This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

The man and the woman sat down, facing each other in the dimly illuminated room. This was the first time the two young people had met, though they were about to become intensely familiar with each other—in an unusual sort of way. The researcher informed them that the purpose of the study was to understand “the perception of the face of another person.” The two participants were to gaze at each other’s eyes for 10 minutes straight, while maintaining a neutral facial expression, and pay attention to their partner’s face. After giving these instructions, the researcher stepped back and sat on one side of the room, away from the participants’ lines of sight. The two volunteers settled in their seats and locked eyes—feeling a little awkward at first, but suppressing uncomfortable smiles to comply with the scientist’s directions. Ten minutes had seemed like a long stretch to look deeply into the eyes of a stranger, but time started to lose its meaning after a while. Sometimes, the young couple felt as if they were looking at things from outside their own bodies. Other times, it seemed as if each moment contained a lifetime. Throughout their close encounter, each member of the duo experienced their partner’s face as everchanging. Human features became animal traits, transmogrifying into grotesqueries. There were eyeless faces, and faces with too many eyes. The semblances of dead relatives materialized. Monstrosities abounded.

The bizarre perceptual phenomena that the pair witnessed were manifestations of the “strange face illusion,” first described by the psychologist Giovanni Caputo of the University of Urbino, Italy. Urbino’s original study, published in 2010, reported a new type of illusion, experienced by people looking at themselves in the mirror in low light conditions.

As we noted in an ensuing Scientific American Mindarticle,

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Caputo asked 50 subjects to gaze at their reflected faces in a mirror for a 10-minute session. After less than a minute, most observers began to perceive the “strange-face illusion.” The participants’ descriptions included huge deformations of their own faces; seeing the faces of alive or deceased parents; archetypal faces such as an old woman, child or the portrait of an ancestor; animal faces such as a cat, pig or lion; and even fantastical and monstrous beings. All 50 participants reported feelings of “otherness” when confronted with a face that seemed suddenly unfamiliar. Some felt powerful emotions.”

In his subsequent research, Caputo observed that the strange face phenomenon was not limited to one’s face reflected in the mirror, but it extended to other people’s faces, in situations where pairs of experimental participants gazed at each other for sustained periods of time in a dimly lit room.

