This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

During iftar, the evening meal in which Muslims break their fast during Ramadan, guests of Mehmed the Conqueror were given a pilaf with chickpeas. According to legend, one chickpea in the pilaf was made of pure gold. Like the British tradition of finding a silver sixpence in Christmas pudding, the guest that found the golden chickpea kept it as their dis kirasi, a special gift given during the holy month.

Although the Ottoman Empire embodied opulence and decadence, Batur Durmay, owner of Asitane restaurant in Istanbul, suspects this story might be slightly exaggerated since it was not traditional for sultans to dine with guests. The restaurant’s name reflects its food--Istanbul was once Constantinople, and at one time during the Ottoman empire, it was also known as Asitane. Since opening his restaurant, Batur has become somewhat of an authority on Ottoman Empire cuisine. The restaurant meticulously recreates dishes from the empire, using archival records and other sources from the palace.

In order to make the experience at Asitane authentic, Ottoman dictionaries were used to translate archival information from Topkapi, Dolmabahce, and Edirne Palaces. To create their iftar menu, they use palace kitchen ledgers, accounting books, diaries of guests and port tax authority reports to cross check the ingredients.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Records indicate planning for the month long feast and festivities would have begun up to a year in advance. The palaces had the equivalent of an executive chef who would draft the menu, create a budget, oversee the growing of ingredients, and also source some foods from companies. “Palaces had a very well established product supply chain,” explains Durmay. Their treasury accounts reveal that some items were ordered well beforehand, like pickled eggplant, lemon marmalade, and gum mastic that was imported from the island of Chios.

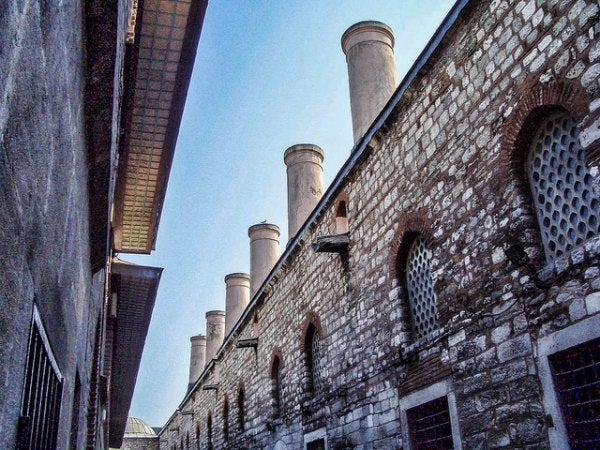

The Ottoman Empire spanned over six centuries so the number of iftar guests varied depending on its prosperity. While the exact number of attendants isn’t known, it can be estimated by the size of the kitchen staff. During Mehmed the Conqueror’s reign, there were between 250-260 people working in the kitchen; the period under Suleiman the Magnificent was much more affluent, and his staff of nearly 1,150 people would have made meals that were far more grandiose.

The tall kitchen chimneys of Topkapi palace, located in modern day Istanbul. Image by Enric Rubio Ros via Flickr.

The interior of a kitchen in Topkapi Palace. Image by erin via Flickr.

“Iftar menus are special but, of course, all palace menus are special also. The quality of the ingredients would be very high,” explains Durmay. Rare ingredients, like crystallized sugar, were used as well as musk, amber, saffron and other exotic spices from the three continents included in the empire. The vastness of the Ottoman Empire was reflected in its food. Exploring the cuisine at Topkapi Palace, Jason Goodwin writes:

The city lay at the confluence of many currents of trade, drawn across an empire that stretched from the Balkans to Egypt, and from the borders of Georgia to the Adriatic. Egypt was the Ottoman’s granary. Anatolia was their fruit bowl. The mountain pastures of Europe and Asia provided them with sweet mutton and cheese. Every region had its specialty, like the delicate and delicious trout of Lake Ohrid, on the border between Macedonia and Albania, which were carried overland, live, to Topkapi Palace for the sultan’s feasts. The best of everything arrived there in its season—watermelon and green onions from Bursa, figs from the Aegean coast, fruit from the Black Sea. Vegetables came from market gardens snuggled up beneath the ancient Byzantine walls, within living memory, and different districts of the city became famous for certain products, like the clotted cream of Eyüp, or the flaky pastries of Karaköy. Meanwhile, the finest garlic came from İzmit, lemons from Mersin, cheeses in skins from the mountains of Moldavia. This was an imperial palace in a city of imperial appetite, and not for nothing has the palace cookery of Istanbul been defined along with the Chinese and the French as one of the three great food cultures of the world.

