This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

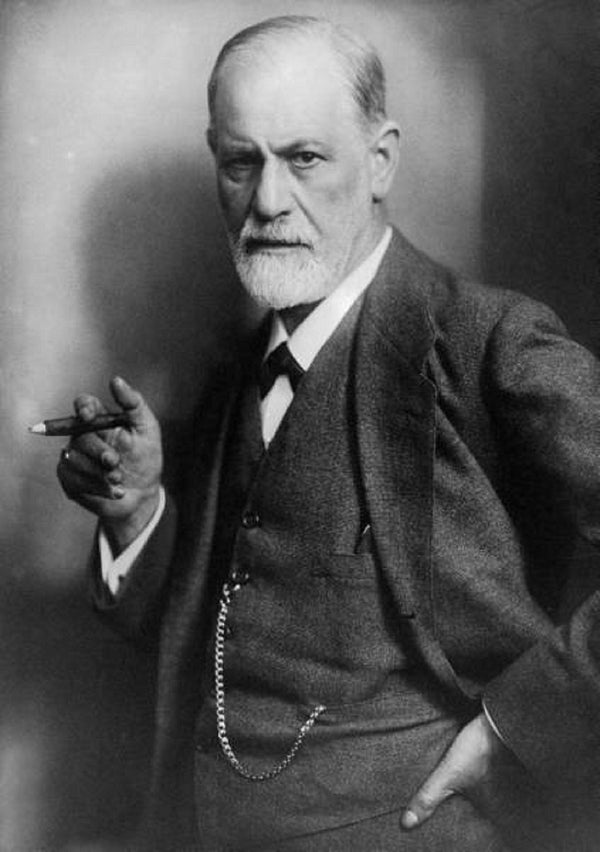

Did unconscious urges compel me to attend a debate at New York University on whether psychoanalysis, the theory/therapy invented by Freud, is relevant to neuroscience? Maybe, who the hell knows? But I definitely had conscious motives for going.

I try to make all the events of the NYU Center for Mind, Brain and Consciousness, because directors Ned Block and David Chalmers have great taste in topics and speakers. [See Further Reading for my reports on previous meetings.] The debate also gave me an excuse to trot out my old “Why Freud Isn’t Dead” meme, to which I’ll return below.

Long Live Freud!

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

First, an overview. The event featured four speakers, two critics of Freud and two boosters. I’ll begin with the boosters. Neuropsychologist Mark Solms of the University of Capetown in South Africa employs psychoanalysis as well as brain scans to understand brain-damaged patients. Solms quoted neurologist/author Oliver Sacks, who once write that “neuropsychology is admirable but it excludes the psyche—it excludes the experiencing, active, living ‘I.’”

Solms agreed, adding that modern psychiatry, with its tendency to view mental illnesses as chemical problems requiring chemical solutions, has become “proudly mindless." Psychoanalysis, Solms argued, can bring the psyche back into brain and mind science and remind us “what it is like to be a person.” Solms compared Freud to Newton and Darwin, pioneers who sketched out vast territories that others have mapped in more detail.

Like Solms, Christina Alberini has training in psychoanalysis as well as in neuroscience. She was a postdoc under Eric Kandel, who won a Nobel Prize for discovering the molecular basis of memory in snails. Kandel thinks psychoanalysis has much to offer modern mind-body researchers, and so does Alberini. She called psychoanalysis is a “rich source of information” about our unconscious and maladaptive urges.

Alberini runs a lab at NYU that explores the neural basis of memory in rodents, and psychoanalysis inspires this empirical work. For example, a fundamental Freudian tenet is that traumatic childhood experiences of which we have no explicit memory can nonetheless influence our behavior. Alberini has published evidence that shocks administered to rats in infancy, before they can form lasting memories, nonetheless have an enduring effect on their behavior.

Down with Freud!

Heather Berlin, a cognitive neuroscientist at Mount Sinai Hospital, is sympathetic toward psychoanalysis, more so than most neuroscientists. But the evidence for psychoanalysis is thin, she said, consisting mostly of anecdotes rather than systematic tests.

Psychoanalysts cite Freud as though they are quoting “scripture,” Berlin complained, and yet his ideas are so poorly defined that they are difficult to test. Concepts like “ego” and “id” are nothing but “placeholders,” like “black bile” and other humors with which medieval doctors once explained illness. Psychoanalysis seems to be no more effective at treating mental disorders than other psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Freud’s ideas, notably penis envy, Berlin asserted, reflected his biased, male perspective of his patients, primarily affluent Austrian women. When female analysts objected to the penis-envy hypothesis, Freud accused them of being in denial. Berlin was drawing attention to Freud’s obnoxious heads-I-win-tails-you-lose tactic. If you agree that you suffer from penis envy, he’s right, and if you disagree, he’s still right!

