This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

Years come and go, but dogs are still dogs. And although dogs may appear our ever-constant companions, our scientific understanding of them is anything but set.

Each year adds to or modifies our picture of who dogs are and how to care for them, and 2017 was no different. Before 2018 comes ambling in to curl up beside you, here’s a look at a few things we learned in 2017, focusing on the fun stuff: play and puppies.

Play then and play now

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Play is often seen as an afterthought, something extra, a reward. Heck, an unnecessary bonus. Finish your homework, and then you can play. But studies suggest play isn't extra. Instead, it could be integral.

Take the relationship between play and learning: A 2017 study from the Animal Behaviour, Cognition and Welfare Group at the University of Lincoln and the University of Veterinary Medicine, Vienna, found that dogs who played after learning a task performed better on the same task the following day than dogs who had rested after learning.

The takeaway: it's not just what happens during learning that affects performance. After is valuable too. The study suggests play—an activity that is pleasant and "arousing"—could affect long- and short-term memory.

A separate team of researchers looked into the long-term value of early life puppy play and exploration experiences (and please note that anything a puppy does is intrinsically wonderful and should be filmed and shared with me at @DogSpies). The study, coming out of the Guide Dog National Breeding Centre, found that puppies—from 0-6 weeks—who received a variety of early life experiences were more cool, calm, and collected (my descriptors) later in life than dogs provided with more typical, ho-hum, early-life experiences. Guide Dogs for the Blind (UK) made a video describing their findings:

What do early-life experiences have to do with later behavior? It's the sponge factor. Young animals are a bit like fearless sponges (not that there are fearful sponges, but let's just go with it). Up until about 14 weeks, dogs are more receptive to learning about the world without being fearful of it. As a result, early-life socialization is about exposing them to a multitude of sights, smells, and sounds—without provoking excessive fear—so that they acclimate and can be more relaxed later in life. Early life socialization could help a dog conclude, "Oh that flying balloon? Balloons are so old hat. Oh, it popped? Whatever! Who cares! I was slowly introduced to the vacuum cleaner, so sounds are whatever by now."

In the study, the puppies provided with what I like to call souped-up early-life socialization showed more comfort with separations and displayed less anxiety, body sensitivity, and distractibility later in life.

The takeaway: Thousands of years of domestication have prepared dogs to live in our midst and also given them a pretty big window to acclimate to our wacky world. But individuals need individual guidance.

In fact, puppy socialization is so vital that the American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB)wrote a position statement recommending that socialization begin prior to being fully vaccinated. "Incomplete or improper socialization," they highlight, "can increase the risk of behavioral problems later in life including fear, avoidance, and/or aggression," all of which can threaten the dog-human bond and lead to relinquishment, or giving up the dog.

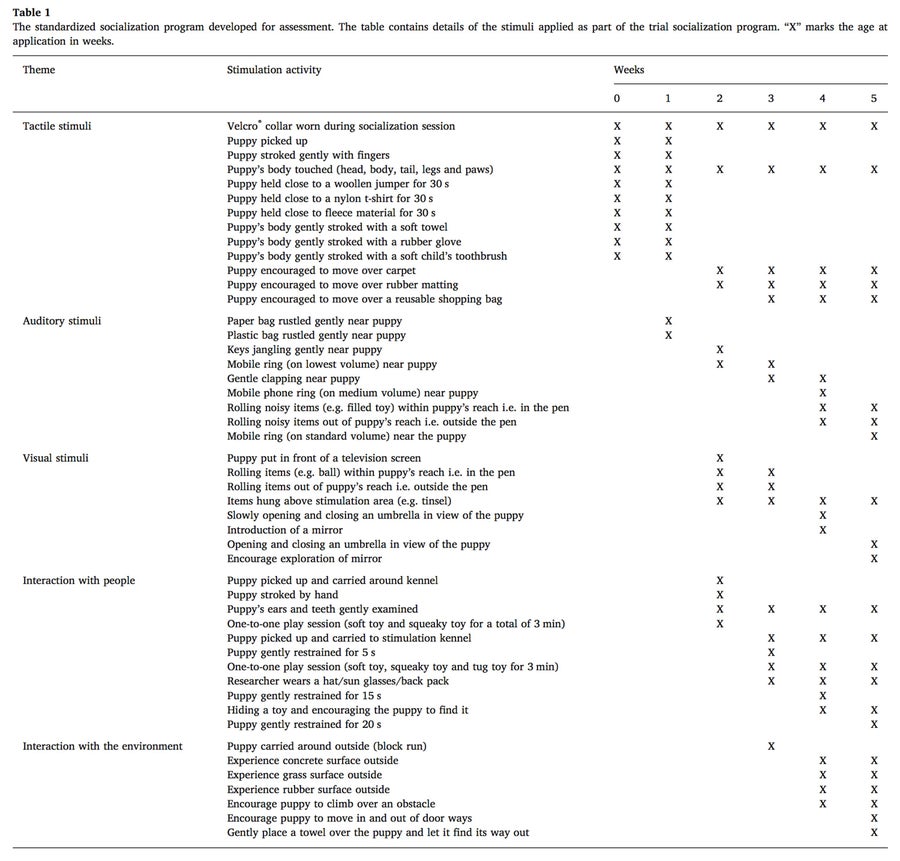

The souped-up puppy socialization program used in the study is described below and exposes puppies to tactile, auditory, and visual stimuli as well as interactions with people and the environment. The researchers note the socialization program takes between 5 and 15 minutes per puppy to execute over the different weeks. Have at it puppy people!

Table 1: Credit: Vaterlaws-Whiteside & Hartmann, 2017

No more puppies in windows

In 2017, California became the first state to ban the sale of dogs from puppy mills. To curtail the illegal puppy trade and puppy farming, the UK banned the sale of puppies without the dam (mother) present. In light of the importance of early life experiences, we all should be applauding.

Puppies born into high-volume breeders—also known as puppy mills, puppy farms, or commercial breeding establishments—make their way into homes through pet stores or online sales. In 2017, Frank McMillan of Best Friends Animal Society surveyed the research-to-date on these dogs and found they are more likely to have behavior problems as adults, most commonly aggression toward owners, strangers, or other dogs. Issues related to fear were also prevalent.

While these studies are correlational, stressors, particularly those experienced early in life, are known to "contribute to long-lasting behavioral and emotional distress." And dogs born at high-volume breeders are overrun with stressors like in utero stress, early maternal separation, early-life transport, and inadequate socialization.

The takeaway: If more states and countries follow the lead of California and the UK, 2018 can be the year where no more dogs serve as breeding dogs year after year—housed for their entire reproductive life in minimal space producing litter upon litter—and no more puppies are born in high-volume breeding facilities. A win for dogs and the people who love them.

This is the type of research we can, and should, bring with us into 2018. See you there!

References

Affenzeller, N., Palme, R., & Zulch, H. (2017). Playful activity post-learning improves training performance in Labrador Retriever dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Physiology & Behavior, 168(Supplement C), 62–73.

McMillan, F. D. (2017). Behavioral and psychological outcomes for dogs sold as puppies through pet stores and/or born in commercial breeding establishments: Current knowledge and putative causes. Journal of Veterinary Behavior: Clinical Applications and Research, 19(Supplement C), 14–26.

McMillan, F. D., Duffy, D. L., & Serpell, J. A. (2011). Mental health of dogs formerly used as ‘breeding stock’ in commercial breeding establishments. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 135(1), 86–94.

Vaterlaws-Whiteside, H., & Hartmann, A. (2017). Improving puppy behavior using a new standardized socialization program. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 197(Supplement C), 55–61.