This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

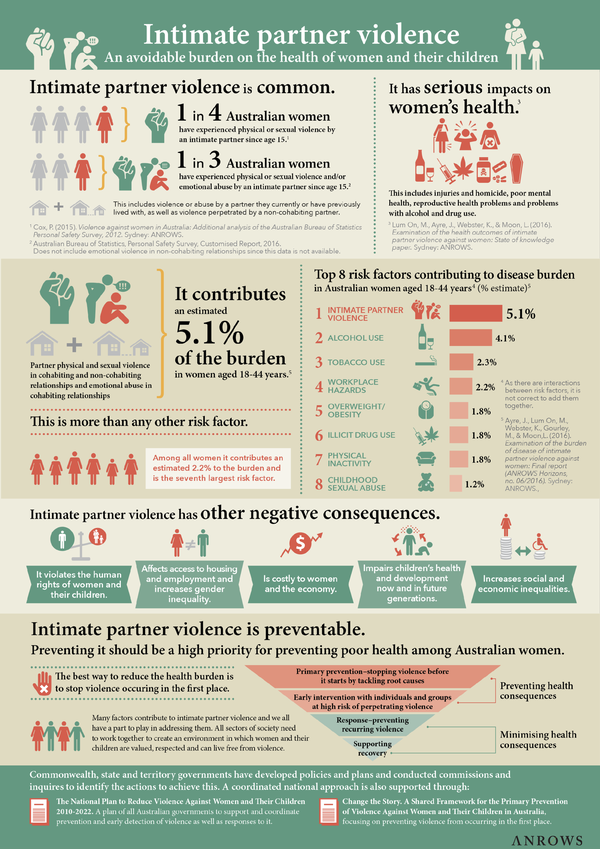

A new national study published by Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) shows that intimate partner violence poses one of the highest health risks for all Australian women, and is the greatest contributor to health risk amongst women aged 18 to 44. The contribution of intimate partner violence to the “burden of disease” is greater for women of child-bearing age than alcohol use, tobacco use, cholesterol, obesity and other diseases. The pattern found in Australia is, unfortunately, not uncommon in other high income nations, as identified by the World Health Organization. The study was commissioned by ANROWS and conducted by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) to contribute to evidence for implementation of Australia’s National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (2010-2022). The National Plan is an initiative of the Council of Australian Government’s (COAG) and its goal is a significant and sustained reduction in rates of violence against women and their children by 2022.

The published study shows that one in three Australian women have experienced physical, sexual and/or emotional abuse by an intimate partner. The figure is one in six women when emotional abuse is excluded. Some groups, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (Indigenous Australian) women experience higher rates of intimate partner violence; disability and socio-economic marginalisation also increase risks of intimate partner violence victimisation. Women who are pregnant or who have children in their care are also especially vulnerable to intimate partner violence.

Calculating the Burden of Disease

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The burden of disease is accepted globally as a rigorous, best-practice methodology for measuring the health impact of injuries, illnesses and conditions (collectively referred to as “diseases” in this methodology), and making comparisons between them. The burden of disease measures loss of health at a population level for a particular year, in this case 2011. The methodology uses representative national datasets for prevalence rates of diseases in the population. The Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Personal Safety Survey (2012) provided the data source on prevalence of intimate partner violence among women in the Australian population. The study also uses the ABS’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey and General Social Survey to calculate prevalence rates of diseases. Data on emotional abuse in cohabiting relationships has been included in the calculation for the total population of Australian women, but these data are not available at the national level for racial minorities, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women.

The health loss calculation takes into account premature death and the severity and impact of non-fatal diseases to produce a “Disability-Adjusted Life Year” (DALY). The DALY is a single measure of years lost due to homicide or suicide and poor health associated with disability, chronic illness, mental health conditions, substance abuse, maternal and reproductive health disorders, and sexually transmitted infections. The results of the DALY are expressed as percentages, or “rates of burden”.

The AIHW examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence is drawn from its broader burden of disease study which calculated the burden of about 200 diseases. The examination of the burden of disease of intimate partner violence involved a meta-analysis of 43 studies linking intimate partner violence to health issues (more than 7,000 such studies were considered for inclusion but most were deemed insufficiently rigorous for the meta-analysis). Data from these studies were extracted to calculate whether there was a strong or weak association between intimate partner violence and the seven most prominent diseases emerging from the analysis: depression, anxiety, suicide and self-harm, homicide and injuries, alcohol-use disorder, preterm and low birth weight complications and early pregnancy loss.

