This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

In North America, at least, the Early Jurassic is a mysterious time. There are plenty of rocks of the right age to document the comings and goings of species as the Age of Dinosaurs kicked into high gear. Remnants of prehistoric sand dunes capture the tracks and traces of dinosaurs, arthropods, protomammals, and more, for example, in localities from the East Coast to the middle of the Four Corners. But if you’re looking for bones, the Early Jurassic can be a heartbreaker.

Sauropodomorphs are a fine example of this frustration. These dinosaurs were the relatives and forerunners of familiar giants like Brontosaurus and Brachiosaurus. They were often awkward, gangly creatures who stood cantilevered on two legs or with a flexed quadrupedal posture, their long necks carrying small heads with grins brimming with leaf-shaped teeth. And in the whole of North America’s Early Jurassic record, there are only three.

One of these sauropodomorphs, Anchisaurus from Connecticut, was an early find and named in 1885. Another, Seitaad from Utah, was named in 2010. And then there’s Sarahsaurus, found in Arizona’s Kayenta Formation and first described in 2011. These dinosaurs didn’t overlap in time. Each lived during separate slices of the Early Jurassic, Sarahsaurus temporally slotting in between the other two. And this raised a Jurassic mystery that’s answered in a new study on Sarahsaurusby paleontologists Adam Marsh and Timothy Rowe.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

A little context is needed here. Dinosaurs originated about 235 million years ago, in the Triassic, but were pretty marginal ecological players until close to the close of that period. Sauropodomorphs found in modern day South America, Africa, Asia, and Europe from the Late Triassic were some of the first giant dinosaurs anywhere. But no Late Triassic sauropodomorphs have been found in North America. The only North American members of this group show up after the 200 million year mark, following a mass extinction that cleared the way for dinosaurs to take over major ecological roles, all of them Early Jurassic in age. This raises the question of whether Anchisaurus, Seitaad, and Sarahsaurus form their own evolutionary group that evolved within North America from some unknown ancestor, or if they represent immigrations from elsewhere.

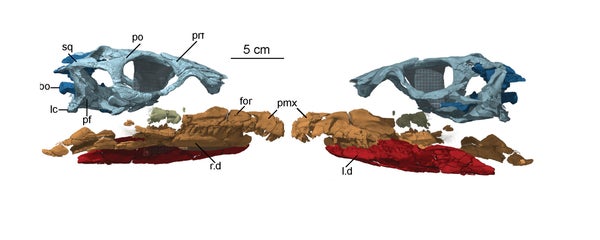

Marsh and Rowe address that question through a new analysis of Sarahsaurus fossils, newly-prepared bones and CT scans of those fossils allowing a more complete anatomical guidebook of this dinosaur’s skeleton. From there, Marsh and Rowe were able to compare Sarahsaurus to other sauropodomorphs from North America and abroad to hypothesize how these dinosaurs are related to each other.

The emerging picture is that Sarahsaurus isn’t as closely related to Seitaad and Anchisaurus as geography might lead you to expect. Sarahsaurus seems to group closely with sauropodomorphs from South Africa, South America, China, and Antarctica rather than with other dinosaurs of its kind found in North America.

Considering the absence of sauropodomorphs in the Late Triassic and the fact the three North American species were not closely related, then, Marsh and Rowe propose that there either was some barrier that affected dinosaur dispersal into North America from elsewhere or that the process took longer than might be expected. It may be that the mass extinction that shook the Late Triassic cleared the way for dinosaurs to disperse and plow new niches in North America, Marsh and Wrote write, and that this hadn’t been possible while ancient crocodile cousins were the dominant vertebrates on land during the Triassic. Instead of ruling the world from the outset, dinosaurs were opportunists who were ready when their lucky break finally came.