This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

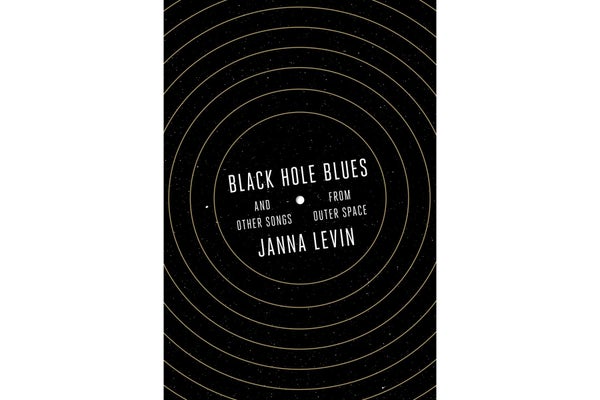

Five years ago, Janna Levin decided to write a book about black holes, gravitational waves, and the sounds of the universe. Somewhere along the way she shelved that book and wrote a different one—the fascinating, dishy inside story of the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, now well known by its acronym, LIGO. That book, Black Hole Blues And Other Songs from Outer Space, came out Tuesday, a month and a half after LIGO scientists announced that they had observed the merger of two black holes, confirming the existence of gravitational waves. A few weeks ago, Levin and I sat down to talk about it. An edited transcript of our conversation follows.

Janna Levin

Credit: Sonja Georgevich

Seth Fletcher: This is a different book from the one you originally set out to write. How did it evolve?

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Janna Levin: I gave this TED Talk in 2011, and I have this really ferocious literary agent, John Brockman. By the time I had come off the stage from talking at TED, speaking at TED about gravitational waves, somebody approached me and said, I hear you’re writing a book on this, and I laughed. I was like, Oh, my god, is Brockman here? And sure enough, Brockman was there. He was already trying to sell the book. And I thought, You know what? I can write this in my sleep. I have been researching black holes and gravitational waves for years. I was totally wrong.

I ended up doing a sabbatical at Caltech, which is LIGO headquarters, and I got so caught up in the story of LIGO. It was so much more interesting than what was familiar to me. And I ended up having this painful moment of separating from the book I originally thought I was going to write. Once I finally made that commitment, it happened.

The book is really a climbing-Mount-Everest story. It’s really about the campaign. It’s about falling and breaking your ankle and people dying on the side of the path and a 50-year summit.

SF: It seems like a miracle that LIGO was continually funded.

Janna Levin: There were many points along the road where there was real peril. But at all these perilous moments, they survived because people stepped in and played their part right when it was needed.

SF: What do you think was the darkest moment for LIGO?

Janna Levin: There were several dark moments. [Early on] there were a lot of people toiling away when there was really no guarantee that it was ever going to develop into such a huge collaboration and such a huge machine. It was really Rai [Rainer Weiss of MIT] who threw it down and said, “This can’t go on anymore. Prototypes aren’t ever going to succeed. We need to build a huge machine, and this needs to be a big science endeavor. I don’t like it. I don’t want to do it. But that’s the way it is.”

That’s when the merger happened with Kip Thorne and Rai Weiss and Ron Drever. And that was a very difficult moment, because they had to step away from the sense of, “I am the master of my own destiny and my own project, and it’s all me and my lab.” They had to form an alliance. And that was, I think, a very precarious moment. They kept bumping along, but they couldn't make decisions, because there was too much conflict between the decision makers, with no hierarchical structure. And so the next precarious moment was when the NSF [National Science Foundation] said, “Look, there's one director or this is over. You find a single director to lead the project or we're done.”

And that’s when Robbie Vogt came in and became the first director of LIGO. And as Rai says, Robbie did a lot of good. And he’ll give him that. But as somebody else said, nobody was more creative at solving a problem and nobody was more creative at creating one.

Robbie did tremendous things. First of all, he got this beautiful proposal written. He rallied the hordes, and he fought Congress for two years to get that money actually allocated. And he really did tremendous things. He saved LIGO.

But then there were horrible conflicts after Vogt’s leadership, and eventually he was fired. And that was a precarious moment. With Vogt’s resignation-slash-firing, the project absolutely could have died like the Superconducting Super Collider died. But then Barry Barish comes in. Barry is, as Kip said, the most skilled leader of large projects in the world, and he came in and saved LIGO.

SF: When did the earliest work on LIGO start? How long is this whole saga?

Janna Levin: Rai thought about it in the 1960s. It was a dream then. In the early ’70s, he built his first little prototype in something called the Plywood Palace, which was this ramshackle structure thrown onto MIT for the war effort. But I would say the real span is from 1960 something to 2015. So it’s 50 years. Fifty years!