Problems like these, Berlin said, explain why modern neuroscientists rarely cite Freud or other psychoanalysts. “Neuroscience does not need psychoanalysis to validate it or to give context to its findings,” she said.

Robert Stickgold, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard, seemed especially intent on provoking Freudians in the audience. Psychoanalysis is about as useful to neuroscience, he suggested, as creationism is to evolutionary biology. The Freudians booed, but Stickgold plunged ahead. He said that Freud, who aggressively defended his theories in spite of a lack of evidence, would have been at home in the Trump administration. More boos and groans.

Freud’s ideas are not defined rigorously enough to be scientifically tested, Stickgold argued. Psychoanalysis offers no help to scientists trying to understand the brain and mind. Perhaps Freud’s ideas inspire scientists like Alberini and Solms, but so do novels and plays, and we don’t grant them scientific status.

Will Freud Ever Die?

Stickgold concluded by wondering, with exasperation, “why we’re talking about Freud.” Good question. Critics have been bashing Freud for more than a century now. And the complaints of Berlin and Stickgold are mild compared to those of, say, literary scholar Frederick Crews. He depicts Freud as a cocaine-fueled egomaniac who built his reputation by “boasting, cajoling, question begging, denigrating rivals, and misrepresenting therapeutic results.” [See my recent conversation with Crews on Meaningoflife.tv.]

But why, if Freud is so bogus, are scientists still arguing about him? Why do serious scholars still defend him, people like Solms, Alberini, Kandel and Sacks? Why does neuroscientist Christof Koch mention Freud favorably in his memoir Consciousness: Confessions of a Romantic Reductionist? Freud’s fans contend that he endures because was a pioneering genius. They see confirmations of his ideas everywhere, and they aren’t entirely delusional.

My favorite corroboration of Freud is a 1998 report in Nature, “Mothers Determine Sexual Preferences.” Kendrick et al describe an experiment in which baby goats were raised by sheep moms and baby sheep by goat moms. The baby goats, when they matured, preferred to copulate with female sheep, and the baby sheep with female goats. The study “indirectly supports Freud’s concept of the Oedipus concept,” the researchers remarked.

But Freud’s merits, such as they are, can’t entirely account for his endurance, and that brings me to my why-Freud-isn't-dead thesis. Freud lives on because science hasn’t produced a mind-body paradigm potent enough to knock him off once and for all. Freud’s critics are right, psychoanalysis is terribly flawed, but so are rival mind-body paradigms, including behaviorism, cognitive psychology, evolutionary psychology and behavioral genetics.

Neuroscience has generated voluminous findings, but theorists have failed to organize these data into a coherent, satisfying theory of the mind and brain. NYU has recently hosted workshops on Bayesian and information-based models of the mind. Each has its merits, but neither is remotely powerful enough to solve the mind-body problem once and for all.

The dominant mental-health paradigm is psychopharmacology, which views depression and other disorders as physical problems requiring physical solutions, notably medications. This is what Solms referred to as “mindless psychiatry.”

Psychopharmacology has enriched pharmaceutical companies and psychiatrists over the past few decades. But the causes of mental illness remain as obscure as ever, and there is evidence that psychiatric medications--over the long run--harm more people than they help.

If medications for mental illness were as effective as shills claim, maybe Freud would be dead. Or maybe not, because even in a world without depression and schizophrenia, we still might turn to Freud when we’re trying to make sense of our lives, just as we turn to Shakespeare and Jane Austen.

I first floated my “Why Freud Isn’t Dead” meme in Scientific American in 1996. I have reiterated it several times since then, most recently in my book Mind-Body Problems. Chapter Five, “The Meaning of Madness,” focuses on Elyn Saks, a legal scholar who overcame schizophrenia with the help of psychoanalysis and medications.

Saks has tried rival treatments, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, but she finds psychoanalysis “richer and deeper.” She calls it “the best window into the mind” and the “most interesting account of what it is to be human.” Freud was “an amazing writer,” Saks added, whose case studies “read like novels.”

Will we ever discover a paradigm potent enough to make us forget Freud? One that will satisfy our yearning to know who we really are? I hope not, because to be human means to undergo an identity crisis. I think Freud said that somewhere.

Further Reading:

Mind-Body Problems (free online edition, Kindle e-book and paperback)

Why B.F. Skinner, Like Freud, Isn’t Dead

Psychiatrists Must Face Possibility That Medications Hurt More Than They Help

Meta-Post: Posts on the Mind-Body Problem

Meta-Post: Posts on Mental Illness

See my reports on NYU meetings on integrated information theory, animal consciousness, Bayesian models of cognition and artificial intelligence.