This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Tyrannosaurus rex – the tyrant king lizard, prize fighter of antiquity, most apex of apex predators, and supremely fluffy destroyer of dino fans dreams.

I have to admit, I’ve enjoyed the tyrant’s shaggy makeover during the last few years. A coat of fuzz only made ol’ T. rex stranger, more like a real animal rather than a Steven Spielberg movie monster. “Let dinosaurs be dinosaurs”, paleontologist Peter Dodson once wrote, and a fluffed-up T. rex was a reminder to do just that and allow dinosaurs to be weird in all their simultaneously scaly and feathery glory.

Naturally, some take a different view.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Stories this week have reveled in the announcement that no, T. rex was not enfluffled after all. Discover’s Gemma Tarlach was especially gleeful, writing:

It’s a good day here at Dead Things: A new study provides a nice big nail in the coffin of the notion that T. rex and its kin ran around all kitted out in feathers. Lovers of old-school, scaly dinosaur renderings, rejoice!

But it’s not quite time to canonize the Jurassic Park T. rex as the standard image of our favorite prehistoric beast just yet. There’s little doubt that our favorite bone-chomper wore fluff. It’s just a question of how much.

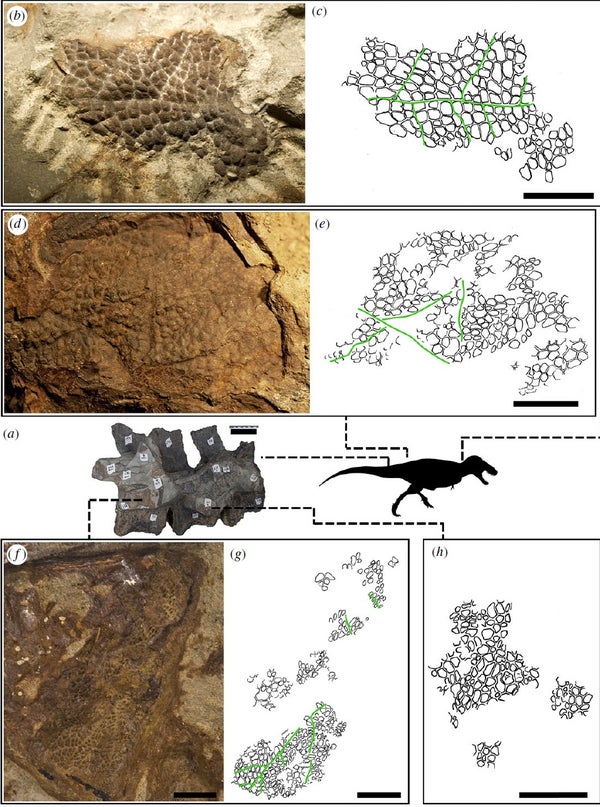

The study in question, carried out by paleontologist Phil Bell and colleagues, surveyed patchy skin impressions from not only Tyrannosaurus itself, but its close relatives Tarbosaurus, Daspletosaurus, Albertosaurus, and Gorgosaurus. These are the carnivores that we typically envision of when we think “tyrannosaur”, complete with big heads and spindly arms. And in each case, the only integument known from these dinosaurs were blotches of scaly skin from areas of the neck, hips, and tail. No signs of fuzz or protofeather showed up.

So this proves the biggest, baddest tyrannosaurs were totally scaly, right? Well, no.

The preservation of scales on tyrannosaurs shows that they had scales, just like any other dinosaurs. But these scraps of ancient skin don’t preclude the presence of feathers for a variety of reasons.

Tyrannosaurus skin patches. Credit: Bell et al 2017

First off, we’ve got to check our assumptions. The presence of fossilized skin can’t be taken as an indication that the preservation of these animals was pristine, or completely represents the entirety of their external appearance. Some dinosaurs we know were feathered are preserved with plumage. Other times they are not. In rare cases both fluff and scales are found. Not to mention that soft tissue remains like patches of skin are not always preserve in their original place. The taphonomy of how skin and protofeathers preserve, or do not, is little known, and the positive presence of skin can’t automatically be taken as an indication protofeathers were absent.

We also have good reason to believe that large tyrannosaurs were fluffier than we know.

Tyrannosaurs belonged to a greater group of theropod dinosaurs called coelurosaurs. Every single lineage in this family – which includes birds – has some kind of protofeather, if not true feathers. Even within the tyrannosaur lineage, there are two earlier animals that unequivocally sport fluff. There’s little Dilong and the 30-foot-long Yutyrannus, both of which were broadly covered in protofeathers. Both were relatively distant relatives of T. rex, and lived tens of millions of years earlier, but they definitively pin fuzz to the tyrannosaur lineage.

What this means for T. rex and company is that protofeathers would have been an ancestral trait. So even if assume for a moment that the new study is correct and the rare patches of tyrannosaur skin really do represent a body surface of scales, not a wisp of feather in sight, it doesn’t mean that feathery integument wasn’t present elsewhere on the body. Those preserved parts are still only patches and we lack a complete picture of the animal. As paleontologist Thomas Holtz and others have pointed out on Twitter, this is like pointing to the scaly leg of a bird or naked head of a vulture and saying the rest of the animal couldn’t possibly be feathered. It doesn’t follow.

And then there’s the elephant defense. The argument goes that a coat of fuzz would have insulated large, hot-blooded tyrannosaurs and made it easier for them to overheat. Therefore, much like elephants, tyrannosaurs would have lost their fluff to keep cool.

There are a few snags here. Experiments with elephants have shown that even without a dense coat of fur, animals their size build up a great deal of heat quickly and often rely on behavioral solutions – like traveling at night, or wallowing in water – to dump heat. Lacking fuzz might not have really saved T. rex very much trouble at its size. And just looking at elephants, they stuff have fuzz! They are not fully covered like a mammoth, yet you can easily spot the hairs their mammalian ancestors gave them. It may have been the same for T. rex. A thick coat of protoplumage might be out of the question, but it’s entirely reasonable to imagine tyrants with tufts and wisps of fuzz along its body. Other theropod dinosaurs, like the comparatively small Juravenator, have already shown such arrangements.

Of course, the only reason this story roared through social media this week is because it’s about T. rex. If the paper in question looked at the merits of fuzz on different, more obscure dinosaurs, it probably wouldn’t have legs beyond the web’s paleo enclave. T. rex is an ambassador to the past, not to mention a celebrity with better brand recognition than any Hollywood superstar, so it’s not really surprising that folks have strong feelings about what this dinosaur looked like. Kids of the 70s through the 90s grew up with scaly terrors. From the early 00s on, it’s been fuzzy. The traditional T. rex is trying to hold its ground against its more ornate replacement.

So here’s where we stand. We know some early tyrannosaurs had both feathers and scales. We also know that the last tyrannosaurs, descended from fuzzy ancestors, had scales on parts of their bodies. That’s as far as the positive evidence goes right now. Despite the conclusions of the new study, totally naked tyrannosaurs seem unlikely. But we still lack a delicate, fine-scale, definitive view of what Late Cretaceous tyrannosaurs really looked like. Any restoration – from totally squamous to poofed up with down – require speculation. So speculate away. We’ve only known T. rex for a little over a century. We still have plenty of time to get to know our favorite bonecrusher, no matter how cuddly it ends up looking.

Reference:

Bell, P., Campione, N., Persons, W., Currie, P., Larson, P., Tanke, D., Bakker, R. 2017. Tyrannosauroid integument reveals conflicting patterns of gigantism and feather evolution. Biology Letters. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2017.0092