This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Spotted hyenas are deadly smart. The giggling, pack-hunting beasts - along with other brilliant creatures like dolphins and ravens - are living proof that primates don't have a corner on enhanced cognitive abilities. They can cooperate with each other to solve problems, deceive their enemies, and use their brains as well as their impressive jaws to make their mark on the African veldt. But when did they gain their impressive predatory intelligence?

A pair of studies published last year by paleontologist Victor Vineusa and colleagues drew from the fossil record to refine how hyena brains changed through the ages. High-definition CT scans of fossil hyena skulls formed the basis for comparison. Even though the soft tissues of the fossil hyenas decayed away long, long ago, the tight fit between brain and skull provides a rough roadmap to brain size, proportion, and anatomy emblazoned inside the cranium. What the researchers found was that the exceptional braininess of today's spotted hyenas was a relatively recent development.

The first study focused on a trio of skulls from Ice Age deposits of the Iberian Peninsula. All belonged to Pliocrocuta - a hyena slightly larger than today's spotted hyena that roamed Europe around 2 million years ago. This was a bone-crusher. The frontal sinuses of Pliocrocuta, Vineusa and coauthors pointed out, reach over the braincase. This is a strange feature among carnivorans - cats don't show this, for example - and it seems to be related to bone-cracking abilities, creating a kind of buffer to deal with the stress of crunching up skeletons.

Yet Vineusa and coauthors doubt that Pliocrocuta was roving around in clans like spotted hyenas. The mammal's brain size and proportions more closely resembled those of today's striped and brown hyenas. These are the living hyenas who more regular scavenge, and, while they are sometimes social, they don't have the complex clan life of spotted hyenas or patrol over such wide areas. It's impossible to know the exact intelligence of an extinct species. It's hard enough for living creatures! But if Pliocrocuta was anything like today's hyenas, it seemed to fall short of the social brain spotted hyenas eventually evolved.

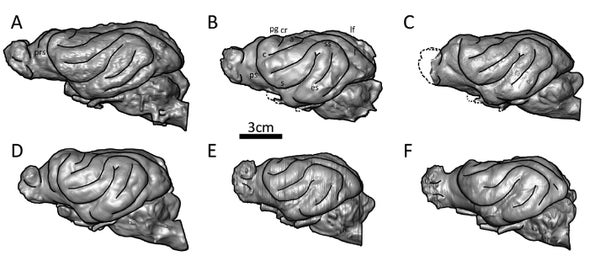

Brains of fossil and living hyenas. A) Crocuta spelaea, B) Crocuta ultima, C) Crocuta ultima, D) Crocuta crocuta, E) Hyaena hyaena, F) Parahyaena brunnea. Credit: Vinuesa et al. 2015

Even species more closely-related to today's spotted hyenas might not have shown the same propensity for forming cooperative clans. In a second study, Vinuesa and colleagues looked inside the heads of the cave hyena, Crocuta spelaea, from Italy and Crocuta ultima from China. Naturally the anatomy of their brains was more closely related their living spotted hyena relative, but, the researchers found, there were some important differences in the front portion of the brain. In short, the part of the brain related to thought and complex behavior wasn't as expanded in the fossil species as in today's spotted hyena. Similar to the older Pliocrocuta, that portion more closely resembles seen in today's striped and brown hyenas.

Spotted hyenas only recently gained their peculiar intelligence. The first of their genus - the earliest Crocuta - evolved in Africa between 3.85 an 3.63 million years ago. From there, Crocuta species eventually moved into Asia by 2.2 million years ago and Europe by 800,000 years ago. These included the species from Italy and China included in the new study. As far as Vinuesa and colleagues can discern though, Crocuta crocuta - the spotted hyena - didn't start to get brainy until about the time their species expanded into Eurasia around 63,000 years ago. That's practically yesterday.

Figuring out why spotted hyenas got so smart is more problematic than figuring out the history of our own cognition. The social brain hypothesis suggests that complex, gregarious behavior would drive bigger and more intelligent brains. But there are mitigating factors on this. For example, smarter brains might be tied to better food - spotted hyenas eat more fresh meat than striped or spotted hyenas - and greater intelligence is also useful in navigating wide swaths of habitat and having the behavioral flexibility to react to new situations. Parsing which of these factors, or combination of factors, was key is something that's still difficult to do.

If you were to go back to the Pleistocene, then, you might not have seen clans of cave hyenas squaring their paws at bands of Neanderthals. The older Ice Age hyenas probably weren't just bigger versions of their modern relatives and had a behavioral repertoire all their own. The spotted hyena is something newer, and sharper on this Earth, and I hope their brain power keeps them around for millions of years to come.

References:

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Vinuesa, V., Iurino, D., Madurell-Malaperia, J., Liu, J., Fortuny, J., Sardella, R., Alba, D. 2015. Inferences of social behavior in bone-cracking hyaenids (Carnivora, Hyaenidae) based on digital paleoneurological techniques: Implications for human-carnivoran interactions in the Pleistocene. Quaternary International. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2015.10.037

Vinuesa, C., Madurell-Malapeira, J., Fortuny, J., Alba, D. 2015. The endocranial morphology of the Plio-Pleistocene bone-cracking hyena Pliocrocuta perrieri: Behavioral implications. Journal of Mammalian Evolution. doi: 10.1007/s10914-015-9287-8