This article was published in Scientific American’s former blog network and reflects the views of the author, not necessarily those of Scientific American

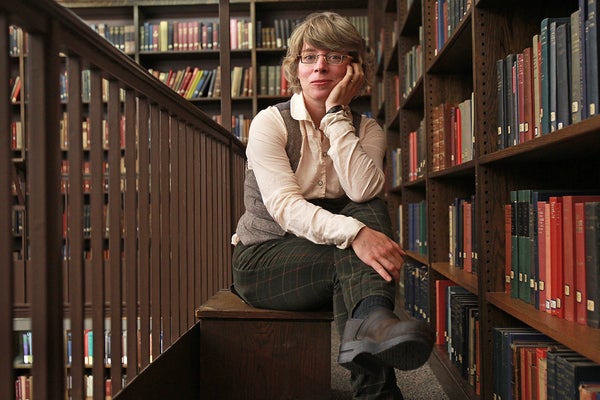

Jill Lepore, like all historians, faces a challenge. Readers of her magnificent new book, These Truths: A History of the United States, know how her story ends, so how can she keep us in suspense? She makes our foreknowledge work to her advantage, because she keeps implicitly and explicitly addressing the question, How the hell did we get here? How could a vulgar, mendacious bully who emboldens racists and sexists and xenophobes, who denounces “fake news” and is a fount of it, who embodies crass American arrogance at its worst, possibly become President?

If “whig history” shows the past leading inevitably to our enlightened present, These Truths is an anti-whig history. [See Clarification.] Lepore sought a balance, she says, between “reverence and worship, on the one hand, and irreverence and contempt, on the other.” But she clearly fears for her country, and she cannot offer assurances that all will end well. “A nation born in revolution,” she writes, “will forever struggle against chaos.” Trump’s ascent wasn’t inevitable, perhaps, but it certainly isn’t surprising, in the light of Lepore’s narrative.

Lepore traces our battles over race, gender, immigration and economic inequality—and over truth, whatever that is--back to their roots. Her title alludes to the ideal enshrined in the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…” That line has always been terribly ironic, because from the start this country’s commitment to equality excluded women, Native Americans, slaves and white men too poor to own land.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

With the possible exception of Tolstoy’s novel War and Peace, These Truths is the best historical work I’ve read, the most gripping and illuminating. Lepore is a master storyteller, offering panoramic views of battles over slavery and women’s rights and zooming in on iconic figures like Frederick Douglas and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. I can’t do justice to the scope of her 933-page epic, so I’ll dwell on one strand of it, which traces the effects, pro and con, of mass media.

The Constitution protects freedom of the press, which Benjamin Franklin and others saw as vital to the health of the newborn democracy. At its best, the press informed readers and hence made them better citizens, but it also deceived, inflamed and divided. “Newspapers in the early republic weren’t incidentally or inadvertently partisan; they were entirely and enthusiastically partisan,” Lepore states. “They weren’t especially interested in establishing facts; they were interested in staging a battle of opinions.” Sound familiar?

Optimists kept hoping advances in mass media would help us overcome our differences. “The newspaper would hold the Republic together; the telegraph would hold the Republic together; the radio would hold the Republic together; the Internet would hold the Republic together,” Lepore notes. “Each time, this assertion would be both right and terribly wrong.” Samuel Morse, inventor of the Morse code, predicted in 1855 that the telegraph would “bind man to his fellow man in such bonds of amity as to put an end to war.” Six years later the Civil War erupted.

Franklin Roosevelt recognized radio’s power to influence the public, and so did fascists. In the 1930s the Nazis mimicked the methods of American public-relations firms and even hired them to broadcast pro-German and anti-Semitic messages in the U.S. and other nations. The New York Times and other newspapers deplored this propaganda as “fake news.”

Television coverage helped turn Americans against segregation and the war in Vietnam, but these moral advances led Richard Nixon and other conservatives to accuse the media of a liberal bias, a charge that stuck. Roger Ailes, a former advisor to Nixon and Reagan, founded Fox News to “restore objectivity” to television journalism.

