This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Fossiling does a body good. At least that’s what I told myself as I tied my boots and pulled a slicker over my shoulders to shield myself from the drizzle coming down on the stretch of Charmouth shoreline. The cold I had been fighting since I left London called for bedrest, not soaking myself on England’s southern shore, but I had specifically allotted two days to searching the Jurassic stomping grounds of legendary paleontologist Mary Anning. There was no way I was staying under the covers. Wrapped up as best as I could manage, I pulled the hood over my baseball cap, sneezed, and started off with my wife Tracey along the beach.

I wasn’t expecting to find anything right away. At any fossil site, especially an unfamiliar one, it takes a little while to develop a search image – the recognition of telltale characteristics that makes fossils pop out from the background. But even though I was more accustomed to prospecting places far less saturated than the beach, I figured that luck would be with me. The stretch of sand Tracey and I walked along had given up fossils like a beautiful skeleton of a 191 million year old Scelidosaurus – one of the earliest armored dinosaurs – as well as reptilian fish mimics called ichthyosaurs and countless invertebrates, such as the coil-shelled ammonites. That’s really all I wanted, to find a little Jurassic coil resting on the sand.

It took about an hour and a half before we started finding anything. But once Tracey and I started to take notice of the sparkly little ammonite shells, shaded in gold thanks to the pyrite that was also slowly destroying them, they seemed to be everywhere. Soon the goal wasn’t to find the Jurassic whorls, but to spot the best ones. And in the process, at the edge of the receding water, I stumbled across a type of fossil I hadn’t held since my childhood. It was about the size and shape of a half-burnt cigar, and if I hadn’t been all stuffed up I might have attempted a Groucho Marx impression. I was given a little bagful of fossils just like these when I was a kid from a family friend I can only dimly remember, but I never forgot what these shells were.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

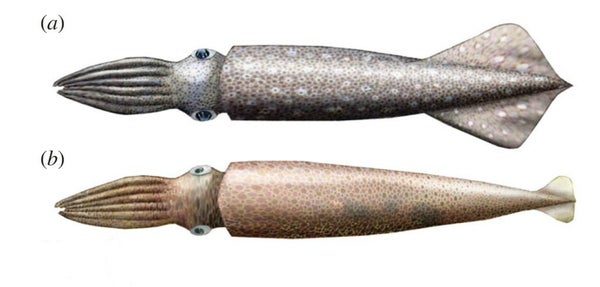

They’re called belemnites. To me that name has always been synonymous with broken, wave-rolled pieces of what used to be part of the cephalopod’s internal skeleton. And, as museum displays and illustrations of ichthyosaurs feasting upon them taught me, their outer appearance was pretty much like that as a common squid that you might find frozen in the seafood section of the supermarket.

Despite my early introduction to the belemnites, however, I never bothered looking into what was known beyond the bullet-shaped guards I already knew about. My vertebrate bias blinded me. As it turns out, some truly exceptional specimens have not only revealed the form of the belemnites, but how they lived in the oceans of long ago.

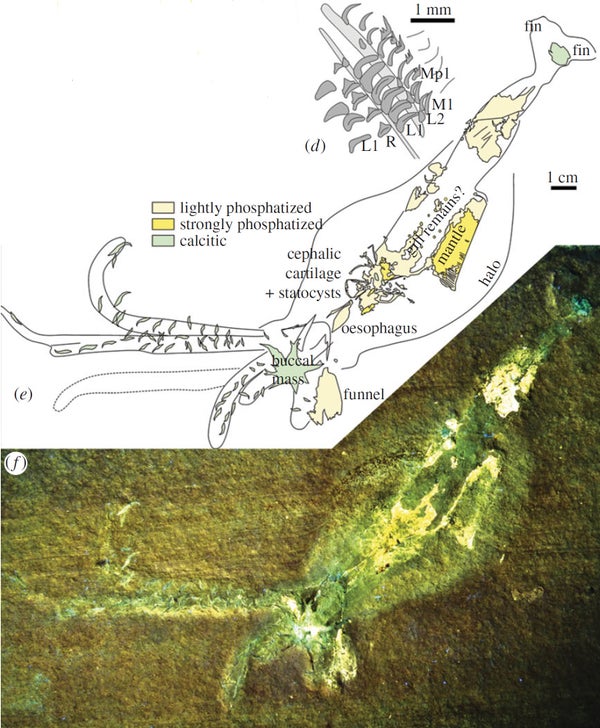

An exquisite Acanthoteuthis. Credit: Klug et al. 2016

Earlier this year, in Biology Letters, fossil cephalopod expert Christian Klug and colleagues described a pair of special belemnitid fossils found in the Late Jurassic limestone of Germany. On a superficial level these specimens of Acanthoteuthis look like smushed banana peels, but, under UV light, they truly shine. Funnel, esophagus, the buccal mass that held the pinching beak, and even that statocysts that helped these invertebrates know where they were in the water are all intact.

The preservation is so delicate that the two specimens can easily be told apart by their fins. One Acanthoteuthis has broad fins jutting from the tip of its streamlined body while the other is more minorly-equipped with itty bitty flappers. And the fact this pair of ten-armed cephalopods have fins at all confirms what paleontologists suspected, but were unable to confirm, for almost a century. Indentations on the internal skeleton suggested the presence of these propulsive structures, but soft-tissue support remained lacking. Now, as Klug and coauthors report, we can be sure that belemnitids sped around the underwater world with the help of fins.

And speed they did. Belemnitids have often been thought of as nektonic animals – that is, ones that lived their entire lives actively swimming in the water column. The fins fit this picture, but so do the statocysts that let the cephalopods orient themselves in the water. “The statocysts of fast-swimming buoyant squids are commonly larger than those of non-buoyant ones,” Klug and colleagues write, and the organs in Acanthotheuthis are more consistent with a life zipping around in midwater, swarming into the great mass of food that allowed the fantastic marine reptiles of the Jurassic to thrive and live as large as they did.

Reference:

Klug, C., Schweigert, G., Fuchs, D., Kruta, I., Tischlinger, H. 2016. Adaptations to squid-style high-speed swimming in Jurassic belemnitids. Biology Letters. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2015.0877

[This post was originally published at National Geographic.]