This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The year 2015 will go down in the annals of vision research history as a watershed moment. in which the internet discovered an entirely new visual phenomenon—a dress that half of the world saw as black/blue and the other half as white/gold. Had it not been for social media and its particular way of framing conversations around shared crowd-sourced images, this peculiar visual puzzle might have remained unknown.

The idea that an object could look one color under one set of lighting conditions, and another color under another set of lighting conditions, was not new. What was unique about The Dress was that the same image, under the same exact viewing conditions, looked very different to different people. The color ambiguity only became evident when half of the viewers disagreed with the other half, which is probably why social media was so pivotal in its discovery.

Vision scientists went bananas. Was it an artifact of different device screens? Did it have to do with gender, culture, education, or some other categorization of brain and persona? How many people—exactly—saw the image one way or the other? This was a dress that sailed a thousand ships. The vision science field eventually verified that the phenomenon was definitely real and not an artifact of viewing conditions. Though the precise underlying mechanisms remain unknown, even now.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Similarly ambiguous color images followed the dress, but a main obstacle to figuring out how and why such effects existed was that all of the images were flukes. They were accidental happy snaps created by internet picture-posters. Scientists could not intentionally create new and carefully controlled examples for deep study in the lab. Until now.

As we reported in our most recent Illusions column in Scientific American: MIND, the laboratory of Pascal Wallisch, at New York University, has now successfully created new color-ambiguous stimuli, based on the theory that this kind of illusion is due to our accumulated prior life experience with the specific objects in the images. That is, our prior visual experience with specific objects biases our brains to interpret an ambiguous image one way or another, based on how we typically experience them in life.

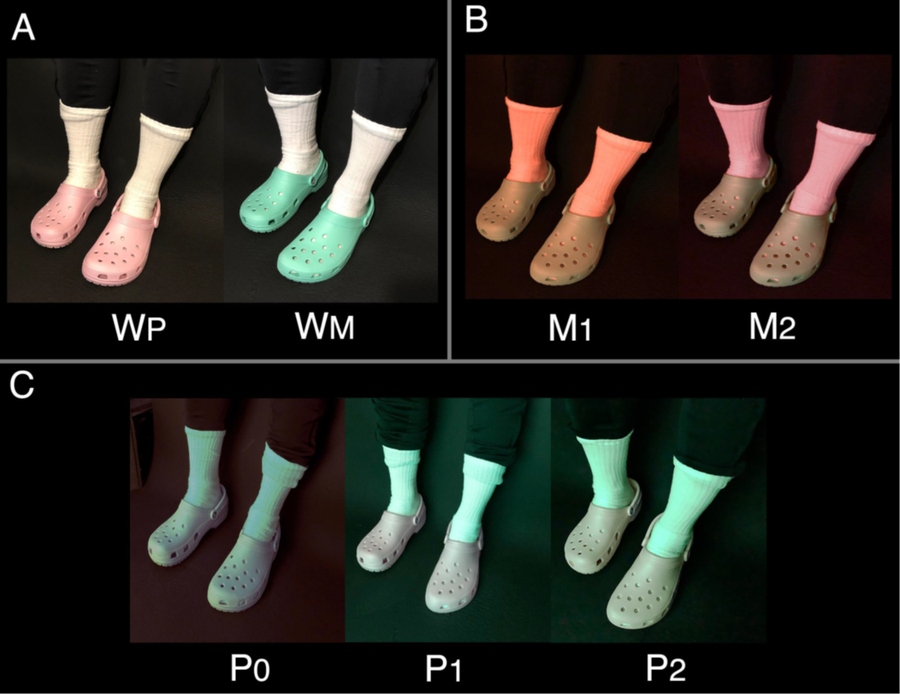

Wallisch and his team chose to test their theory with Crocs: objects that come in lots of colors (28 to be exact), and which most—if not all—study participants would be familiar with. Specifically, the researchers put two different colors of Crocs side by side, while making them appear nearly identical to each other under opposing lighting conditions. The used pink and mint (a shade of green) Crocs and made them both appear gray by varying the lighting conditions: pink Crocs were viewed under green light, and mint Crocs were viewed under pink light. Thus, viewers could interpret the Crocs as being gray—despite that they were pink or mint when viewed under white light—depending on what color they assumed the light source of the scene to be, using clues from the colors of surrounding objects, which were also illuminated under the same special lighting.

In Panel A of the figure below, you can see two pairs of Crocs under white light. Panel B shows just the mint Crocs under two shades of pinkish light, and Panel C shows the pink Crocs under three shades of green light. Notice that all the Crocs appear grayish under colored lights, and that the color of the light source can be inferred from the color of the tube socks. But—and this is critical—this inference is only true if you believe that tube socks are usually white (i.e. because of your past experience with tube socks). This is the basis for the study's main results. When subjects thought the tube socks were white, they tended to see the light source as colored, and so their visual systems consequently interpreted that the Crocs were also under the same light source and were thus colored as either mint or pink. On the other hand, when observers saw the tube socks as intrinsically colored (not white), they tended to see the light source as white, and they interpreted the Crocs as gray. The researchers questioned the participants about their past experience with socks, and found that people who had previously worn white tube socks (a commonly owned article of clothing) were statistically more likely to interpret the socks as white under colored light, rather than gray under white light, and vice-versa.

A) WP: pink Crocs under white light. WM: mint Crocs under white light. B) Mint Crocs under two shades of pink lighting. C) Pink Crocs under three shades of green lighting. Credit: Pascal Wallisch

It follows that your experience with objects biases how you interpret their color under ambiguous lighting conditions. This discovery may be central to understanding color ambiguity illusions, and more generally, color perception.

Check out the 1-minute YouTube movie created by Wallisch and his collaborator Michael Karlovich for more examples and information about this perceptual effect.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ne4exGYx_fo

Further Reading

Pascal Wallisch and Michael Karlovich. Disagreeing about Crocs and socks: Creating profoundly ambiguous color displays. PsyArXiv Preprints. (2019) https://psyarxiv.com/zpqnv/

Susana Martinez-Conde and Stephen Macknik. A Pair of Crocs to Match the Dress. Scientific American Mind 31, 1, 35-36 (January 2020) doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0120-35 https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/a-pair-of-crocs-to-match-the-dress/

Stephen Macknik. The Science Ball Where Everybody Wore the Same Dress. Scientific American Blogs. (June 14, 2015) https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/illusion-chasers/the-science-ball-where-everybody-wore-the-same-dress/

Stephen Macknik, Susana Martinez-Conde and Bevil R. Conway. (2015). Unraveling “The Dress.” Scientific American Mind, 26, 19–21, doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0715-19.https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-the-dress-became-an-illusion-unlike-any-other

Stephen Macknik. The Current Biology of the Dress. Scientific American Blogs. (May 16, 2015) https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/illusion-chasers/the-current-biology-of-the-dress/