This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The Anderson-Winawer Illusion

Credit: © 2005 The Nature Publishing Group

Our new Illusions article in the November 2016 issue of Scientific American Mindfeatures a brain conundrum as old as science itself. Galileo Galilei, who many view as the first scientist of the modern age, could not trust his own eyes. He noticed that when he viewed a moon of Jupiter with the huge planet in its background, the moon appeared smaller than when he viewed the same moon as a bright spot against the black night sky. Leonardo Da Vinci, too, noticed that precision of vision varied with darks versus lights (though he noticed the effect on the painter’s canvas). Hermann von Helmholtz, the venerable German Physicist-Physician, recognized that the effect must have something to do with the brain, as he pondered the Irradiation Illusion.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

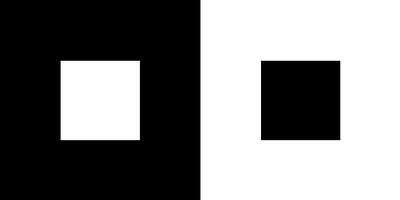

The Irradiation Illusion. Helmholtz Noticed that a square, when viewed white-on-black, appeared larger than when viewed black-on-white.

In the article we describe some of the optical and neural effects that contribute to the superior size of light against dark in our eyes, as well as related brightness effects, such as in the illusion from Barton Anderson (University of Western Australia) and Jonathan Winawer (New York University) (see moving moon image above). We also discuss the neural underpinnings of these effects recently discovered by the labs of Jose-Manuel Alonso at SUNY College of Optometry, and David Fitzpatrick at the Max Planck Institute in Jupiter Florida, and the role they play in our everyday perception.

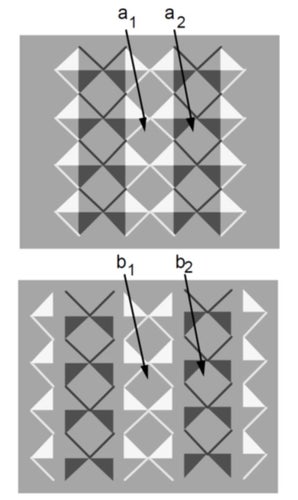

But these contrast effects do not tell the whole story. The context of how light and dark interact across space matters too, as Edward Adelson’s (MIT) incredible Argyle family of illusions show (below). Here, we see that the a diamond shaded in gray will appear light or dark depending on its surround, as well as the distance to the surround.

Edward Adelson SCIENCE • VOL. 262 • 24 DECEMBER 1993

Contrast Is Not Enough

Although contrast is critical to vision, Adelson demonstrates here that there are other unexplained ways that an object’s surface properties affect how we see light and dark. Adelson’s Argyle Illusion reveals that diamonds a1 and a2 appear very different in brightness although they are identical, whereas b1 and b2 appear more similar. The only difference between the top and bottom image is the gap between the vertical light and dark patterns, which for some unknown reason destroys the appearance of shading in the bottom image.