This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Creativity may not be a term that the average person would associate with DNA research or space exploration, but the youth science competition Genes in Spaceis showing students and teachers that the concepts actually go hand-in-hand. The competition introduces students to cutting-edge technology, asks them to propose real-world questions about the effects of space travel on living organisms, teams students up with science experts, and then performs the winning experiment on the International Space Station.

The competition, which named 16-year-old Anna-Sophia Boguraev as its first winner last week, is the collaborative effort of Boeing, Math for America, miniPCR, and the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space. Though very different in their approaches to science and education, each of the collaborators came together for the vision of a chance for young people to apply their most creative minds in a very real research setting.

Genes in Space competitors are given a highly open-ended task (propose an original research question) in a somewhat open-ended field (any way in which living organisms might be affected by time in space) with a decidedly specific set of tools (as can be studied using a miniPCR in the International Space Station). This combination of open creative inquiry and limited resources serves as an excellent analog to the tasks that career researchers face every day. And according to Math for America President John Ewing, the openness of the proposal aspect of the competition was quite intentional.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Too many science classes nowadays have to do with memorizing facts,” Ewing said. “Even some of the science competitions are just competing to see who has memorized the most facts. It just isn’t active in the way that real science is.”

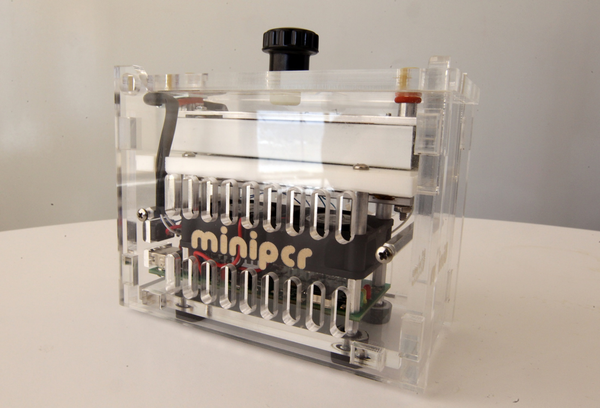

Genes in Space brings kids not only into a more realistic science process, but it asks them to use technology and processes that are still used by cutting-edge researchers today. To look at the miniPCR it may not seem particularly powerful, but it actually represents a technology that has made it from winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry to working in a K-12 classroom in under 25 years.

The processes of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are able to rapidly detect or analyze DNA or amplify a single copy of a piece of DNA into millions of copies for analysis. It is one of the reasons that your favorite television detectives might be able to pull that tiny fragment of DNA into something meaningful.

miniPCR - which will be used in the ISS to conduct the winning experiment - takes the power of traditional PCR processes and condenses them into a 2-inch by 5-inch package that hooks directly to a smart phone and weighs less than a pound (Photo Courtesy of Genes in Space)

Taking that technology into the International Space Station with a miniPCR opens a new set of doors for the way we study the subtle effects that everything from microgravity to cosmic radiation might have on living organisms – and the student competitors of Genes in Space are getting the chance to ask some of these questions first.

That is where the creativity part comes in. The Genes in Space website has a number of suggested ideas to get the kids started – ranging from DNA chemistry to the detection of life – but it also contains the important phrase, “or come up with an entirely new idea!”

Ewing highlighted how the most innovative breakthroughs in science have come from creative minds; from the people who pursue the questions or approaches that no one else would have thought of. “But in school when a kid is identified as a ‘creative’ personality, science is not the pursuit that they are typically encouraged to follow,” said Ewing. “The most creative minds might be led to believe that the only place to be creative is the arts, and that means that science is losing the interest of many vital young creative minds.”

Once the students finished their independent proposals, those selected as finalists were matched up with expert mentors to help them hone their question from the idea phase into something that could actually be tested on the ISS. The collaborations took place in person or online, depending on the location of the finalists, and were a delicate balance between providing meaningful feedback and letting the finalists find their own way. But overall, the mentors were delighted by the work and ambition of their young finalists.

Genes in Space 2015 Winner Anna-Sophia with astronaut Suni Willams (Photo Courtesy of Genes in Space)

Deniz Atabay of MIT worked with finalist Alyssa Huff. "When we were interacting regarding her project’s experimental details, the most surprising aspect for me was her deep understanding of the concept she was proposing,” said Atabay. “It’s important to note that her idea for an experiment is one that could be expanded and transformed into a larger scale project that might one day allow us to devise novel strategies to detect new life forms and even further advance the current research on ISS."

Holly Christensen, also of MIT, served as the mentor for the eventual winner of the competition, Anna-Sophia Boguraev. The two communicated extensively via email and Skype over the 6-week finals period, and Christensen was “very impressed with the sophistication of Anna-Sophia’s proposed experiment and the biological relevance of her research question.”

Finalists gave presentations for their proposals before a panel of judges, including Ezequiel Alvarez Saavedra, co-founder of miniPCR; Elinor Karlsson, assistant professor, University of Massachusetts Medical School; Uzma Shah, MƒA Master Teacher; Gary Ruvkun, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School; Breton Hornblower, lead of DNA amplification technologies at New England Biolabs; and Philip Schein, member of the board of CASIS.

Anna-Sophia and the whole Genes in Space team are excited to see the winning experiment conducted in the International Space Station.

At the end of our conversation I asked Ewing about the other participants, the ones whose experiments will not get to go to space, and what he thought they might take away from the experience.

“At least they have had the chance to think about something truly interesting,” Ewing said. “They have been encouraged to think about something crazy and at the cutting-edge of science, and hopefully they will feel like this kind of cognitive creativity is something worth engaging in again and again.”

Sources:

Center for the Advancement of Science in Space