This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

I don’t usually wear makeup, so the few times a year I put it on for a special event, my children tend to comment on it. Some years ago, when my 11-year old must have been 3 or 4, I was getting ready for some fancy dinner, so in addition to my evening attire, I had full makeup on. As I was saying my goodbyes and giving last-minute instructions to our babysitter, my son took a long, stunned look at me, and exclaimed: “Mommy, you’ve turned into a girl!” Which I took as high praise. I remember thinking at the time that what my kid was trying to express was that, with makeup on, I looked noticeably younger than my regular, everyday self.

It turns out that I was correct, according to a new study published in the British Journal of Psychology by Richard Russell of the Department of Psychology at Gettysburg College, in collaboration with researchers from CHANEL Fragrance & Beauty Research & Innovation.

Prior research had established that makeup makes faces look more physically attractive, but the effects on makeup on age perception had remained largely unexplored. Russell and his collaborators set out to determine how wearing makeup affects perceived age on female faces.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

To find out, the team first recruited 32 women in four different age bands: approximately 20, 30, 40, and 50 years old. Each woman was photographed with no makeup, and then after being made up by a professional makeup artist (in different makeup conditions, including “natural” and “intense”), under carefully controlled photographic and lighting conditions. Next, one hundred and thirty-two female participants viewed all the photos and rated each face for attractiveness (on a 0 to 100 scale) and estimated age (from 10 to 70 years old).

Whereas makeup made faces of all ages look more attractive, its effects on apparent age were more complex: middle-aged faces looked younger with makeup on, 20-year old faces looked older with makeup, and 30-year old faces looked their real age whether wearing makeup or not. In addition, makeup applied only to the skin and eye region had a more significant effect on age perception than make up applied to just the skin and lips.

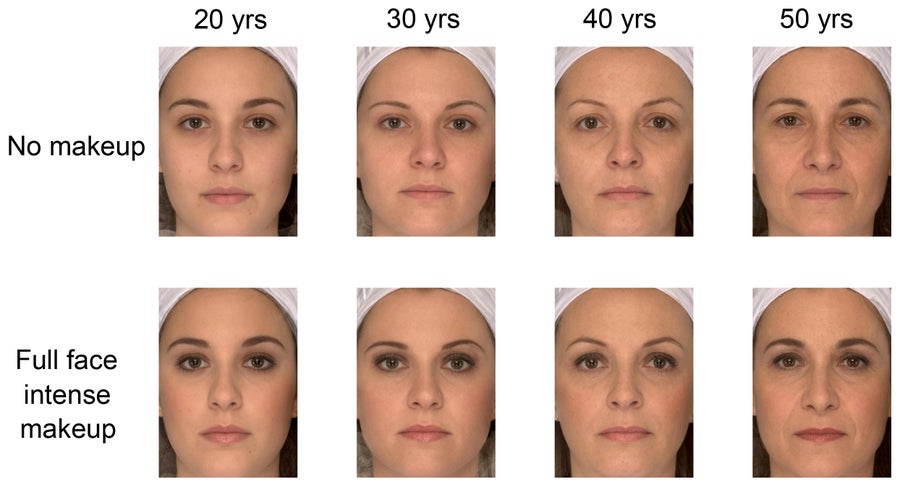

Faces of different ages, with and without makeup. Credit: Richard Russell

The faces displayed above are age-band composites (morphed averages) of the actual faces used in the research. The images all have even skin because of the averaging process, which obscures the skin-evening effect of makeup, said Richard Russell, the study’s lead author. “I find that the faces in the top row (no makeup) appear to have greater variation in age than the faces in the bottom row (full face intense makeup),” Russell added. “To put it another way, the images on the top corners look more different in age than do the images in the bottom corners. This kind of flattening of the age range with makeup is what we [discovered]—makeup makes younger women look older but makes older women look younger.”

According to the researchers, make up accentuates three visual features that we associate with youth: skin evenness, facial contrast (between features such as the eyes and lips and the rest of the face), and facial feature size (more youthful faces have relatively larger eyes). Thus, it made sense that by manipulating these aspects, makeup made the older faces look younger. But this explanation does not account for why makeup should make the youngest faces look older, which the scientists were surprised to discover.

One potential answer is that, in our society, we connect makeup use with adulthood, causing us to perceive women that are near the threshold of adulthood as older that their years when wearing makeup. Taken together, the study’s results suggest that makeup affects age estimation both via bottom-up routes (by altering facial contrast, facial feature size, and skin homogeneity), and also through top-down routes related to people’s implicit consideration of social norms concerning makeup use.

The study’s authors remarked on the practical application of their results, especially concerning ageist discrimination in the workplace, which women are more likely to experience than men. Older women encounter considerable entry barriers in many professions, but on the flip side, women that look too young can be regarded as less competent. Women’s ability to decrease or increase their perceived age with makeup could result in professional benefits, by giving them a an edge in a biased work environment.