This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Does your sushi come with a side order of extinction? That’s certainly a possibility, as one of the most popular (and pricey) sushi ingredients has all but disappeared from many parts of the ocean. In an attempt to solve that problem (for the species, not for sushi lovers), thirteen conservation organizations this week filed a petition to protect the Pacific bluefin tuna (Thunnus orientalis) under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

The petition follows a year and a half after the Pacific bluefin was listed as vulnerable on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, a scientific assessment that does not itself provide any protections.

Both Pacific bluefin and their relatives, the Atlantic bluefin (T. thynnus), have been the subjects of protracted fights between the fishing industry and conservationists, who have warned for years now that the slow-growing predators face massive population depletions throughout their ranges.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In the case of the Pacific bluefin, conservationists say the species’ population has dropped to less than 3 percent of its historic levels due to rampant and unsustainable overfishing.

The few fish that remain today aren’t doing all that well. According to the petition nearly 98 percent of the tuna that are caught each year are now juveniles which have not yet had the chance to spawn, compromising the ability of the tuna to recover from overfishing.

“The near extinction of the Pacific bluefin is yet another example of our failure to grow—or in this case, catch—our food in a sustainable manner,” Adam Keats, a senior attorney at the Center for Food Safety, said in a prepared statement.

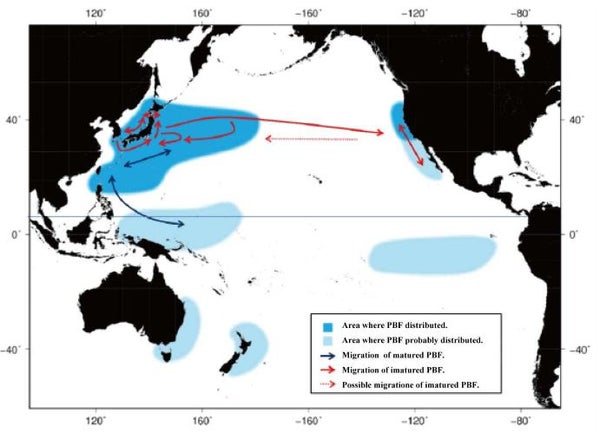

Protecting Pacific bluefin tuna under the Endangered Species Act would benefit an important portion of their population which swims along the western coast of the United States and Hawaii. Those fish also migrate back and forth across the ocean to Asia, although not all of their migration routes or behaviors are fully understood. The ESA wouldn’t do much, if anything, to protect the fish that swim in Asian waters, but it would ban exports from the U.S. to the lucrative Japanese market.

Bluefin populations and migrations. Map courtesy Center for Biological Diversity and other petitioners

Although fishing groups have resisted attempts to completely stop Pacific bluefin tuna catches, efforts to set quotas may have started to pay off, if ever so slightly. Both Mexico and Hawaii reported very small population upticks this month—half a percent in Hawaii’s case. Mexico has asked for an increase in its bluefin quota for 2017. Hawaiian fishermen, meanwhile, blame fleets from other nations for their regional population declines.

Japan, which consumes about 80 percent of Pacific bluefin, announced a new series of catch limits this past May.

Fishing isn’t the only threat faced by Pacific bluefin. The petition also cites a long list of other risks, ranging from oil development to plastic pollution and from prey depletion to aquaculture. It’s uncertain how any of those activities would be affected by an ESA listing.

The ESA listing process itself takes quite a long time, so don’t expect any government action to protect this species any time in the next couple of years. Let’s just hope the Pacific bluefin tuna can wait that long.