This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Here’s a question I’d like you to answer as quickly as possible, without overthinking it: If you could have the superpower of your choice, what would it be?

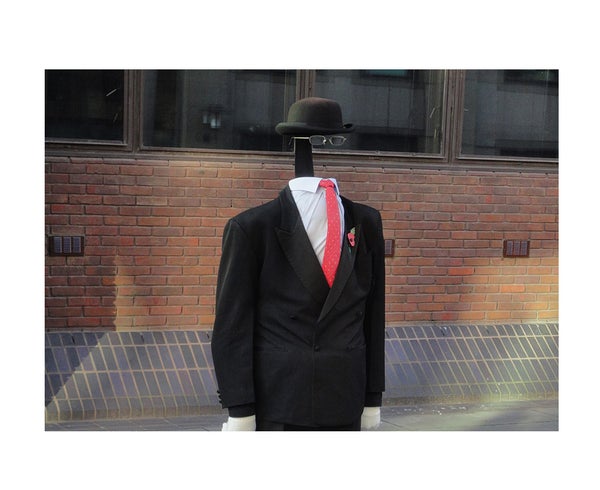

Perhaps you chose super strength, or the power to fly like Superman, or being able to control people’s minds. But I suspect that more than a few of you have gone with invisibility: the ability to see without being seen.

In fact, invisibility has captured human imagination for a long time. Myths and stories in which the hero gains access to this gift (and occasional curse) abound: the goddess Athena provided demigod Perseus with a cap of invisibility, which allowed him to sneak up on Medusa and slay her. Gyges of Lydia, as told by Plato in his Republic, entered a cave to discover a magical golden ring that allowed him to become invisible at will. The One Ring, stolen by the hobbit Bilbo in J.R.R. Tolkien’s mythology, is also a magical ring of invisibility. And in the Harry Potter universe, the Cloak of Invisibility renders its wearer fully and instantly invisible.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Such magical artifacts may not be constrained to fantasy scenarios for long: within the last few years, several groups of researchers have started to develop cloaking devices to render objects invisible, based on light-bending optics, metamaterials, and digital methods.

Even though cloaking technology is not yet ready for public consumption, recent research indicates that most of us can experience an invisibility of sorts.

The problem is, it’s all in our minds.

In a study published last December in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Erica J. Boothby, Margaret S. Clark, and John A. Bargh of Yale University reported a phenomenon they named “The Invisibility Cloak Illusion:” Our incorrect belief that we observe others more than they observe us.

Boothby and her colleagues conducted a comprehensive set of studies aimed at characterizing this illusion, as well as the reasons behind it.

The team found that people feel relatively invisible as they go about their daily lives. That’s an impossibility, for obvious reasons: on average, a given person will not observe others more than they themselves are observed. Yet, the Invisibility Cloak Illusion persisted in many different research scenarios, including both social situations among friends, and among strangers situated in one’s vicinity. The authors concluded that the illusion results from the combination of two incorrect beliefs: that we are more observant than others, and that we are less observed than the people around us.

Potential causes for these false beliefs include the fact that we have first-person access to our own thoughts (unlike to other people’s) and that social norms compel our neighbors to pretend to be engrossed on something else if it looks like we might catch them watching us (a phenomenon that has been dubbed ‘civil inattention’). Whatever the reasons, Boothby and her colleagues advise that ‘However irresistible this sensation [of being invisible] may be, it is not to be trusted.’

So now you know. Ever felt you’re being watched? It’s not paranoia if it’s real.