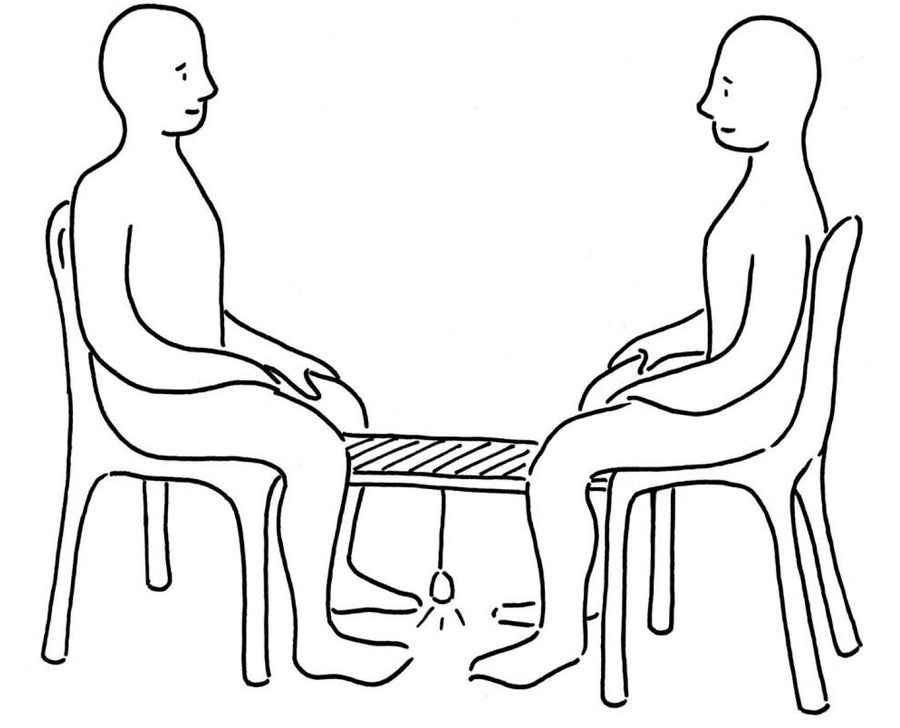

Experimental setup. Credit: Drawing by Alberto Conti

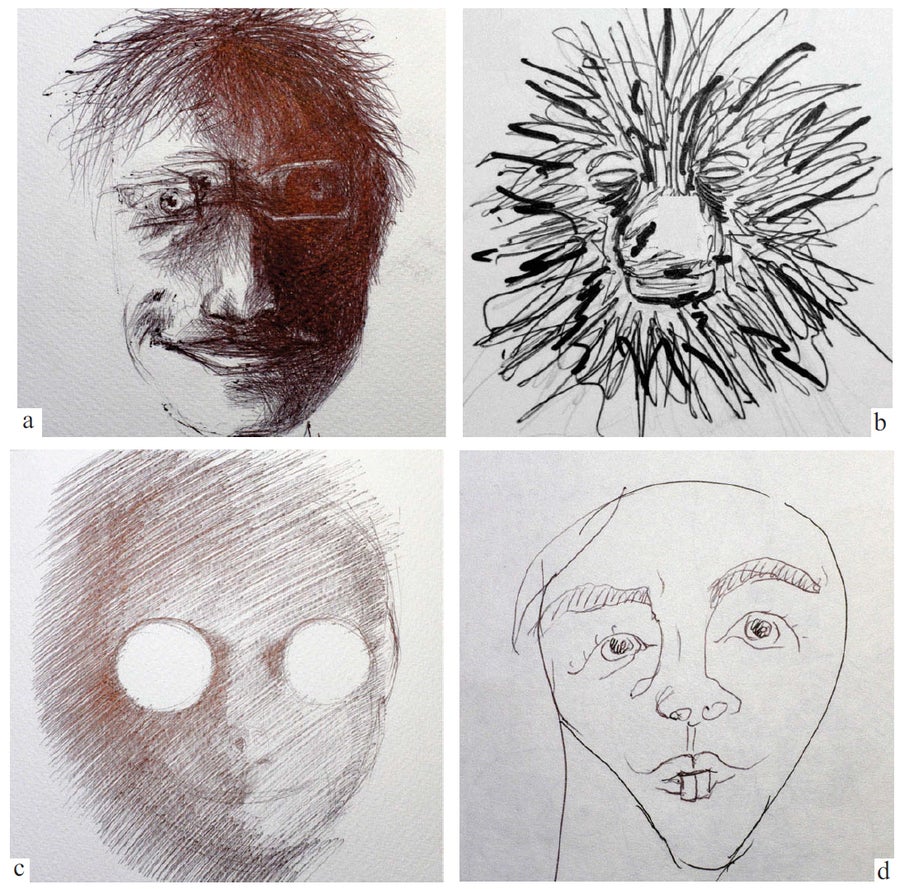

Most recently, in a study published last month in the Journal of Trauma and Dissociation, Caputo sought to test a large sample of participants, which comprised 90 healthy young adults. Notably, the participant population included 15 portrait artists, who were able to produce artistic depictions of their perceptual experiences at the end of the experiment. Four of such portraits are included below: a stranger with eyewear, a monkey-woman, an alien face, and a cartoonish human-rabbit face.

Four examples of strange-face illusions sketched by portrait artists: (a) Stranger with eyewear, (b) Monstrous monkey-woman, (c) Alien face, (d) Cartoon-like human-rabbit face. Credit: Giovanni Caputo

The mechanisms underlying the strange face illusion remain somewhat obscure. The perceptual vanishing of objects and scenes during prolonged gazing, known as Troxler fading, could be part of the explanation. When we stare at an unchanging face for a long time (our own face in the mirror, or the face of the person sitting in front of us), our visual neurons decrease their activity, making facial features fade and disappear (and then reappear when we blink or move our eyes). In the absence of such visual information, our brain is bound to “fill in” the gaps according to our neural wiring, expectations, and experiences—sometimes with fantastical results.

Future research may offer a more complete picture of why the strange face illusion arises. In the meantime, you may want to avoid candle-lit romantic dinners—or looking too long into the eyes of your beloved.