This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Stroll through any museum hall well-stocked with fossil mammals and it’s tempting to look at the extinct beasts as variations on recognizable themes. There’s a sloth, but bigger. There’s a camel, but smaller. I guess that weirdo in the corner looks something like a pig. We shove the remains of the extinct into expectations of the familiar even if the fit isn’t particularly good. And that’s a shame. Fossil mammals were stranger than we often give them credit for, and they often behaved in ways that no modern animal does. Just look at Kolponomos.

In the wide spread of the mammal family tree, Kolponomos was a carnivoran. That’s the group that includes cats, seals, bears, civets, and the dog snoring on the couch next to me as I write this. From there the phylogenetic haze sets in, however, with the 20 million-year-old Kolponomos fitting in somewhere around bears and their extinct relatives the bear-dogs, but not really belonging to either line. Regardless of which group can claim Kolponomos, however, what makes this beast so strange was the way it fed. This almost-bear bit like a sabertoothed cat, crunching mollusks in grizzly-like jaws studded with otterish teeth.

The idea that Kolponomos fed on shellfish has been around for a while. The mammal has been found in marine rocks from Oregon, Washington, and possibly Alaska, and the cheek teeth of these fossils show extreme wear from a diet of hard foods. In fact, Kolponomos so regularly dined on clams and mussels that the blocky crushing teeth are often “lakes” of softer dentine with the harder enamel fencing them in. Yet no one had tested this idea, nor how Kolponomos went about prying its food up from rocky shores. Now paleontologist Jack Tseng and colleagues have finally looked Kolponomos in the mouth.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

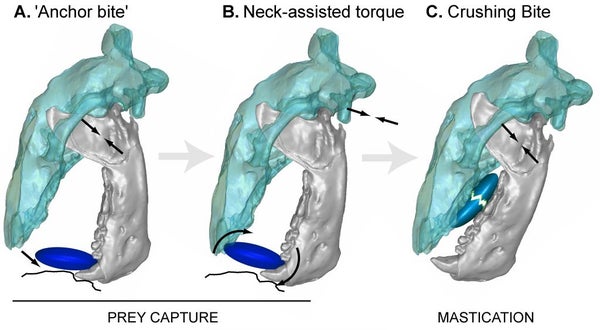

From the anatomy of the shoreline mammal’s jaws, Tseng and coauthors expected that it shared a habit in common with saber-toothed cats. The front of the jaw in Kolponomos is deep and buttressed, giving it a prominent chin just like the famous sabercat Smilodon. In the cats this condition is thought to reflect an attack strategy of anchoring the head with the lower jaw and then using the leverage to drive the famous canines through their prey with a powerful contraction of neck muscles. Kolponomos was no sabertooth, but Tseng and coauthors thought that the mammal could have used the same strategy to detach mollusks from their beds.

The Kolponomos bite sequence. Credit: Jack Tseng

To find out, Tseng and colleagues took a multi-pronged approach involving virtual models of Kolponomos, Smilodon, and five other carnivorans to examine bone stress during simulated bites and compare shape, adding examination of tooth wear patterns to see how the hypothesis held up. What they found was that Kolponomos fed like no mammal alive today.

Tseng and coauthors were on the mark with their Smilodon suspicion. Despite being distant relatives and feeding on entirely different prey, the lower jaws of both Kolponomos and Smilodon were extremely similar in their anatomy, shape, and response to anchor bite stress. The anchor bite was the key. More than that, the researchers found that even though the teeth of Kolponomos resemble those of sea otters the crushing portion of the extinct mammal’s jaw was actually much more like that of a bear in being stiffer but with less mechanical efficiency. Otters show the opposite condition, indicating that there’s more than one way for a carnivoran to be a shell-crusher as far as lower jaws are concerned. This makes the jaws of Kolponomos a multitool, the front strengthened for prying up shellfish and the back stiffened to crush through those defenses.

So if you were to visit coastal Washington about 20 million years ago, you might have seen something almost like a bear, but not quite like a bear, ambling along the rocky shorelines. Sniffing out a shellbed, the burly carnivore opens its jaws to jam its lower teeth into the colony of clams, biting and jerking its neck. The first shove doesn’t work, but the beast bites again and with another spasm the clam comes free with an audible pop and a little arc of spray as Kolponomos tosses its head back. There’s no hope for the bivalve now – with a swipe of its tongue the mammal shoves the snack to its cheek, and you can hear the shell give way beneath molars flattened through repetition. A quick swallow and the mammal’s snout is back in the shallows, ready to pry out another morsel as well as our preconceived notions about what fossil mammals were really like.

Reference:

Tseng, Z., Grohe´, Flynn, J. 2016. A unique feeding strategy of the extinct marine mammal Kolponomos: convergence on sabretooths and sea otters. Proceedings of the Royal Society B. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.0044

[This post was originally published at National Geographic.]