This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

It’s doubtful but maybe, just maybe, if Gary Johnson ever tried muhammara, he might have avoided his epic flub, “What’s Aleppo?”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Had he tasted it, it may have piqued his curiosity to learn more about the Syrian spread and why one of its quintessential components--Aleppo peppers--are increasingly hard to get.

Ranking at about 10,000 on the Scoville scale, the Aleppo pepper has a medium level of heat, a distinctive fruitiness with earthy flavor and hints of cumin. Renowned ethnobiologist and noted chile pepper enthusiast Gary Nabhan has written about their history and challenges. Also known as a halaby chile, the Aleppo pepper is named for the city in which it originated. It was grown by Christian and Muslim Arab farmers, possibly nurtured by Sephardic Jewish spice merchants, and traded along the Silk Road.

For centuries, the pepper has been used to season kebabs, stews, and sauces. The moderately hot pepper has recently been met with challenges from rising heat--specifically, the planet’s increasing temperatures. In 2010, Nabhan wrote about how climate change was impacting pepper production. According to Nabhan:

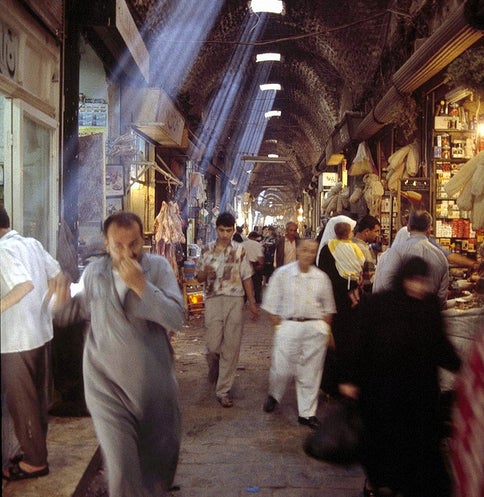

The Aleppo pepper has been sold in markets throughout Syria, including Aleppo’s famed Al-Madina Souk which has been damaged during the war. Credit: FULVIO SPADA Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The same climate-driven pressures are affecting the survival of the Halaby pepper and its traditional farmers near Aleppo, Syria. In the past three years, 160 Syrian farming villages have been abandoned near Aleppo as crop failures have forced over 200,000 rural Syrians to leave for the cities. This news is distressing enough, but when put into a long-term perspective, its implications are staggering: many of these villages have been continuously farmed for 8000 years. As one expert puts it, this may be the worst long-term drought and most severe set of crop failures since agricultural civilizations began in the Fertile Crescent many millennia ago.

The thousands of tourists and residents who purchase Urfa and Maras chiles in Istanbul’s Spice Bazaar may not yet realize it, but their access to these world class spices is being disrupted by climate change. Since 2007, rains in some forty Turkish provinces, northern Syria and eastern Iraq have been 30 percent to 40 percent of their normal levels. The drought in southeastern Anatolia has reduced harvests by 80 percent. In Syria, 60 percent of the agricultural lands have been affected by these droughts.

In 2011, civil war (which has been linked to climate change) began in Syria, making the pepper increasingly more scarce. Given the inherent devastation of war, considering the impact it has had on Aleppo peppers might seem trivial to some. Others see it as important to the preservation of one of the world’s oldest cultures. Writing about efforts to save the pepper, Cathy Barrow notes on National Geographic’s The Plate, tradition and cuisine are a source of pride for many Syrians. She says,“With hundreds of thousands dead and livelihoods destroyed by the conflict, the loss of a spice might not seem like a big deal, but it’s not just a flavor, it’s history."

Other species of plants considered integral to Syrian agriculture have been put at risk by civil war. An impressive effort has been made to retrieve ancient varieties of wheat and durum. Their origins can be traced back to the Fertile Crescent’s beginning. Scientists have gone to extensive lengths to safely transport them to genebanks in other countries since their seeds contain valuable genetic resources.

Fans of the Aleppo pepper are doing their part to save it, as well. It is being swapped and sold worldwide and Syrians are safely storing their seeds for when they will be able to start anew.

_______________________________________________

Muhammara is a mildly spicy pepper and walnut spread that originated in Aleppo. Named for its rich hue, muhammara comes from the Arabic word for reddened. It can be served as a meze, or with fish, chicken, or other meats.

Here’s cookbook author and chef Anissa Helou’s version of the tasty dip.

Credit: Layla Eplett

Muhammarah

6 red bell peppers

100 g (1 cup) breadcrumbs

½ tablespoon sugar

1 tbsp cumin

1 tablespoon Aleppo pepper flakes

juice of ½ lemon

1 ½-2 tablespoons pomegranate syrup

3 tablespoons olive oil

½ tablespoon tahini

100 g walnuts, coarsely ground (about ¾ cup), plus extra for garnish

sea salt

Spread the peppers on a baking sheet and place under a hot grill quite close to the heat. Grill for 15-20 minutes on each side until the skin is quite charred and the flesh very soft. Place in a bowl to collect the juices, which you may need later. Then, remove one pepper at a time onto your work surface. Take out the stalk and seeds and peel. Place in a food processor. Trim and peel the remaining peppers and process until chopped finely but not completely pulverised. You want the purée to retain a little texture.

Transfer to a mixing bowl.

Add the rest of the ingredients and salt to taste. Mix well. Add a little of the pepper juice if the dip is too thick. It is supposed to be textured and a little thick but not dense. Taste and adjust the seasoning if necessary. Serve drizzled with olive oil and garnished with a few chopped walnuts.