This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

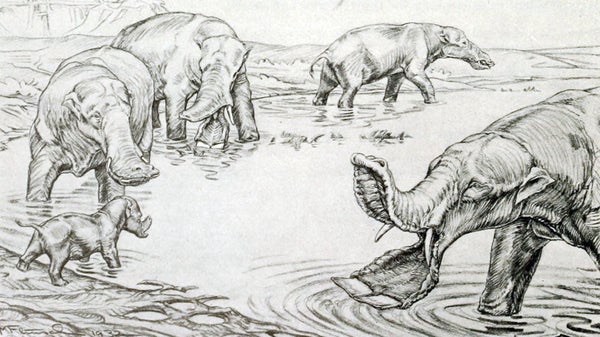

One look at Platybelodon and you know why the beast has been called a shovel-tusker. The publication describing one of the most abundant species, Platybelodon grangeri, even went so far as to illustrate the lower jaw of one of these fossil elephants next to a shovel in case the resemblance wasn't immediately clear. But appearances can deceive. As it turns out, Platybelodon wasn't a shovel-tusker. It may have been more of a saw-tusker.

You can hardly fault 20th century paleontologists for plunking Platybelodon in swamps where the behemoth could scoop up great mouthfuls of soft plants and algae. That's simply what it looked like it should be doing. But in 1992 paleontologist David Lambert suggesting something that went against the grain. After studying the teeth of scoop-mouthed elephants such as Platybelodon and Amebelodon, Lambert concluded that the microscopic damage on their teeth indicated that these beasts were scraping bark or even rubbing plants against their flattened incisors to cut them.

Now paleontologist Gina Semprebon and colleagues have confirmed what Lambert suggested over two decades ago. Drawing from an entire growth series of Platybelodon grangeri from the 15-11 million year old deposits of Linxia Basin, China, the researchers looked for scratches, pits, scars, and other damage that are associated with different diets. An animal that grazes on tough grasses, for example, will show a different pattern of damage than one that eats soft leaves. In the case of this extinct elephant, what the paleontologists found was at odds with the classic image of Platybelodon plowing its squared-off tusks through the muck.

The constellation of scratches and pits on Platybelodon molars, Semprebon and coauthors found, resembled the pattern seen on today's African forest elephant. Platybelodon likely browsed on leaves, although differences between the youngsters and adults hints that the older elephants ate coarser vegetation and twigs more often.

As for those peculiar lower tusks, there were no gaping gouges or scars as would be expected if the mammal used its mouth as a shovel. Instead it seems that the wear on Platybelodon tusks fits Lambert's idea that these elephants were stripping bark from trees or even using their trunks to rub vegetation against their lower tusks, shredding it into smaller morsels.

Just imagine it - a massive elephant scraping its shovel-shaped mouth against a fallen tree trunk, taking in a mouthful of twigs and leaves. And if Platybelodon was stranger than we ever expected, the same might be true of the other elephants previously considered "shovel-tuskers." Amebelodon from North America, for example, had longer, narrower lower tusks, and just this year Lambert named a new and little-known species from Oregon that's "unusual" compared to all the others. What were these elephants doing? How did they live? To find out, paleontologists will have to look them in the mouth.

Reference:

Semprebon, G., Tao, D., Hasjanova, J., Solounias, N. 2016. An examination of the dietary habits of Platybelodon grangeri from the Linxia Basin of China: Evidence from dental microwear of molar teeth and tusks. Palaeogreography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. doi: 10.1016.j.palaeo.2016.06.012