This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Even if you have never heard of biosimilar drugs, they stand to change medicine and the business of pharmaceuticals. Biosimilars are intended to do the job of certain innovative biologic drugs—complex medications, manufactured within living systems such as plant or animal cells, which target a range of diseases, from cancers to autoimmune disorders.

Biosimilars are sometimes described as the generic versions of biologics, which dominate any list of the top-selling drugs in America by revenue. In 2015, the last year for which complete figures are available, seven of the top 10 pharmaceuticals were biologics. Humira, Rituxan, Avastin, Herceptin and others each bring their manufacturers at least $5 billion in revenue per year. By 2020 the global sales of biologics are expected to exceed $390 billion.

Biologics have made many new, groundbreaking treatments possible. They are also very expensive, which is why people in medicine and policymaking have counted on what they sometimes call a “biosimilar revolution” to push prices down, much as generics have frequently replaced high-priced brand-name drugs in the past. Some have predicted cost savings from biosimilars in the U.S. and Europe to be as high as $110 billion by 2020.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

But, based on our own research and analysis, we urge caution. Because biosimilars are not simply generic replacements for brand-name biologics, we believe their effect on the cost of treatment generally will be much more modest than that of conventional generic drugs. This will be true in the short term and perhaps over the long term as well.

What Makes Biosimilars Different From Generic Drugs?

To understand why the economic effects of biosimilars are likely to be muted, it is important to highlight several key differences between biologic and traditional, chemically-derived drugs.

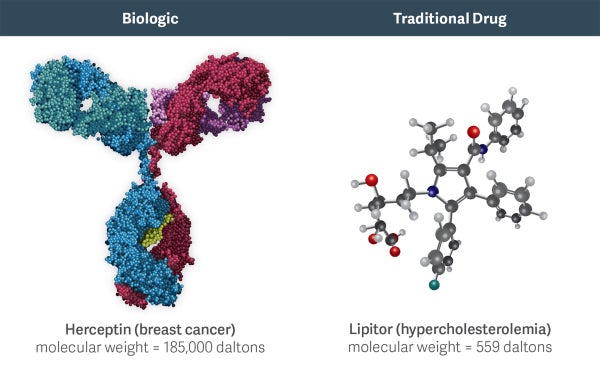

Biologics are much larger and more complex molecules than chemical drugs. For example, Herceptin (a biologic used to treat breast cancer) is 300 times larger than the active molecule in Lipitor (the popular chemical drug for cholesterol). In addition to size, differences in other structural features, such as protein folding, can further impact the effects of a biologic drug.

Consequently, biosimilars tend to be much more complex to manufacture and have far more variability than chemically-developed generic pharmaceuticals. As the word implies, a biosimilar is unlikely to be an identical molecular copy of the original, just very much like it.

Recognizing this complexity, the FDA currently requires costly and lengthy Phase III trials to approve a biosimilar, something they do not demand for generics drugs. Furthermore, while generics are frequently approved as “interchangeable” with a brand-name medication, draft FDA guidance indicates that it may require additional clinical studies (beyond the Phase III trials) to apply such a rating to a biosimilar.

In contrast to the robust generic competition that usually exists following the patent expiration of a brand name drug, these factors are likely to limit entry to a small number of biosimilars for any given branded biologic.

A key driver of generic drug penetration is the ability of pharmacists to automatically substitute an interchangeable generic drug for the brand. This “pharmacy substitution” policy is unlikely to be effective for most biosimilars. Even if the FDA adopts procedures for approving a biosimilar as interchangeable with the originator biologic, many biologics are administered by physicians rather than filled at pharmacies, minimizing the impact of pharmacy substitution.

Moreover, biosimilar manufacturers are likely to pursue more modest price discounts than generics and instead invest substantially in sales and marketing efforts to encourage their adoption in the absence of automatic substitution. As a result, penetration rates for biosimilars may be much more modest than for generics, and the price discounts may be substantially less. Indeed, biosimilar competition may share more features with traditional brand-vs.-brand drug competition than with brand-vs.-generic competition.

