This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

According to the World Health Organization, almost one-third of women in the world have been victims of intimate or domestic partner violence. This public health problem has increased during the ongoing Covid-19 crisis due to the lockdown restrictions that have extended the time that family members spend in close proximity to one another. Though many countries have developed intervention programs for domestic batterers and their victims, recidivism rates have remained stubbornly elevated.

A new study, published in Frontiers in Psychology and led by Cristina González-Liencres and Maria V. Sanchez-Vives of the Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIPABS) and the University of Barcelona, Spain, highlights the potential of body ownership illusions to rehabilitate batterers—by putting them in their victims’ shoes.

Gonzalez-Liencres, Sanchez-Vives, and their colleagues set out to investigate the impact of an immersive scene of intimate partner violence, set in virtual reality, as experienced by either the victim or by an observer. The team recruited 32 non-offender male participants and assigned half of them to the victim scenario, and the other half to the observer scenario.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

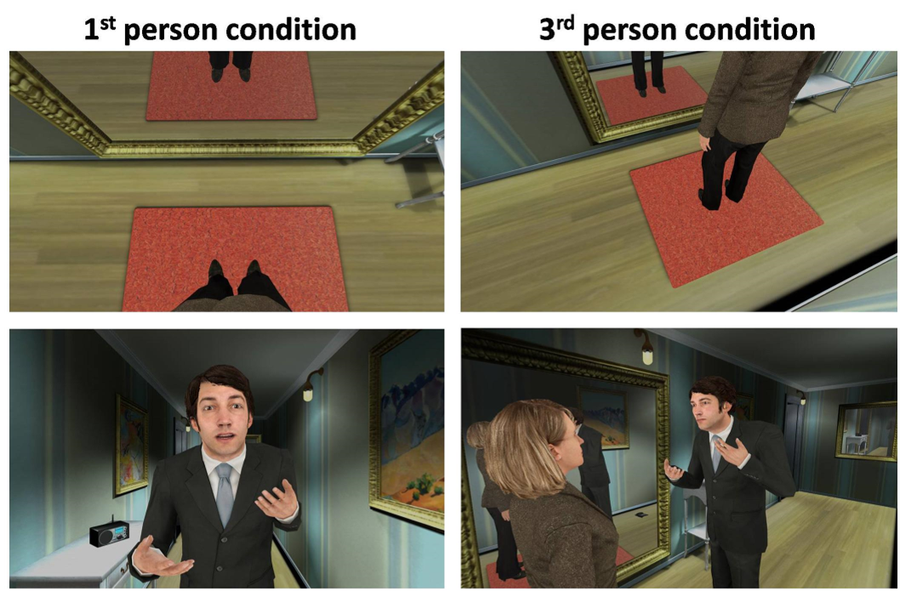

Head-mounted displays allowed immersing each participant in a hallway within a virtual house, where they witnessed abuse from a man towards a woman, either from the woman’s body (first-person perspective) or as a body-less observer (third-person perspective). First-person participants were able to see themselves in a mirror, with their reflection moving in synchrony with their own body. The experimenters recorded the electrocardiogram and galvanic skin responses of participants, in addition to their behavioral responses.

As the virtual scene developed, the man psychologically abused the woman, hitting a telephone at one point, and then approaching the victim and invading her personal space in a threatening manner, becoming more intimidating as time went on. In the first-person condition, the researchers could also make the virtual man say some predefined sentences, such as “Look at me!” when participants diverted their gaze, and “Shut up!” or “I told you to shut up!” when participants tried to speak. The abuse scene lasted three minutes in total.

From Gonzalez-Liencres et al (2020) Being the Victim of Intimate Partner Violence in Virtual Reality: First- Versus Third-Person Perspective. Front. Psychol. 11:820. Courtesy of Maria-V. Sanchez-Vives

The results showed compelling physiological reactions in both participant groups to the two main threatening events: when the virtual abuser threw the phone, and when he approached the woman shortly afterward. In addition, questionnaire responses indicated that people who took part in the scene from the first-person female perspective tended to consider the experience to be more real and threatening, with more intense feelings of fear, helplessness, alertness, and vulnerability. In contrast, those who participated from a third-person perspective experienced the virtual environment in a more detached way and with less threatened impressions, although they did still feel uncertainty, anxiety, and repulsion. Overall, stronger identification with the virtual woman was associated with a greater decrease in prejudice against women after the virtual reality experience. The researchers concluded that virtual scenes of abuse, experienced from the victim’s perspective, and to a lesser degree from an observer’s, could be useful in intervention programs intended to rehabilitate abusers.

As noted by the authors, a caveat of the study was that participants in the experiments had no history of violence, whereas there is evidence that batterers have a distinct psychological profile, which could limit the real-world application of the findings. Even so, the present results show promise with respect to the potential use of immersive virtual reality scenes in the rehabilitation programs of batterers, especially if experienced from the first-person perspective of the female victim.

The team is currently exploring how virtual reality may help prevent intimate partner violence both by preventing the occurrence of controlling and abusive behaviors and by rehabilitating perpetrators, including those in prisons. “Virtual reality can also help to support victims of gender violence, to decrease the blaming of victims, and to increase the awareness of this huge problem in society,” says Sanchez-Vives.