This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Out in Utah’s eastern desert, nestled among the purple- and red-banded hills of the Morrison Formation, there rests one of the richest dinosaur bonebeds ever found. It’s also the most mysterious. Since the site’s initial discovery over a century ago, the jumbled remains of over 46 Allosaurus – as well as the comparatively rare bones of other Jurassic dinosaurs – have been pulled from this one spot, and there’s every indication that there is more to be found than has yet been uncovered. But what brought all these dinosaurs here, and why do predators dominate this spot when almost every other bonebed of its kind has the expected array of abundant herbivores and rare carnivores?

There are almost as many takes on what created the bonebed at Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry as scientists who have studied it. The initial, and most obvious, idea was that this was a predator trap like the La Brea asphalt seeps. Some poor herbivore got stuck in mud, died, and its rotten stink drew scores of Allosaurus here, which became trapped in turn. But there’s no tar or other trapping mechanism to do the dirty work. This led to other suggestions – that the dinosaurs were killed by drought, that the site was a poison spring, that the dinosaurs died elsewhere and their carcasses were washed to the spot – but there was always some point that didn’t make sense or remained contentions. Where some experts saw a dry environment, others saw one that was frequently wet. Where some saw evidence of one catastrophic event, others saw multiple depositions that happened over time.

That’s what led geoscientists Joe Peterson, John Warnock, Steven Clawson, and their colleagues to move literal tons of rock and excavate Cleveland-Lloyd anew. Not for new bones, but for the geological clues that might let the researchers more accurately envision what happened there in the days of the Late Jurassic. What they’ve found doesn’t conclusively solve the Mesozoic murder mystery, but it refines the setting where the inscrutable events took place.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Peterson and coauthors looked at the fossil assemblage from two angles – a geological technique called x-ray florescence to determine the geochemistry of the Cleveland-Lloyd rocks and a detailed analysis of bone fragments found within the quarry. Together, these two lines of evidence help outline what must have been an incredibly smelly Jurassic scene.

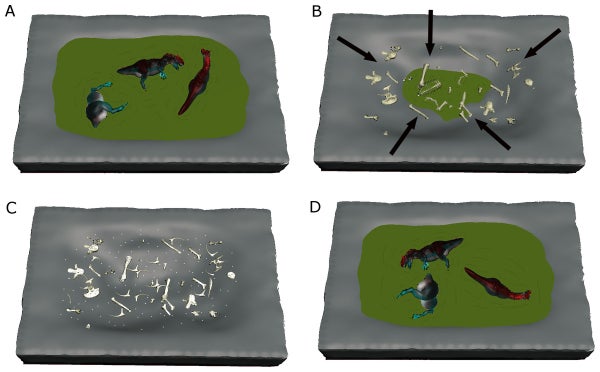

While it’s certainly dramatic to think of hundreds of dinosaurs accumulating in one spot all at once, the findings of Peterson and his colleagues suggest that Cleveland-Lloyd didn’t form in a single event. This spot in the Utah desert was once an ephemeral pond that came and went as the Jurassic seasons shifted from wet to dry. And during the wet times, local flooding transported dinosaur bodies and bones to this particular spot where they settled.

How the CLDQ bonebed was formed, starting with carcasses being washed in, bones being exposed, bones being weathered and broken into fragments, and the addition of more carcasses in the next flood stage. Credit: Peterson et al 2017

The bone fragments help tell the story. The patterns of abrasion and other details suggest that the fragments came from bones already within the pond deposit, getting jostled and reworked with the swings between the seasons. Likewise, the geochemical results supported that this was a wet spot for at least some times of the year. In fact, the analysis showed that the Cleveland-Lloyd sediments had unusually elevated levels of heavy metals compared to other bonebeds of similar age. This doesn’t mean that Cleveland-Lloyd was a poison spring – as has also been suggested to explain the carnage – but that the geochemical profile is instead a sign of rotting carcasses sitting in a standing body of water, turning the pond into an undrinkable, mineral-rich soup. And this could explain why fossils of fish, turtles, and crocodiles are rare in the quarry, as well as why bite marks and signs of scavenging are so rare. When full, this was a rank spot with foul water that was best avoided.

What the new study does is look at the environment of Cleveland-Lloyd over the span of Jurassic seasons. It sets new parameters for thinking about, and questioning, what happened there over 145 million years ago. The site was an ephemeral pond, and it didn’t come together all at once. That may sound simple, but it sets a new baseline for interpreting how such an unusual site came to be.

Plenty of questions remain. If the dinosaurs were washed in, then what killed them in the first place? And does this deposit represent especially harsh times – like intense, recurring droughts – or does it encapsulate the normal comings and goings of dinosaurs during the Late Jurassic? On top of that, we still don’t know why Allosaurus is overrepresented at this site compared to almost every other Morrison Formation bonebed of its kind.

Perhaps something unusual was happening in the vicinity that caused Allosaurus to congregate. Then again, the "different lizard" was by far the most common carnivore of the Late Jurassic west – if you find a theropod in the Morrison, nine times out of ten it’s going to be Allosaurus – and so exhuming an abundance of Allosaurus in a deposit that formed over years and years might not actually require a special explanation other than the predators were abundant at that time. In fact, a few hours away from Cleveland-Lloyd just over the Colorado border, there is another, smaller bonebed where Allosaurus dominates. Perhaps Cleveland-Lloyd represents just another slice of regular Jurassic life rather than something unusual that requires special explanation. Then again, as Peterson and colleagues write, it’s possible that the surfeit of Allosaurus at Cleveland-Lloyd is pointing towards previously-unknown aspects of their behavior – perhaps there was a breeding or nesting site nearby, or maybe these dinosaurs were brought into closer numbers in times of drought and then die as is seen with modern animals in sharply seasonal habitats.

The story of Cleveland-Lloyd is far from told. The conditions that created the bonebed, and what led to Allosaurus being buried in unprecedented numbers, are still unknown, not to mention all the other paleobiological and ecological details still embedded in bone and rock. But the new study is a significant step in reconstructing what happened during the days when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. And by starting with how they died, maybe we can learn something new about how these amazing animals lived.

Note: Although I had no role in the present study, I’ve joined Peterson’s field crew at Cleveland-Lloyd during the past three summers and assisted in the exploration and excavation of sites in the vicinity of the main quarry.

Reference:

Peterson, J., Warnock, J., Eberhart, S., Clawson, S., Noto, C. 2017. New data towards the development of a comprehensive taphonomic framework for the Late Jurassic Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, Central Utah. PeerJ. doi: 10.7717/peerj.3368