What has the Experience with Biosimilars Been So Far?

The FDA’s Biosimilar Product Development Program currently includes more than 50 biosimilars in the pipeline meant to be similar in use to more than 15 different biologics. To date, four biosimilars have been approved:

Zarxio (brand reference product Neupogen, a bone marrow stimulant) in March 2015

Inflectra (brand reference product Remicade, an immunosuppressant) in April 2016

Erelzi (brand reference product Enbrel, used against autoimmune diseases) in August 2016

Amjevita (brand reference product Humira, an immunosuppressant) in September 2016

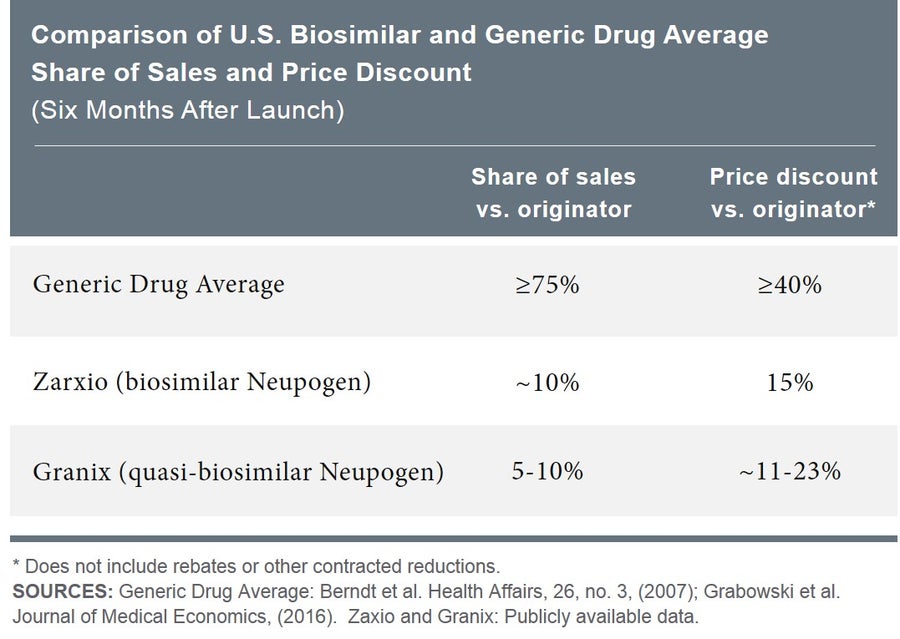

Empirical evidence shows that the impact of typical generic entry is rapid. Within six months of a generic’s appearance on the market, branded small-molecule drugs lose, on average, more than 75 percent of their sales, and generic price discounts relative to the brand price exceed 40 percent on average. In contrast, the branded biologic Neupogen lost only about 10 percent of its market share when the biosimilar Zarxio became available, and Zarxio’s price discount was only 15 percent. This is comparable to the experience following the earlier entrance of Granix, a quasi-biosimilar.

Biotechnology is an evolving discipline. Scientists will doubtless improve their understanding of how biologics and biosimilars work, as well as how their clinical profile (e.g. in terms of efficacy and safety/tolerability, convenience, etc.) can be improved. As this understanding evolves, so may the ability to develop biosimilars that are increasingly similar to the brand in their clinical profiles. But if biosimilars indeed represent a revolution, it is just beginning.

-

Richard Mortimer and Alan White are Managing Principals and Christian Frois is a Vice President, all with Analysis Group, Inc. They have considerable experience undertaking empirical research on the economics of biosimilars. They have applied that expertise in expert witness assignments in antitrust and intellectual property legal disputes, and have provided strategic consulting to biopharmaceutical manufacturers facing biosimilar competition.