This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

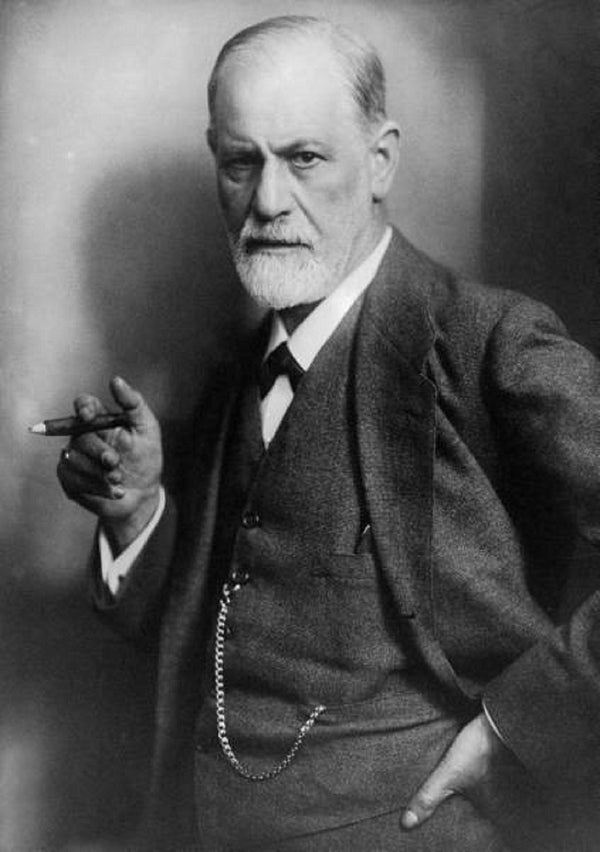

An ironic juxtaposition has me dwelling once more on Freud’s remarkable endurance. Psychoanalysis, the theory/therapy that Freud invented more than a century ago, has been bashed since its inception. Philosopher Karl Popper upheld it as a paradigmatic example of pseudo-science, and many modern scientists agree.

One of Freud’s most relentless critics is literary scholar Frederick Crews. For decades, he has attacked Freud’s character as well as his ideas--accusing him of being a cocaine-addled liar and egomaniac--in The New York Review of Books.

Last month, in that same venue, Crews renewed his assault while reviewing a biography of Freud by Elisabeth Roudinesco. Crews claims that Roudinesco, a fan of Freud, inadvertently reveals how her hero “subordinated all values to the causes of forwarding his brainchild without regard to its social or medical utility.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Roundinesco downplays Freud’s cocaine usage, Crews asserts, as well as evidence that “Freud’s early patients rejected and even mocked his sexual explanations of their troubles.” Freud “convinced millions that he belonged in the company of Copernicus and Darwin,” Crews contends, by “boasting, cajoling, question begging, denigrating rivals, and misrepresenting therapeutic results.”

So what is the “ironic juxtaposition” alluded to above? I read Crews’s review while transcribing my interview last summer with Elyn Saks, a professor of law and psychiatry at the University of Southern California. In her remarkable bestselling 2007 memoir The Center Cannot Hold: My Journey Through Madness, Saks reveals her struggles with schizophrenia.

She has been hospitalized several times for periods totaling hundreds of days. Doctors once called her prognosis “grave,” which meant that she would probably never be fully autonomous, and she would work, at best, in menial jobs.

She has nonetheless overcome her disorder with the help of medications and—you guessed it--psychoanalysis. Saks has undergone psychoanalysis since she had a psychotic breakdown at Oxford University in the late 1970s, and she plans to continue being treated for the rest of her life.

Saks, who has a Ph.D. from the New Center for Psychoanalysis, saw no contradiction between psychoanalysis and physiological approaches to the mind and its disorders. They represent two levels of “discourse,” she explained to me. “One is at the level of molecules and neurotransmitters and brain cells and so on, and the other is at the level of personality, goals, meaning.”

She is well aware of the criticism of psychoanalysis. She nonetheless finds it “richer and deeper” than alternative theories and therapies, such as cognitive-behavioral therapy. Freud, she said, was “an amazing writer. The case studies read like novels.”

Freud’s ideas, Saks noted, have spawned many rival schools of psychoanalysis. Saks’s first analyst practiced a therapy pioneered by Melanie Klein. But Freud is “the granddaddy.”

In her memoir, Saks notes that “Freud and his teachings had always fascinated me.” Psychoanalysis “asks fundamental questions: Why do people do what they do? When can people be held responsible for their actions? Is unconscious motivation relevant to responsibility?”

Saks’s affinity for psychoanalysis is part of larger trend. In her 2015 book In the Mind Fields: Exploring the New Science of Neuropsychoanalysis, journalist Casey Schwartz reports on recent attempts to find common ground between neuroscience and psychoanalysis.

In a 1996 article for Scientific American, “Why Freud Isn’t Dead,” I offered positive and negative reasons for the persistence of psychoanalysis. The positive reasons are those noted by Saks: Freud’s essays and case studies have the compelling complexity and depth of great literature.

The negative and more important reason is that science has not produced a theory/therapy potent enough to render psychoanalysis obsolete once and for all. “Freudians cannot point to unambiguous evidence that psychoanalysis works,” I wrote, “but neither can proponents of more modern treatments.”

I stand by that assessment. Critics liken psychoanalysis to phrenology, the 19th-century pseudo-science that linked personality to the shape of the skull. But if psychoanalysis is akin to phrenology, so are alternative therapies, which range from psychopharmacology and cognitive-behavioral therapy to “electro-cures” and Buddhism. As I reported recently, prescriptions for psychiatric drugs keep rising, and yet the mental health of Americans has deteriorated, according to measures such as disability payments.

In his 2016 book Schizophrenia and Its Treatment: Where Is the Progress?, Matthew Kurtz, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Wesleyan, reports that schizophrenia remains poorly understood and resistant to treatment. “[O]utcomes for people with the disorder have remained highly recalcitrant to change over the past 100 years.”

Fortunately, some treatments help some people, like Elyn Saks, overcome their illness, but our ability to explain and treat mental disorders remains primitive. Until science yields an indisputably superior theory/therapy for the mind, psychoanalysis--and Freud--will endure.

Further Reading:

Psychiatrists Must Face Possibility That Medications Hurt More Than They Help