This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

When Michael Crichton wrote Jurassic Park, he was thinking small.

Don’t get me wrong. The idea that prehistoric insects might preserve Mesozoic dino DNA was pretty ingenious and forever changed scifi. But he was mostly focused on a mechanism for genetic tatters to get to the present day. I don’t think Crichton, or anyone else, expected half a dinosaur would be encased in amber.

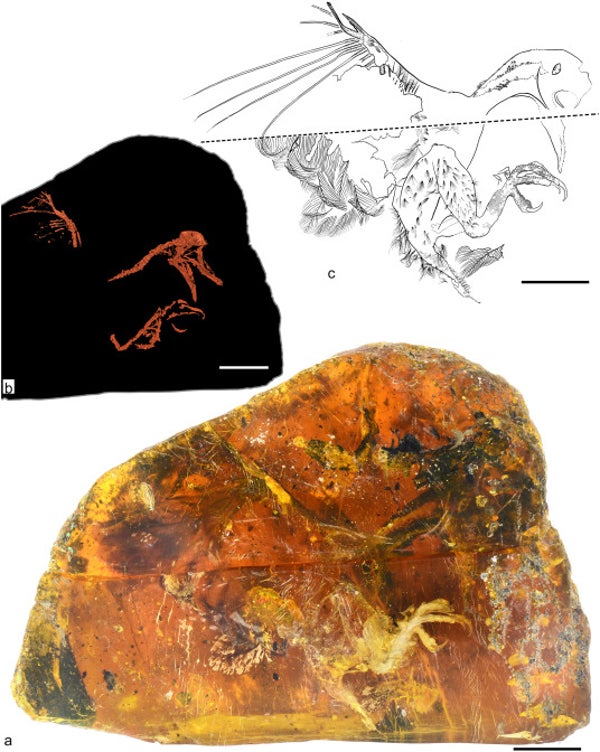

To be fair, the dinosaur isn’t even close to the scale of the giants in Jurassic Park. You could hold it in the palm of your hand. But, as described by paleontologist Lida Xing and colleagues, this amber-bound dinosaur is a little treasure. Ensconced in the 98 million year old tomb is what remains of a Cretaceous bird.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In technical terms, the little chick was an enantiornithine. This was the lineage of avian dinosaurs that proliferated during the Cretaceous, some of which retained teeth and wing claws that made their ancestry immediately apparent. And even though parts of enantiornithines had been found in amber before, this chick is the most complete look we’ve ever been granted at the life appearance of a dinosaur.

The fossil chick in amber. Credit: Xing et al 2017

Peering at the blob of amber, the foot is immediately what stands out. It seems to be reaching for you, the tiny scales of the foot preserved in stunning detail. This alone would be amazing, a literal window into the Mesozoic. But then there are the feathers.

The fossil, simply known as HPG-15-1, bears the most complete example of young enantiornithine plumage paleontologists have ever seen. And it’s weird. Even though the chick is partly covered by simple protofeathers – much like the down you’d expect on modern baby birds – other feathers are more like the contour feathers you’d find on the bodies of adult avians. In other words, these birds were not just like their living avian relatives – their hatchlings, at least, had an odd combination of feathers that makes them different from both their Velociraptor-like ancestors and the scrub jay screeching in the front yard as I write this.

We don’t need a genetic engineering firm to bring ancient dinosaurs back. The fossil record contains more wonders than we can even imagine. To borrow the tagline from Jurassic Park’s first sequel, something has survived.

For further analysis, check out paleornithologist Hanneke Meijer’s post.

Reference:

Xing, L., O’Connor, J., McKellar, R., Chiappe, L., Tseng, K., Li, G., Bai, M. 2017. A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine (Aves) hatchling preserved in Burmese amber with unusual plumage. Gondwana Research. doi: 10.1016/j.gr.2017.06.001