This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Alex Rogan masters a video game called “Starfighter” where he defends "the Frontier" from "Xur and the Ko-Dan Armada" in a space battle. Soon after he becomes the world’s highest scoring player, the teenager meets an alien who informs him that the battle is real! The video game was a test and a recruiting tool, meant to find those with “the gift” to pilot a real Starfighter spacecraft. Now it will be up to Alex to save the Galaxy.

That’s the plot of the 1984 space opera The Last Starfighter. And I think it’s a useful model for citizen science projects, where untrained laypeople are invited to take part in performing professional scientific research.

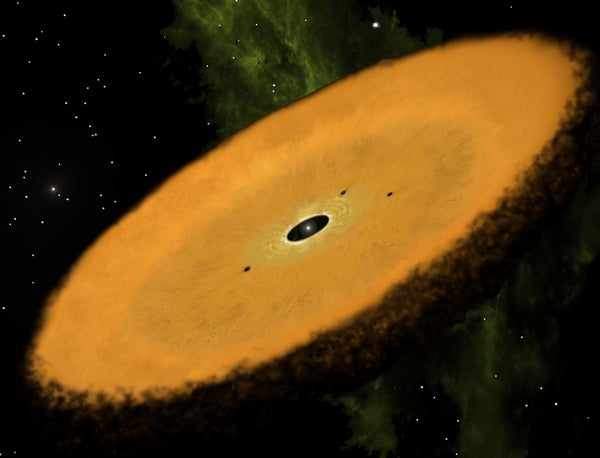

Since January 2014, I’ve had the honor of leading a citizen science project called Disk Detective, which is funded by NASA and part of the Zooniverse citizen science community. The project aims to find new planetary systems using data from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and other surveys; we recognize these systems by the infrared light radiated from circumstellar disks. At DiskDetective.org, users view ten-second videos of each astronomical source, and help us rule out false positives by clicking buttons to describe what they see.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Our top users are not teenagers in trailer parks like Alex from The Last Starfighter. But they certainly do have “the gift,” i.e., a passion for science. While roughly 30,000 people have participated in the project at some level, so far, more than half of the online classification work at DiskDetective.org has been performed by a group of roughly 30 dedicated citizen scientists, working round the clock, chasing the next big discovery.

Even more impressive to me than the roughly 1,000,000 classifications performed by this group at the Disk Detective website are the thousands of additional hours this team has spent working on the project offline, so to speak. This “advanced user group” organized themselves, starting their own Google group and Facebook group to communicate with one another. They have helped the project by:

Building and maintaining spreadsheets of thousands of the best targets for follow-up on six telescopes around the world.

Researching thousands of disk candidates in the professional astronomical literature to find out who may have observed it before and to determine the most likely spectral type of the star.

Downloading professional astronomical software, and sorting through thousands of follow-up images to check our disk candidates for additional background objects.

Driving 12 hours across South America to the CASLEO observatory help with an observing run.

Translating the DiskDetective.org website into Spanish, German, French, Italian, Portuguese, Russian, Polish, Bahasa, Hungarian, Mandarin (Simplified and Traditional characters) and even tweeting updates in Spanish, so people around the world can participate more easily.

Attending professional astronomical conferences and proofreading our professional publications.

Double-checking subsets of our rejected sources to look for certain kinds of rare astronomical objects

Giving talks and writing Wikipedia articles about our results, and creating original artwork that we have used in our press releases;

Introducing us to professional colleagues who could take follow-up observations of our disks at new telescopes could follow up our favorite disks at new telescopes--and did!

These contributions have taken us far beyond the original scope of the project. Moreover, our advanced users have also helped teach one another about the science of disks and stellar spectroscopy, creating elaborate online guides for one another to read, and coaching one another one-on-one. That task hasn’t always been easy given that English is a second language for many of our users.

Sometimes my colleagues will ask me: could Disk Detective possibly have been done by computer? Could a clever machine-learning algorithm replace the hard work of the citizen scientists? Indeed, a series of innovative computer analyses by several teams of professional scientist have uncovered many of the brightest disks in the WISE archive in the six years since the data became available. So the competition between computer-aided professionals and teams of citizen-scientists is keen.

But Disk Detective has already made several discoveries that the teams of professionals did not, despite having access tothe data several years before our project launched. We published our first two papers this month. One described what appears to be the first debris disk ever found around a star with a white dwarf companion. The other announced a new disk candidate around a cool star that appears to be a member of the Carina association of young stars: the oldest “M dwarf” disk in an association. Moreover we at Disk Detective have found many mistakes in the published computer analyses; false positives where a human eye was truly needed to make the right call.

But I think our best discoveries of all have been our “Last Starfighters,” the passionate citizen scientists in the Disk Detective advanced user group: a retired doctor, a retired biologist, a computer scientist, students of law and geodesy, a postal worker, grandparents, teachers, a single mom—each with unique talents and perspectives. Even after Disk Detective has found its last disk, they will probably continue to serve humanity through their science. Some even have applied for jobs in astronomy inspired by their work on Disk Detective.

So the next time I launch a citizen science project (and that will be soon) I will certainly ask myself: could the basic online classification task be done better by computer? But I will also remember that a citizen science project run right is a talent search. Right from the start, I will build in new ways to inspire and connect with the project’s most active users. And I will do my best to stay in touch with the international community of citizen science superstars that is emerging, and find new ways to work with them throughout my own career. There is a lot of scientific talent out there, just waiting for a chance to save the Galaxy.