If we go back further, we have to credit Joe Weber with starting the field. It’s a terrible story in many ways, but he really focused everyone’s minds on the idea that this could be a reality. And I want Joe to get the credit that he deserves now that there’s been a discovery.

SF: That guy’s story could be a novel.

Janna Levin: Oh, totally. I know people who want to do operas about Weber.

SF: Let’s talk about him for a minute. I don’t remember when I first heard the story of Joe Weber, who falsely claimed to have detected gravitational waves and had his career ruined as a result, but at the time I remember thinking, oh, this is some fly-by-night scientist. But that’s not even remotely true. Reading your book it’s clear that he's a serious guy who got something seriously wrong. And as you say in the book, it's basically criminal for a scientist to be wrong.

Janna Levin: Yeah, I don’t remember the exact line, but basically, it’s criminal for a scientist to be wrong. It’s vilified, for sure. You can’t make a mistake. Weber was wrong, and that was it. There was a black mark on the field. Nobody wanted to go near it again after that.

But Joe was one of the guys who first had a completely conceived idea of a maser, the predecessor to the laser, and he could have shared in the Nobel Prize for that had some things been different. He invented, really, this idea that you could [detect gravitational waves] in the laboratory. The idea of a resonant bar detector is ingenious. Joe’s idea was, basically, take a comb off a tuning fork, and it will ring when a gravitational wave passes. It’s completely ingenious, but the gravitational waves just happened to be way too weak.

But he forced people to think about it. He motivated Freeman Dyson and Roger Penrose and Stephen Hawking to think, well, could something actually be loud enough that we would ever detect it?

SF: In the run-up to the LIGO announcement, while the rumors were circulating, there was a lot of comparison to BICEP2.

Janna Levin: I think BICEP2 is very different. When BICEP2 announced its results, they always knew there was a chance that what they were detecting was something like dust. This is completely different.

The levels you would have to go to for [LIGO’s result] to not be what it looks like would be absurd. They wondered if a hacker had intentionally falsified the data, and they did a whole investigation. They interrogated some of their highest-level people to make sure nobody had falsely injected a signal.

BICEP was totally different. They did a perfectly good experiment. They actually detected something. It just happens what they detected was dust. That’s disappointing, but what they did was perfectly okay.

The problem with Weber was that nobody else was getting any detections of any kind. The skies were quiet. There were detectors all over the place in response to Weber. Weber became enormously famous at first, I think it’s important to know. People were incredibly excited about his results, and they started building bars all over the world. And not one other group claimed a detection.

Now, maybe he did detect something, and maybe it just wasn’t gravitational waves. Maybe he had seismic problems. Maybe he had instrumentation problems. I don’t think he ever intentionally misled anybody, but that is how it happened, and it was a bad turn of events for him, that’s for sure. He spent the next 25 years struggling to defend himself like a man in a criminal interview. He was very beleaguered by the end of it, and people were cruel. And I think that that’s turning. I think now the field will be much more generous towards him and his legacy.

SF: If we grant Weber the benefit of the doubt and assume he detected something, what might that something have been?

Janna Levin: Well, Supernova 1987a, which was seen with the naked eye in 1987, could conceivably ring a bar detector in this galaxy. His bars were running, so that could have been a real signal that he could have detected. But he was claiming that his bars were ringing constantly and that it was coming from the center of the galaxy, and that just isn’t supportable. If the galaxy was emitting that much energy in gravitational waves, it would have to be consuming suns worth of energy to do so and the whole galaxy would basically fragment. So there’s a lot of theoretical reason to be suspicious.

Probably he was detecting the kinds of glitches you see in the LIGO data, and statistically he was biasing towards them in unconscious ways. I mean, it’s possible they were ringing, just not for real stuff.

SF: Back to the LIGO finding, there is the simple confirmation that gravitational waves are real, but then there is the prospect of using gravitational waves as a new way of observing the universe. Are we going to get to a point where we’re recording black holes forming and merging all the time? Are we going to have a catalog of them?

Janna Levin: Yeah, I think it’s going to be that way. It eventually will become a pedestrian form of astronomy that you just don’t report about. We're going to be saying, “Oh, my god, we’ve never seen black holes that big. Why are they so big? What model of star formation allows something after it’s exploded, blown off of its entire atmosphere, collapsed to a dead star, to still be 30 times the mass of sun? How damn big was it to start with? This doesn’t match our theories.” We’ve already seen that, actually. [In LIGO’s first announced detection], there were two of these black holes, and they were both 30 solar masses.

