This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

This is a guest post by Chadene Tremaglio. Chadene received her PhD in Microbiology from Boston University in 2014, and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Find her on twitter.

I recently took my daughter to her sixth-month pediatric appointment. The visit was pretty routine; the doctor measured her height, weight and head circumference, and assessed her physical and mental development, finally declaring her “healthy and on-track”. All was going as expected, and then the subject of feeding came up and everything I thought I knew about introducing solid foods was thrown for a loop.

Our pediatrician informed us that the latest guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) were to introduce peanut-based foods to infants as young as four months old in an effort to prevent peanut allergies! To say I was surprised would be an understatement, and our pediatrician even confessed to a certain amount of discomfort, as it went against more than a decade of pediatric guidance about peanut allergy prevention. Just three years ago, we were told it was okay to start feeding my son (my first child) solids between four and six months, but to avoid things that are commonly allergenic such as strawberries, tropical fruits, eggs, and peanuts, until he was closer to a year old. And as of the year 2000, clinical practice guidelines in the US still recommended pregnant women and nursing mothers also avoid allergenic foods in their diets.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Food allergies are foremost on the minds of many parents, and peanut allergies in particular instill an intense fear. They typically develop very early in life, are rarely outgrown, and are the leading cause of food-related deaths. The grave seriousness of peanut reactions has led many schools to go “nut-free”, prohibiting peanut butter and all peanut products in lunch boxes, in a vigilant effort to save lives.

Nearly every parent has encountered horrifying anecdotes of peanut-induced anaphylaxis, and I doubt I am the only mother who has scrutinized my child’s face during lunch time, worrying disproportionately about a strange spot or two near his mouth, and asking my son if his mouth feels “tingly” (side note: a 3 year old, perceptive of the paranoid look on your face, will always answer, “yes”, to this question so ask at your own discretion). However, our society’s collective allergy anxiety coupled with a clinical strategy of avoidance has been largely ineffective; in the past ten years the prevalence of peanut allergies in children in the Western world has doubled, and has nearly tripled in the US alone. And no study has been able to show that elimination of allergens in the diet can prevent the development of food allergies. Which is why in 2008, the AAP stopped recommending delayed introduction of common allergenic foods.

That same year, the curious observation was made that Jewish children in the UK had a 10 times-greater risk of developing peanut allergies than their Israeli counterparts. One possible explanation for this difference was that the Israeli children were being exposed to peanut products on average at approximately 7 months of age (thanks to the popular “Bamba” snack food), whereas the UK children were typically not consuming peanuts until after their first birthday. This led to the hypothesis that early exposure to peanut products may actually be the key to preventing peanut allergy, in direct contrast to the earlier theories that avoidance was protective. To test this hypothesis, a collaborative network of clinical researchers called the Immune Tolerance Network (ITN) designed and conducted the LEAP study (Learning Early About Peanut allergy) at Kings College London. They enrolled 600 children between the ages of 4 and 11 months, all of whom were at high-risk for developing peanut allergies (they all had severe eczema and/ or egg allergy). The children were randomly assigned to two groups; one group was fed peanut-based foods at least three times per week (the “consumption group”), while the other group was told to avoid peanut products (the “avoidance group”). Researchers, led by Dr. Gideon Lack, followed the children up to age 5, looking for signs of peanut allergy by skin-prick tests and checking serum levels of peanut-specific antibodies.

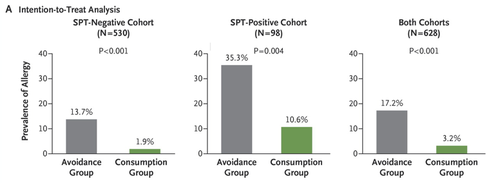

The results were astonishing: in the consumption group, only 3% of children went on to develop peanut allergies, compared to 17% in the avoidance group. This corresponded to an 81% reduction in peanut allergies in high-risk children who consumed peanuts early and often. These results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) in February 2015, and changes to the clinical practice guidelines were implemented rapidly in response to this study. Nevertheless, it remained to be shown whether or not the protective effect of early exposure to peanuts would be lasting and durable after a break from eating peanut products.

Green bars are the kids that got the early peanut treatment. "SPT" is skin prick test. Source: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1414850

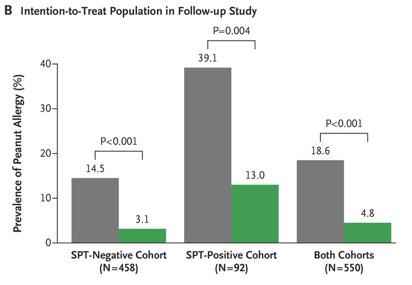

This question was investigated in a 12-month extension of the original study, called the Persistence of Oral Tolerance to Peanut (LEAP-On) study, and published in NEJM in March of this year. The participants in both groups from the LEAP study were instructed to avoid peanuts for one year, and clinical assessments were repeated at 6 years old. The results showed that in the group of children who were fed peanuts regularly for the first 5 years of life, there was no significant increase in the prevalence of peanut allergy after one year of avoidance, while peanut allergy was significantly more prevalent in the original peanut-avoidance group. The take-home message of these two studies is that exposure over long periods of time, rather than avoidance, may be an effective strategy to prevent the development of a life-threatening peanut allergy.

Source: http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1514209

Despite the great promise of these groundbreaking trials, it is important to note that researchers involved in the study recommend parents of children with eczema or egg allergy, or a family history of food allergy, meet with an allergist before feeding their children peanut products. And since the study was focused on prevention of peanut allergy and not the treatment of an existing allergy, children who have already a reaction to eating peanuts (including rashes, vomiting, diarrhea, wheezing, and more) should not be fed peanut-based products without first being seen by a physician. Additionally, this study only applies to the prevention of peanut allergy; whether or not this strategy will be effective for other allergenic foods has not yet been rigorously tested.

So, will I be introducing my daughter to peanut butter anytime soon? Perhaps. She is not considered high-risk for the development of food allergies, and this study did not assess the risk or benefit of the early introduction of peanuts to children with lesser or no peanut allergy risk factors. The study also does not define how much peanut-based food needs to be given, and does not determine the minimum amount of time that children need to be on the peanut regimen for the protective effect to be lasting. Still, I think I would feel comfortable offering her some peanut butter at home as soon as she seems able to handle the texture, while watching her closely for any sign of a reaction. At worst, it can’t hurt, and at best, it may ensure she is able to enjoy peanuts for years to come.