Health Impacts

Research shows that intimate partner violence makes a strong impact on health outcomes. This is because this violence is perpetrated over a period of time and the effects are cumulative. Some of the health consequences are immediate, such as physical injuries, while others may develop over time as a result of violence, and they can be co-occurring years after the abuse ends, such as alcohol dependency and poor mental health. The effects of intimate partner violence also have a profound compounding effect on health, by deepening existing inequalities, as is the case with Indigenous Australian women. Flow-on health risks extend to children who are exposed to violence.

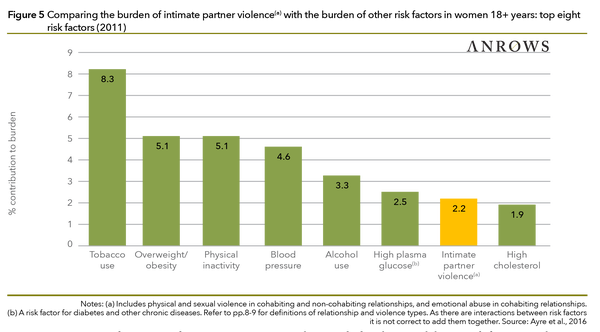

In the ANROWS-AIHW study, intimate partner violence contributes 2.2 percent to the burden of disease of all women. To put this in context, the highest burden is 8.3 percent due to tobacco use and the second and third highest health burden is 5.1 percent each for being overweight or obese and physical inactivity. High cholesterol contributes less to the total burden of disease at 1.9 percent for all Australian women. As the figure below shows, despite the proportion of the burden seeming to be a small percentage, intimate partner violence actually ranks seventh amongst all health risk factors for women aged over 18 years.

Source: A Preventable Burden ANROWS

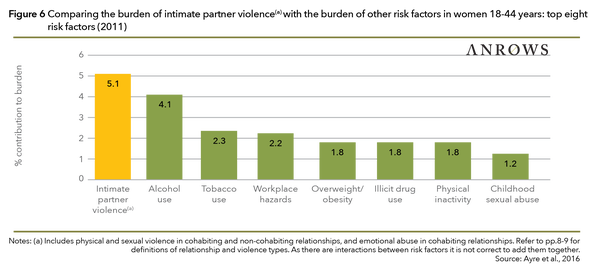

When we drill into the data for women of child-bearing age, intimate partner violence is the highest health risk factor. Intimate partner violence contributes to 5 percent of the disease burden of women aged 18 to 44 years, compared to 4 percent for alcohol use and over 2 percent for tobacco use. This ranking remains whether or not intimate partner violence includes emotional abuse alongside physical and sexual violence.

Source: A Preventable Burden ANROWS

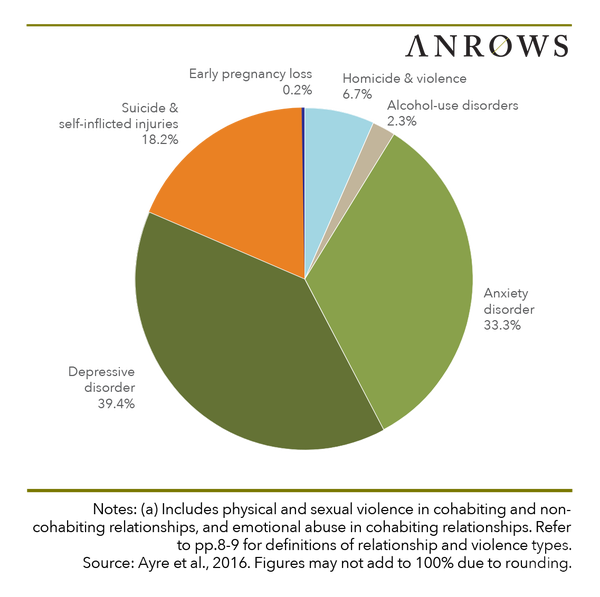

The biggest proportion of the health burden of intimate partner violence is due to its impact on depressive disorders (39% of intimate partner violence burden for all women) and anxiety disorders (33 percent), followed by suicide and self-inflicted injuries (21 percent) and homicide & violence (13 percent).