Since Ramadan occurs eleven days earlier each year, the foods served also changed according to the season--stews and heavier dishes were eaten in winter and lighter foods were consumed during summer. Iftar foods varied not just according to weather but also depending on status. More basic provisions were given to the poor--the palace would send out trays containing plain soups with cracked wheat, as well as a pilaf, possibly a meat, and a simple compote for dessert.

In more extravagant times, there are records of iftars for more influential guests that would contain four dinners served sequentially on the same evening, “like a tasting menu by Paul Bocuse,” says Durmay.

For guests during more prosperous periods, eight to ten guests would traditionally break their fast seated around a sofra, a low round table with a copper tray, covered with an assortment of foods like the ones served at Asitane's iftar--some of their traditional components include dates, olives, sun dried apricots, lor mahlutu (a cheese blend from 1898), oven baked bourak with purslane and cottage cheese from 1844, and visneli yalancı sarma (stuffed vine leaves with sour cherries from 1844).

Image courtesy of Asitane.

The following course would be a soup, served in a communal ceramic bowl that individuals would consume using their own spoons.

Then, bowls of pilaf would be served along at least one meat course.

Kayisi Asidesinde Dana Külbasti--veal fillets seasoned with spices, originally made in 1844. Image courtesy of Asitane.

Kirma Tavuk Kebabi--grilled chicken fillets served on vinegar sautéed onions and pickled red cabbage recreated at Asitane from 1764. Image courtesy of Asitane.

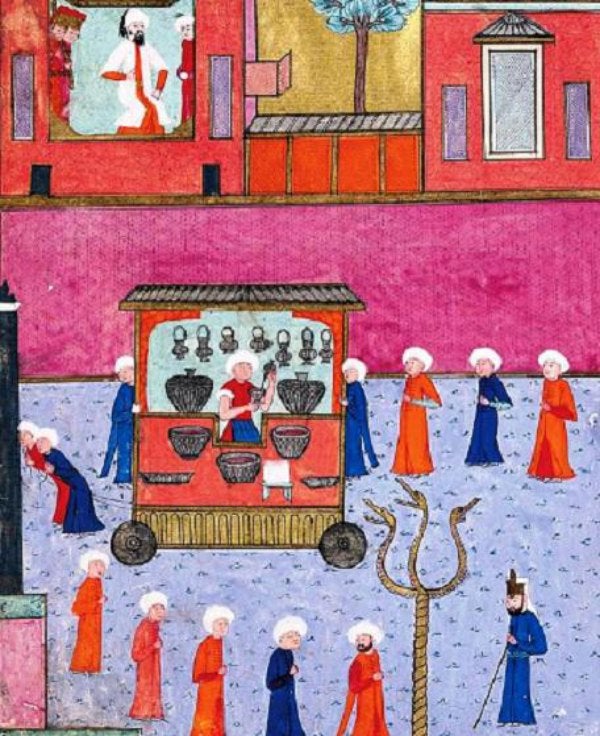

Sherbet Makers (Serbetçiler), from Surnâme-i Hümayun, Topkapi Palace Museum Library [Public Domain]

Meals ended with a decadent dessert like baklava or halva. Syrups diluted with water were served to drink, as well as sherbets made from tamarind, quince, sour cherries, and other fruits, pressed flowers including roses and violets that were mixed with lemon and sugar. As Durmay explains, to have chilled sherbet during the empire, ice would sourced from the mountains of Bursa, a city in northwestern Anatolia. Then, the ice and snow was stored by burying it deep in the gardens of the palace. Luckily, there’s refrigeration for that part now.