This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

African elephants are sturdy beasts. The largest of these behemoths tips the scales at over 13,000 pounds of flesh and bone, and this presents a rather hefty challenge when elephants pass away. The moment the beast falls, a diverse deconstruction crew gets to work.

There’s an entire science devoted to the afterlives of organisms. It’s called taphonomy, usually summed up as “what happens to an organism between death and discovery.” Why fossil plants are beautifully preserved in one place but not another or why one dinosaur is a complete skeleton while another is just a pile of bone fragments are the kinds of puzzles investigated by this science. The key to understanding those ancient conundrums, though, is looking to what happens to modern species, including the largest land mammals on the planet.

Paleontologists have been carefully documenting elephant afterlives for decades, but one of the more recent studies focused on a postmortem pachyderm observed by paleontologist P.A. White on a lakeshore in Zambia’s Kafue National Park. What killed the elephant isn’t known, but the body was found on the day on October 10th, 2010. From there White watched what happened to the carcass every day for two weeks, then twice weekly for the next month, and then intermittently until September, 2011. At the end of each visit, White would brush away the tracks and scats of visiting animals to get a better idea of who was coming by the body when he wasn’t looking.

The elephant during early stages of decomposition. Credit: White and Diedrich 2012

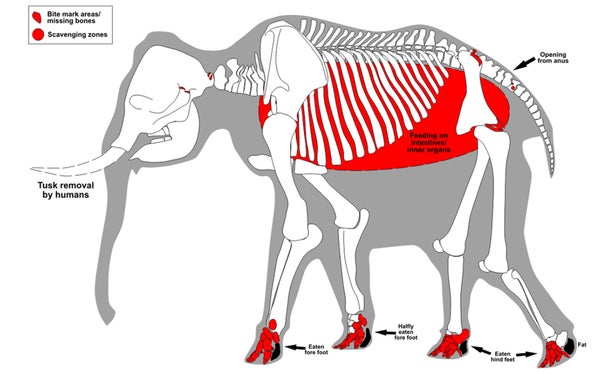

While the decomposition of an entire elephant might seem like a chaotic process, dictated only by nature itself, there was a defined order to the proceedings. As is their wont, big carnivores were the first to arrive. Lions, soon followed by spotted hyenas, pulled the earliest shifts, and they went for the trunk, viscera, and, apparently of special interest to the hyenas, the feet. After two weeks being exposed, White and study coauthor C.G. Diedrich later wrote, “the elephant carcass was largely desiccated and all easily accessible soft tissue have been removed by small scavengers” including side-striped jackals, civets, genets, and vultures. By then the elephant was little more than dried-out hide suspended on a framework of remaining bones.

A little rain can freshen up even the driest carcass, however. The first rain of the wet season moistened the elephant just enough to reinvigorate the interest of local spotted hyenas who gnawed on the rather spare remains over four days. By the next month, however, the rains jumbled up what was left. Between December and April, during Zambia’s wet season, the elephant’s remains were submerged by a shallow lake that filled the divot where it died. When it was visible again in May, the pachyderm’s bones were scattered through the tall grass, and that’s the way it stayed. By September of 2011, nearly a year after it died, the elephant had been changed into a mess of bones strewn across the ephemeral lakeshore.

So what does this all mean? While watching an elephant fall apart may seem like a rather tedious pastime, studies like this can help paleontologists better understand what happened in the deep past. Big carnivores like lions and hyenas are an important part of carcass breakdown, for example, cutting through the thick hide of the elephant and opening up the juicy bits smaller scavengers later pick from. It’s also relevant to our past, too.

Multiple fossil sites through the Old World show the presence of humans and prehistoric carnivores at elephant carcasses. A paper published just last year, for example, places both prehistoric people and the giant hyena Pachycrocuta at the same elephant carcass in Spain, with humans moving in fast to cut off meaty limbs to consume away from the competing jaws of the bestial carnivores. The rate at which modern elephants break down only reinforces the idea that our ancestors would have to move quick if they wanted a meaty meal, within days of death if they wanted anything more than desiccated hide and bone. Dining at an elephant carcass is a first come, first-served affair.

Reference:

White, P., Diedrich, C. 2012. Taphonomy story of a modern African elephant Loxodonta africana carcass on a lakeshore in Zambia (Africa). Quaternary International. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2012.07.025