Source: A Preventable Burden ANROWS

Indigenous Australian Women

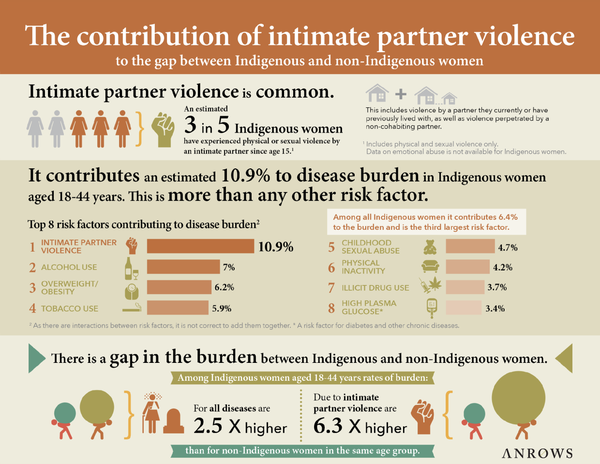

While there are no national data for emotional abuse of Indigenous women, the available data on physical and sexual violence show that intimate partner violence is more prevalent for Indigenous women (noting that perpetrators may be Indigenous or non-Indigenous). Amongst all adult age groups, Indigenous women experience a burden of disease of 6.4 percent due to physical and sexual violence, compared to 4.6 percent for all Australian women (for both cohabiting and non-cohabiting relationships). This makes intimate partner violence the third highest of all health risks for Indigenous women (compared to the 7th highest for all Australian women).

Amongst Indigenous women aged 18 to 44, the burden of physical and sexual violence is 10.9 percent compared to 7.3 percent for all Australian women. This is the highest disease burden for Indigenous women in this age group, even greater than alcohol use (7 percent), being overweight or obese (6.2 percent) and tobacco (5.9 percent). Looking at the impact of this violence on other health issues, the burden of disease of intimate partner violence accounts for half of suicide and self-inflicted injuries as well as half of early pregnancy loss; and over a third each for anxiety and depressive disorders.

Overall, the difference of the disease burden of intimate partner violence is 6.3% higher than for non-Indigenous women at the national level; for women of child-bearing age, the difference is 15.3%.

Source: A Preventable Burden ANROWS

The Role of the Health Sector

The burden of disease study shows that intimate partner violence is the greatest risk to health for Australian women aged 18 to 44. Moreover, there is a gap in the burden of disease between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian women; the burden of disease attributed to intimate partner violence is more than six times greater for Indigenous women than non-Indigenous women. This finding highlights that significantly reducing and ultimately ending intimate partner violence against Indigenous women, is necessary to achieve another COAG goal—closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in a number of key areas including health and life expectancy.

While the causes of intimate partner violence are complex, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other research bodies have well-established the empirical basis for its prevention. The United Nations and others, including Australia’s Our Watch, ANROWS and VicHealth have established that gender inequality is the most significant driver of intimate partner violence, although a wide range of factors are contributors to it. They include beliefs, family relationships, norms, social structures and practices within communities, workplaces, schools and sporting clubs, institutions such as the media and the criminal justice system and for Indigenous women, the intersections of gender and racialised inequality associated with colonisation.

The burden of disease study by ANROWS-AIHW shows that reducing and ultimately eliminating intimate partner violence will have a significant positive impact in preventing and reducing mental illness, suicide and self-harm, homicide, and alcohol misuse as well as improving maternal and reproductive health. It indirectly shines a light on the role of health practitioners in early detection of intimate partner abuse, sensitive inquiry and appropriate referral to reduce the harmful effects of continued exposure to this significant health risk. Health practitioners and others also have a critical role in the long-term counselling and mental health support for women recovering from intimate partner violence.

The impacts of intimate partner violence are broad and deep—achieving the goal of the National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010-2022, and the goal of the closing the gap on Indigenous disadvantage, requires concerted effort from all sectors and there can no longer be any doubt about the role of health sector in responding to intimate partner violence.

Source: A Preventable Burden ANROWS