This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

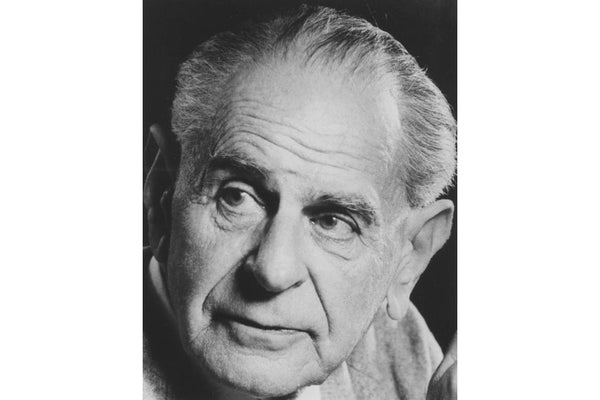

The world has been paying lots of attention to philosopher Karl Popper lately, although surely not as much as he would think he deserves. Popper, 1902-1994, railed against dogmatism in all forms. He is best-known for the principle of falsification, a means of distinguishing pseudo-scientific theories, like astrology and Freudian psychoanalysis, from genuine ones, like quantum mechanics and general relativity. The latter, Popper pointed out, make predictions that can be empirically tested. But scientists can never prove a theory to be true, Popper insisted, because the next test might contradict all that preceded it. Observations can only disprove a theory, or falsify it. In The Open Society and Its Enemies, published in 1945, Popper asserted that politics, even more than science, must avoid dogmatism, which inevitably fosters repression. Open Society has been invoked lately by those concerned about the rise of anti-democratic forces. Popper’s falsification principle has been used to attack string and multiverse theories, which cannot be empirically tested. Defenders of strings and multiverses deride critics as “Popperazzi.” [See note below on spelling.] Given the abiding interest in this complex thinker, I am posting an edited version of my profile of Popper in The End of Science. Please also check out my profiles of two other great philosophers of science, Thomas Kuhn and Paul Feyerabend. And if you like this style of journalism, keep an eye out for my new book Mind-Body Problems: Science, Subjectivity & Who We Really Are, which I plan to publish soon for free at https://mindbodyproblems.com. –John Horgan

I began to discern the paradox lurking at the heart of Karl Popper's career when, prior to interviewing him in 1992, I asked other philosophers about him. Queries of this kind usually elicit dull, generic praise, but not in Popper’s case. Everyone said this opponent of dogmatism was almost pathologically dogmatic. There was an old joke about Popper: The Open Society and its Enemies should have been titled The Open Society by One of its Enemies.

To arrange an interview, I telephoned the London School of Economics, where Popper had taught since the late 1940s. A secretary said he generally worked at his home in a London suburb. When I called, a woman with an imperious, German-accented voice answered. Mrs. Mew, housekeeper and assistant to “Sir Karl.” Before he would see me, I had to send her a sample of my writings. She gave me a list of a dozen or so books by Sir Karl that I should read before the meeting. After numerous faxes and calls, she set a date. When I asked for directions from a nearby train station, Mrs. Mew assured me that all the cab drivers knew where Sir Karl lived. “He’s quite famous.”

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“Sir Karl Popper's house, please,” I said as I climbed into a cab at the train station. “Who?” the driver asked. Sir Karl Popper? The famous philosopher? Never heard of him, the driver said. He knew the street on which Popper lived, however, and we found Popper's home, a two-story cottage surrounded by neatly trimmed lawn and shrubs, with little difficulty.

A tall, handsome woman with short dark hair, wearing black pants and shirt, answered the door. Mrs. Mew was only slightly less forbidding in person than over the telephone. As she led me into the house, she told me that Sir Karl was tired. He had endured many interviews and congratulations brought on by his 90th birthday last month, and he had been toiling over an acceptance speech for the Kyoto Prize, known as Japan's Nobel. I should expect to speak to him for only an hour at the most.

I was trying to lower my expectations when Popper made his entrance. He was stooped and surprisingly short. I had assumed the author of such autocratic prose would be tall. Yet he was as kinetic as a bantamweight boxer. He brandished an article I had written for Scientific American about how quantum mechanics is raising questions about the objectivity of physics. “I don’t believe a word of it,” he declared in a German-accented growl. “Subjectivism” has no place in physics, quantum or otherwise, he informed me. “Physics,” he exclaimed, grabbing a book from a table and slamming it down, “is that!”

He kept jumping up from his chair to forage for books or articles that could buttress a point. Striving to dredge a name or date from his memory, he kneaded his temples and gritted his teeth as if in agony. At one point, when the word "mutation" eluded him, he slapped his forehead repeatedly with alarming force, shouting, “Terms, terms, terms!”

