This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The very last days of the Cretaceous might seem to be the apex of dinosaurian tyranny. After all, the last two million years of the Mesozoic hosted our favorite bone-shattering carnivore of most any era – Tyrannosaurus rex. But the biggest or most widespread member of a ravenous family doesn’t necessarily indicate peak evolutionary performance. Ten million years before T. rex, up and down the ancient North American subcontinent of Laramidia, there stalked a variety of different tyrannosaur species. And paleontologists are finding more all the time. The question is how to identify which tyrannosaur we’re looking at.

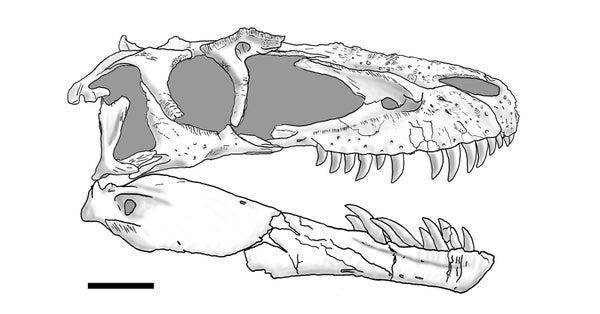

Consider the case of a fossil called TMP 1994.143.1. This lovely little skull, just redescribed by paleontologist Jared Voris and colleagues, was initially identified as a young Daspletosaurus. Along with Gorgosaurus, this was one of two tyrannosaurs that ran around Cretaceous Alberta around 76 million years ago. Even more importantly, TMP 1994.143.1 was the only juvenile Daspletosaurus known. All the other specimens – of any Daspletosaurus species – are subadults or older. But the discovery of a new tyrannosaur skull fossil led Voris and coauthors to have another look at TMP 1994.143.1. It’s not the dinosaur paleontologists first thought it was.

The key specimen is called TMP 2013.18.11. The fossil isn’t as pretty as the juvenile skull. In fact, it’s just a single bone – a postorbital, or a bone that makes up the rear border of the eye and has some of the bumpy ornamentation that made tyrannosaurs so striking. But when Voris and colleagues looked at this bone, it shared more in common with the equivalent bones in adult Daspletosaurus than with the famous juvenile skull. If the single bone belonged to a young Daspletosaurus, but didn’t match TMP 1994.143.1, then obviously the more complete juvenile skull represents a different dinosaur. Voris and colleagues propose that dinosaur is the slender tyrant Gorgosaurus libratus.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What does this mean for paleontology? For a while now, the researchers point out, some experts have thought that fossils of juvenile tyrannosaurs are relatively generalized, or they don’t offer many definitive clues to what species they belong to. But the reshuffling of these two Alberta fossils indicates that young tyrannosaurs really do have hard-to-spot traits that tie them to particular species. In other words, Voris and colleagues write, their results “demonstrate that juvenile albertosaurines and tyrannosaurines, and probably juvenile tyrannosaurids in general, can be more readily differentiated than previously thought.”

Given the fame of tyrannosaurs, and the last of their kind in particular, these new findings raise questions about the identity of other juvenile tyrannosaur skeletons. More than a little ink has been spilled over whether “Nanotyrannus” existed or if all the fossils assigned to that dinosaur are just young T. rex. (On that score, it’s worth pointing out that Voris and coauthors consider the famous “Cleveland skull” previously assigned to “Nanotyrannus” to be a young Tyrannosaurus.) Just because one fossil shifts identity doesn’t mean that the past decade of dedicated work on juvenile tyrannosaurs is overturned. Instead, the findings mean that – difficult as they can be to identify – young tyrannosaurs really do preserve useful characteristics that can help paleontologists sort out their families, and that the more we uncover the more we can test what we previously assumed. As the tyrannosaur rush of the early 21st century continues, it’s a point worth remembering.