This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Smilodon cut a striking profile. While the great beast’s skull is readily recognizable as a variation on the theme of cat, the mammal's fearsome upper canines would have given the carnivore a bit more of an edgy appearance. But lately there’s been an artistic trend to cover up those fangs with loose flaps of flesh. Did Smilodon and its relatives have funky bulldog faces?

Even though smooshy-lipped sabercats are popular right now, the idea isn’t entirely new. In 1969 paleontologist G.J. Miller published an obscure paper arguing that Smilodon looked very, very different from traditional restorations that depicted that cat as something like a lion with ludicrously-long canines. In Miller’s view, Smilodon had a pug nose, low-set ears, and a long, fleshy lip line.

Miller's Smilodon. No thanks. Credit: Antón et al. 1998

Some of Miller’s reconfigured features were based on anatomy – such as the placement of the nasal bones and the sabercat’s prominent sagittal crest at the back of the skull – but the loose, floppy-looking lips were a functional consideration. Sabercats like Smilodon were able to open their jaws extremely wide in order to clear those deadly upper canines, and such a gape, in Miller’s view, required a longer lip line. On top of that, Miller proposed, fitting food into the mouth sideways would also be easier with greater space for clearance. So while Miller’s restoration still left the canines exposed, his 1969 view of the cat is the droopy-looking forerunner to the current trend of making Smilodon look like it was hit in the face with a frying pan.

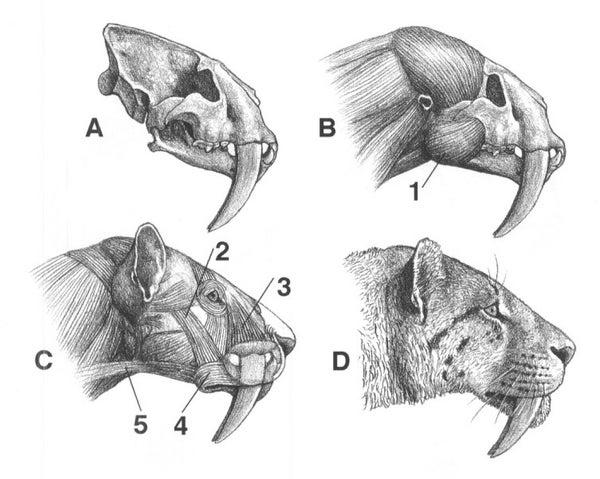

No one has found a Smilodon with facial soft tissues intact. It’s entirely possible that the carnivores looked different from how we expect. But, given that finding a pristinely-preserved sabercat is highly unlikely, we have to turn to modern cats for clues. And that’s precisely what paleoartist Mauricio Antón and colleagues did in a 1998 reappraisal of Miller’s hypothesis.

Drawing from the anatomy of living cats, Antón and coauthors couldn’t find any anatomical backing for Miller’s dog-like sabertooth. The positions of the nose and ears in Smilodon, the researchers found, likely followed the same arrangement as in modern cats, the sabercat not being markedly different in the anatomy of its nasal bones or the osteological opening to the ear canal. As for that long lip line, Antón and colleagues noted that this crease always ends to the front of the masseter – a major muscle in closing the jaw. The bony landmarks on the Smilodon skull give away where this muscle sat, and its position dictates a short, typically cat-like lip line.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Step-by-step restoration of Smilodon. Credit: Antón et al. 1998

Smilodon didn’t need saggy lips, anyway. Miller had assumed that opening the jaw wide would “seriously tax” the elasticity of the flesh around the mouth. Yet, Antón and coauthors wrote, all you have to do is watch a cat yawn to see this isn’t true. “When modern cats yawn, and once the maximum gape of about 70º in the living animal (as estimated directly from numerous photographs and video stills) has been reached, the animals often grimace, further exposing their check teeth and gums and showing very clearly that the elastic limit of the tissues has not been reached.”

There’s simply no evidence for dog-faced sabercats. In fact, the clues preserved on their skulls and the anatomy of their living cousins is balanced against the idea. And while there’s been some argument that big lips would have been helpful in protection or hydration – as there has been suggested for dinosaurs, too – there are sabertoothed mammals alive today that flash their canines to the world without extraneous protection. Male musk deer and muntjacs, for example, have elongated canines that remain at least partly exposed at all times. They use their fangs for combat, rather than slicing the throats of prey, but it’s still another wrinkle in favor of traditional sabercats.

This isn’t to say that restorations of lippy sabercats are bad. I wrote this post because I’ve been asked about the trend more than once and wanted to create a reference on the topic. Paleoart always requires imagination, and the discipline has often leaned more towards the conservative. It’s heartening to see paleoart enter its experimental phase, moving beyond simple flesh-on-bones restorations. But, in this case, there's no anatomical backing for saggy-faced sabercats, and I have to admit that I’ve never been a fan of the trend. I’m glad to say, as far as our current knowledge goes, Smilodon looked sharp.

Reference:

Antón, M., García, R., Turner, A. 1998. Reconstructed facial appearance of the sabretoothed felid Smilodon.Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.1998.tb00582.x