Words poured from him so rapidly and with so much momentum that I began to lose hope that I could ask my prepared questions. “I am over 90, and I can still think,” he declared, as if I doubted it. Popper emphasized that he had known all the titans of twentieth-century science: Einstein, Schrodinger, Heisenberg. Popper blamed Bohr, whom he knew “very well,” for having introduced subjectivism into physics. Bohr was “a marvelous physicist, one of the greatest of all time, but he was a miserable philosopher, and one couldn’t talk to him. He was talking all the time, allowing practically only one or two words to you and then at once cutting in.”

As Mrs. Mew turned to leave, Popper asked her to find one of his books. She disappeared and returned empty-handed. “Excuse me, Karl, I couldn't find it,” she reported. “Unless I have a description, I can't check every bookcase.”

“It was actually, I think, on the right of this corner, but I have taken it away maybe...” His voice trailed off. Mrs. Mew somehow rolled her eyes without really rolling them and vanished.

He paused a moment, and I seized the opportunity to ask a question. “I wanted to ask you about...”

“Yes! You should ask me your questions! I have wrongly taken the lead. You can ask me all your questions first.”

I noted that in his writings he seemed to abhor the notion of absolute truths. “No no!” Popper replied, shaking his head. He, like the logical positivists before him, believed that a scientific theory can be “absolutely” true. In fact, he had “no doubt” that some current theories are true (although he refused to say which ones). But he rejected the positivist belief that we can ever know that a theory is true. “We must distinguish between truth, which is objective and absolute, and certainty, which is subjective.”

Popper disagreed with the positivist view that science can be reduced to a formal, logical system or method. A scientific theory is an invention, an act of creation, based more upon a scientist's intuition than upon pre-existing empirical data. “The history of science is everywhere speculative,” Popper said. “It is a marvelous history. It makes you proud to be a human being.” Framing his face in his outstretched hands, Popper intoned, “I believe in the human mind.”

For similar reasons, Popper opposed determinism, which he saw as antithetical to human creativity and freedom. “Determinism means that if you have sufficient knowledge of chemistry and physics, you can predict what Mozart will write tomorrow,” he said. “Now this is a ridiculous hypothesis.” Popper realized long before modern chaos theorists that not only quantum systems but even classical, Newtonian ones are unpredictable. Waving at the lawn outside the window he said, “There is chaos in every grass.”

Popper was proud of his strained relationship with his fellow philosophers, including Wittgenstein, with whom he had a run-in in 1946. Popper was lecturing at Cambridge when Wittgenstein interrupted to proclaim the “nonexistence of philosophical problems.” Popper disagreed, saying there were many such problems, such as establishing a basis for moral rules. Wittgenstein, who was sitting beside a fireplace toying with a poker, thrust it at Popper, demanding, “Give me an example of a moral rule!” Popper replied, “Not to threaten visiting lecturers with pokers,” and Wittgenstein stormed out of the room. [For other accounts of this famous episode, see the book Wittgenstein’s Poker.]

Popper abhorred philosophers who argue that scientists adhere to theories for cultural and political rather than rational reasons. Such philosophers resent being viewed as inferior to genuine scientists and are trying to “change their status in the pecking order.” Popper was particularly contemptuous of postmodernists who argued that “knowledge” is just a weapon wielded by people struggling for power. “I don't read them,” Popper said, waving his hand as if at a bad odor. He added, “I once met Foucault.”

I suggested that the postmodernists sought to describe how science is practiced, whereas he, Popper, tried to show how it should be practiced. To my surprise, Popper nodded. “That is a very good statement,” he said. “You can't see what science is without having in your head an idea what science should be.” He admitted that scientists invariably fall short of the ideal he set for them. “Since scientists got subsidies for their work, science isn't exactly what it should be. This is unavoidable. There is a certain corruption, unfortunately. But I don't talk about that.”

Popper then proceeded to talk about it. “Scientists are not as self-critical as they should be,” he asserted. “There is a certain wish that you, people like you”--he jabbed a finger at me—“should bring them before the public.” He stared at me a moment, then reminded me that he had not sought this interview. “Far from it,” he said. Popper then plunged into a technical critique of the big bang theory. “It's always the same,” he summed up. “The difficulties are underrated. It is presented in a spirit as if this all has scientific certainty, but scientific certainty doesn't exist.”

I asked Popper if he felt biologists are also too committed to Darwin's theory of natural selection; in the past he had suggested that the theory is tautological and thus pseudo-scientific. “That was perhaps going too far,” Popper said, waving his hand dismissively. “I'm not dogmatic about my own views.” Suddenly he pounded the table and exclaimed, “One ought to look for alternative theories!”

Popper scoffed at scientists’ hope that they can achieve a final theory of nature. “Many people think that the problems can be solved, many people think the opposite. I think we have gone very far, but we are much further away. I must show you one passage that bears on this.” He shuffled off and returned with his book Conjectures and Refutations. Opening it, he read his own words with reverence: “In our infinite ignorance we are all equal.”

I decided to launch my big question: Is his falsification concept falsifiable? Popper glared at me. Then his expression softened, and he placed his hand on mine. “I don't want to hurt you,” he said gently, “but it is a silly question." Peering searchingly into my eyes, he asked if one of his critics had persuaded me to pose the question. Yes, I lied. “Exactly,” he said, looking pleased.