So we’re going to start doing old-fashioned astronomy soon. And yes, there are other detections. In the data they just were low, meaning they weren’t loud enough for LIGO to trumpet them. But they seem to be there at enough significance that LIGO is saying there are other black hole detections. So that’s really interesting, because it starts to tell us how many pairs are out there. Maybe we’ve wildly underestimated, because you can’t see black holes.

SF: So what are the big questions that a gravitational-wave observatory can answer?

Janna Levin: We’ll start to learn about the population of black holes in our own galaxy and in other galaxies. And we’ll start to learn, do they merge a lot, and is that why there’s some that are millions of times the mass of the sun? Because they just kept merging, taking down gas and dust and stars but also merging with other black holes?

If that’s all this observatory does, it would justify its life. But what would be really exciting is the kind of stuff Kip dreamed about in the very early days. What if there’s something out there that we just never thought of? I mean, Galileo didn’t think of quasars when he first made a telescope. Maybe there’s stuff out there for which there are no luminous counterparts, and we’ll discover this whole dark world lurking out there, and the only evidence is the ringing of spacetime. I think that’s what a lot of us are secretly hoping for.

SF: For this book people showed you emails, letters—really impassioned, angry correspondence. Lots of drama. Have the people involved seen the book?

Janna Levin: I wrapped up the book right about the time that LIGO finished installation. The day of discovery—not knowing about the discovery—I printed the book and sent it to Kip Thorne and Rai Weiss. And they were the first two people to read it, outside of my editor, of course.

I was so anxious about doing that. But I had wonderful exchanges with them. They were just incredibly generous. I went to MIT to meet with Rai, and we went over everything and made sure all the dates were right. And even stuff he didn’t like, he said, “I don’t like that it’s in your book, but it’s true.” And I had so much respect for him for that. At no point did they ever say anything like, “take that out.” It was very much a scientist’s disposition. And Kip gave me 25 pages of incredible typed notes about the history—about John Wheeler and himself, documents and dates and exchanges with Tony Tyson. Just unbelievable stuff.

And, also, they couldn’t stand not telling me anymore, which is why they eventually told me about the discovery.

SF: When did you find out?

Janna Levin: I found out in December, after they had vetted the signal sufficiently that they felt it was definitive. When it was definitive, I got an email that was signed by David Reitze, the head of the project, the director, and Kip and Rai. It was quite a moment. It was marked “CONFIDENTIAL communication about LIGO.” I saw “confidential” and my heart started pounding. I literally leapt up. I thought, if I finish reading this, there is going to be a before and an after, and I am right on the cusp.

After I had read it, I thought, I don’t want to tell anybody. It was an absolutely overwhelming feeling, trying to viscerally believe that all of the stuff that we had written on paper and seen in math could actually have rung the detectors. I didn’t talk to anybody about it for days.

SF: Did you tell your family?

Janna Levin: No.

SF: Did you tell your editor?

Janna Levin: No. Uh-uh.

SF: So when did your publisher find out?

Janna Levin: My editor knew that something was going to be shared with me because there were rumors in the rumor mill. But I told my editor, in no uncertain terms, I’m not going to tell you what it is. And he said, all right, that’s fine. So we had an agreement that I would write an epilogue right away. Whatever they told me, if they told me it was all a bust or a fake signal or if they saw nothing, I would write the epilogue either way, but he wouldn’t get the epilogue until the final hour.

SF: So did you deliver the epilogue before or after the official announcement?

Janna Levin: I delivered it after the paper had been accepted for publication, which was the agreement I had with [LIGO spokesperson] Gaby Gonzalez. So that was a few days before before the official announcement. And probably two people in the publishing house saw it.

SF: Secretive.

Janna Levin: They deal with embargoed books over things like national secrets, so they’re quite trustworthy. I mostly didn’t tell them because Gaby asked me not to.

SF: Writing about a huge science project like this, you can obviously only include a small fraction of the people involved. Do you want to talk about how you decided to deal with that problem?

Janna Levin: There are a probably a dozen, maybe 20 people who are high up, who played major roles in this thing, and they’re not mentioned. They were absolutely essential, and their individual contributions were enormous, and I just couldn’t write about them. The book would have been illegible.

Rai and I talked about this a lot, and both Rai and I felt bad about it. We once discussed making a list of the major contributors, especially to the original design, and what they did. But we really quickly ran into a lot of political trouble, because where do you draw the line? What we decided was to publish the official author list that is on the discovery paper. We figured it was not perfect, but it was a way of acknowledging the team.