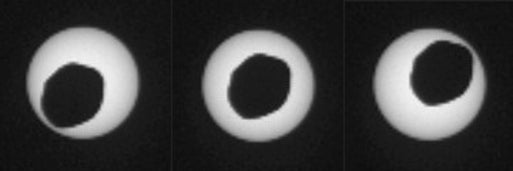

Phobos eclipse. Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, Malin Space Science Systems, Texas A&M

Mars is a nice example, especially because we (or rather our robotic avatars) have seen solar eclipses there first hand. The two martian moons, Phobos and Deimos, are relatively diminutive things. Phobos is a lumpy 23 kilometers across, and Deimos is about 12 km across. They seem hardly capable of blotting out much of anything on the sky.

But both orbit very close to Mars. Phobos whizzes around every 7 hours and 40 minutes at an altitude of only 9,300 km (rising and setting twice during one full day on Mars), while Deimos takes a leisurely 30 hours at a much greater distance of some 23,000 km. Because Phobos orbits so closely, and because the Sun seen at Mars spans an angle on the sky of only about 0.32 degrees (when Mars is furthest from the Sun) Deimos can actually produce a decent, albeit incomplete, eclipse.

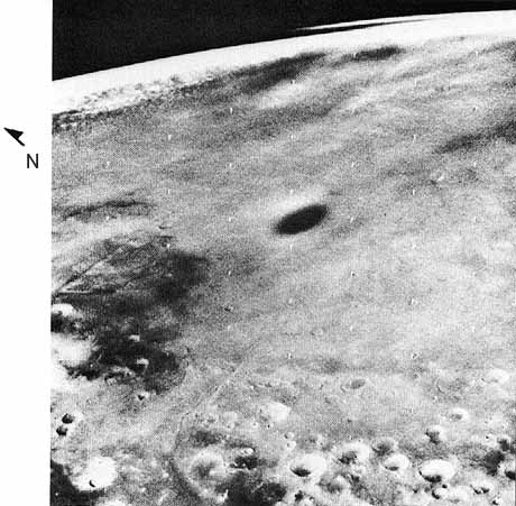

Phobos Shadow Transit over the Viking Lander 1 Site. Credit: NASA, JPL

Here's a beautiful time-sequence of Phobos eclipse shots taken by the Curiosity rover in 2013 at close to midday (when Phobos actually appears larger on the sky because it's closer to the rover). With an angular diameter of about 0.14 degrees Phobos doesn't blot the whole Sun out - but it definitely makes a fair stab at it.

Phobos shadow on Mars. Credit: NASA, JPL, Malin Space Science Systems

The real kicker though is that this happens almost every day somewhere on Mars between the latitudes of 70 degrees north and 70 degrees south, since Phobos orbits almost directly above the martian equator.

That also means that we've spotted the Phobos eclipse shadow from orbit. Even the Viking 1 orbiter saw the shadow (helping pin down the location of the lander, which sensed the eclipse simultaneously with the orbiter).

And more recently, here's a glimpse of the shadow from Mars Global Surveyor in 1999.

These partial eclipses are fleeting affairs, taking barely 30 seconds to sweep across any location. But they're a great reminder that while Earth may be treated to near-perfect solar eclipses (at this point in the Earth-Moon orbital history), we're also not so very special.