“The first thing you do in a philosophy seminar when somebody proposes an idea is to say it doesn’t satisfy its own criteria. It is one of the most idiotic criticisms one can imagine!” His falsification concept, he said, is a criterion for distinguishing between empirical and non-empirical modes of knowledge. Falsification itself is “decidably unempirical”; it belongs not to science but to philosophy, or “meta-science,” and it does not even apply to all of science. Popper seemed to be admitting that his critics were right: falsification is a mere guideline, a rule of thumb, sometimes helpful, sometimes not.

Popper said he had never before responded to the question I had just asked. “I found it too stupid to be answered. You see the difference?” he asked, his voice gentle again. I nodded. The question seemed silly to me, too, I said, but I just thought I should ask. He smiled and squeezed my hand, murmuring, “Yes, very good.”

Since Popper seemed so agreeable, I mentioned that one of his former students had accused him of not tolerating criticism of his own ideas. Popper's eyes blazed. “It is completely untrue! I was happy when I got criticism! Of course, not when I would answer the criticism, like I have answered it when you gave it to me, and the person would still go on with it. That is the thing which I found uninteresting and would not tolerate.” In that case, Popper would throw the student out of his class.

The light in the kitchen was acquiring a ruddy hue when Mrs. Mew stuck her head in the door and informed us that we had been talking for more than three hours. How much longer, she inquired peevishly, did we expect to continue? Perhaps she had better call me a cab? I looked at Popper, who had broken into a bad-boy grin but did appear to be drooping.

I slipped in a final question: Why in his autobiography did Popper say that he is the happiest philosopher he knows? “Most philosophers are really deeply depressed,” he replied, “because they can’t produce anything worthwhile.” Looking pleased with himself, Popper glanced over at Mrs. Mew, who wore an expression of horror. Popper’s smile faded. “It would be better not to write that,” he said to me. “I have enough enemies, and I better not answer them in this way.” He stewed a moment and added, “But it is so.”

I asked Mrs. Mew if I could have the speech Popper planned to give at the Kyoto-Prize ceremony. “No, not now,” she said curtly. “Why not?” Popper inquired. “Karl,” she replied, “I've been typing the second lecture nonstop, and I'm a bit...” She sighed. “You know what I mean?” Anyway, she added, she did not have a final version. What about an uncorrected version? Popper asked. Mrs. Mew stalked off.

She returned and shoved a copy of Popper’s lecture at me. “Have you got a copy of Propensities? Popper asked her. She pursed her lips and stomped into the room next door, while Popper explained the book’s theme to me. The lesson of quantum mechanics and even of classical physics, Popper said, is that nothing is determined, nothing is certain, nothing is completely predictable; there are only “propensities” for certain things to occur. For example, Popper added, “in this moment there is a certain propensity that Mrs. Mew may find a copy of my book.”

“Oh, please!” Mrs. Mew exclaimed from the next room. She returned, no longer trying to hide her annoyance. “Sir Karl, Karl, you have given away the last copy of Propensities. Why do you do that?”

“The last copy was given away in your presence,” he declared.

“I don't think so,” she retorted. “Who was it?”

“I can't remember,” he muttered sheepishly.

Outside, a black cab pulled into the driveway. I thanked Popper and Mrs. Mew for their hospitality and took my leave. As the cab pulled away, I asked the driver if he knew whose house this was. No, someone famous, was it? Yes, Sir Karl Popper. Who? Karl Popper, I replied, one of the greatest philosophers of the 20th century. “Is that right,” murmured the driver.

When Popper died two years later, the Economist hailed him as having been “the best-known and most widely read of living philosophers.” But the obituary noted that Popper’s treatment of induction, the basis of his falsification scheme, had been rejected by later philosophers. “According to his own theories, Popper should have welcomed this fact,” the Economist noted, “but he could not bring himself to do so. The irony is that, here, Popper could not admit he was wrong.”

Can a skeptic avoid self-contradiction? And if he doesn’t, if he arrogantly preaches intellectual humility, does that negate his work? Not at all. Such paradoxes actually corroborate the skeptic’s point, that the quest for truth is endless, twisty and riddled with pitfalls, into which even the greatest thinkers tumble. In our infinite ignorance we are all equal.

Note on "Popperazzi": I originally spelled this term Popperazi, as philosopher Massimo Pigliucci does in the essay to which I link above. The more common spelling seems to be Popperazzi, and in fact Pigliucci employs that spelling at the end of his piece. You can go either way, depending on whether you see sticklers for falsification as annoying pests or scary fascists.

Further Reading:

What Thomas Kuhn Really Thought about Scientific "Truth"

Was Philosopher Paul Feyerabend Really Science's "Worst Enemy"?

Dear "Skeptics," Bash Homeopathy and Bigfoot Less, Mammograms and War More

My Modest Proposal for Solving the ‘Meaning of Life Problem’—and Reducing Global Conflict.