This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Dinosaurs have lived on Earth for over 235 million years. That means they’ve also been dying for just as long. And when they die – whether we’re talking about a Parasaurolophus or a hummingbird – dinosaurs often take up a classic death pose. The head is thrown back over the body, sometimes almost touching the spine, and dinosaurs with long tails often have those balancing appendages curled upwards in an arc.

Paleontologists have been debating the cause of the dinosaur death pose for over a century now. There are two schools of thought on the subject. Some researchers have proposed that the contortion – technically called the opisthotonic posture – is caused at the time of death by poisoning, lack of oxygen to the brain, or similar circumstances that cause neck and tail to spasm into weird angles. Other paleontologists have suggested that the pose happens after death, with immersion in water or decay tensing muscles and ligaments that pull the head back and the tail up. It could be a perimortem or postmortem pose.

Both groups may be right. There seems to be a variety of ways for dinosaur skeletons to creak into the strangely-beautiful positions many of them are found in. But relatively little has been done to understand why dinosaurs and some of their prehistoric relatives, like pterosaurs, were even capable of such a pose. That’s what led biologists Anthony Russell and A.D. Bentley to X-ray a set of ten thawed, plucked chickens.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

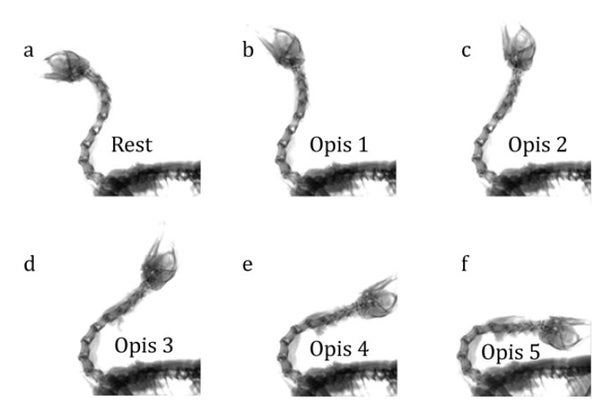

Chickens, like all birds, are dinosaurs, and they have the advantage of being readily available at the supermarket. So after thawing out their frozen birds, Russell and Bentley placed the birds in different opisthotonic positions starting at rest and moving the neck back until it mimicked what’s seen in fossil dinosaurs like the Struthiomimus on display at the American Museum of Natural History. They also checked to see if the birds’ heads could be flexed forward, beneath the body, and the researchers used the X-rays from both sets of trials to see how neck vertebrae angles changed with each position.

Chickens in varying degrees of opisthotonic posture. Credit: Russell and Bentley 2015

It actually didn’t take all that much for the birds to get to the dinosaur death pose. The posture, Russell and Bentley write, “can, in chickens at least, be facilitated simply through the limpness associated with death combined with the imposition of a relatively modest displacing force.” Getting the neck to arc downwards was something different altogether. The chickens’ necks locked when they were angled down and required significant force to keep them that way. The natural thing for a dinosaur neck to do is to arc backwards.

The greatest changes happened in the middle of the neck. While the base and the very front of the chicken necks didn’t move much, Russell and Bentley found that two neck joints in the middle changed their orientations significantly and contributed the most to the pose. The flexibility of the skull helped, too. The spot where skull meets the neck stayed flexible in every position, and this undoubtedly helped some dinosaur skeletons achieve the posture where snout touches hip. This might also explain why many fossil dinosaur skeletons are found decapitated. Perhaps the anatomy that gives the skull a wide range of motion also allows it to easily be lost as soft tissues decay, letting heads roll as the rest of the skeleton is pulled towards becoming an osteological circle.

So while there’s probably an array of immediate causes for the dinosaur death pose, the ability for the saurians to take up the posture at all is because of flexible necks that can more easily be retracted back than pressed downwards. That’s the past of least resistance, literally, at or after the time of death, and why today’s dead chickens and emus look like they’re doing impressions of their fossilized predecessors.

Reference:

Russell, A., Bently, A. 2015. Opisthotonic head displacement in the domestic chicken and its bearing on the ‘dead bird’ posture of non-avialan dinosaurs. Journal of Zoology. doi: 10.1111/jzo.12287