"Cyberutopians” promised that the Internet would unify the nation. Lepore quotes WIRED declaring in 2000 that Americans are “better educated, more tolerant, and more connected” because of the Internet. “Partisanship, religion, geography, race, gender and other traditional political divisions are giving way to a new standard—wiredness.”

The Internet, Lepore says, has indeed “accelerated scholarship, science, medicine, and education” and “aided commerce.” But it has also exacerbated economic inequality and political instability, undermined traditional media and fueled the proliferation of countless alternative “news” sites.

“New sources of news tended to be unedited,” Lepore notes, “their facts unverified, their politics unhinged… nearly all political thinking became conspiratorial.” Social media “provided a breeding ground for fanaticism, authoritarianism and nihilism. It had also proved to be easily manipulated, not least by foreign agents.”

This situation was ripe for exploitation by Trump, whom Lepore calls “a huckster chronically in and out of bankruptcy court but a reliable ratings booster on the talk show circuit.” Trump had a knack for preying on the public’s fears and the media’s desperation for drama.

Lepore blames the left as well as right for the polarization that wracks this country, and for the erosion of our commitment to free speech. Liberals have “engaged in a politics of grievance and contempt: anyone who disagreed with them was racist, sexist, classist, or homophobic—and stupid. On college campuses, they passed ‘hate speech’ codes, banning speech that they deemed offensive. They would brook no dissent.”

In a grim epilogue, Lepore reminds us of a new threat to our union, and all civilization: climate change. Average temperatures in Philadelphia, where the U.S. held its constitutional convention in 1787, have risen from 52 degrees Fahrenheit then to 59 today. And yet the U.S. President has dismissed global warming as a hoax and worked to ease restrictions on fossil-fuel emissions. Trump’s election, Lepore laments, has “sown doubts about American leadership in the world, and about the future of democracy itself.”

In a recent New Yorker essay, Lepore remains glum about the media’s decline. She notes that good journalism, which is expensive to produce, cannot compete with cheap, sensational fake news. Old as well as new media are chasing clicks to stay solvent. Lepore warns that “legacy news organizations, hardly less than startups, have violated or changed their editorial standards in ways that have contributed to political chaos and epistemological mayhem." Donation-funded outlets such as ProPublica do good work, but their influence is minuscule. Although there is “no shortage of amazing journalists,” Lepore writes, journalism “is as addled as an addict, gaunt, wasted and twitchy, its pockets as empty as its nights are sleepless.”

Since Lepore denies us a uplifting ending, I’ll do my best to provide one. These Truths shows that, in spite of our backsliding, we Americans have managed to lurch in the right direction, toward the ideal of equal rights for all. We ended slavery and segregation and avoided the extremes of communism and fascism. Women won the right to vote, and gay men and women the right to live together and marry. We elected a black man President, twice.

I even see an upside to Trump’s election. He proved that money alone doesn’t determine the outcome of elections. A media-savvy outsider can beat a better-organized and funded political machine. Progressives can do what Trump did, as Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez proved last fall. Trump also teaches us that we can never take our hard-won progress for granted. We have a lot to lose, precisely because we have come so far.

Postscript: If you’re interested in the problem of fake news, come to a lecture that I’ve organized at my school, Stevens Institute of Technology, on Wednesday, February 13. Philosophers Cailin O’Connor and James Weatherall will discuss their fascinating and important new book The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread. The lecture is free and open to the public. Stevens, in Hoboken, N.J., is just a 20 minute subway ride and walk from New York City. I hope to see you there.

Clarification: Recent examples of whig history include Steven Pinker’s Better Angels of Our Nature and Enlightenment Now, which depict reason and decency triumphing over superstition and cruelty. “Whig” is an antiquated English term for liberal or progressive.

Further Reading:

Noam Chomsky Calls Trump and Republican Allies "Criminally Insane"

Yes, Trump Is Scary, but Don't Lose Faith in Progress

Dear Rep. Ocasio-Cortez, Please Work to End War

Should We Chill Out about Global Warming?

Why You Should Choose Optimism

How the U.S. Can Help Humanity Achieve World Peace

A Pretty Good Utopia (chapter in free online book Mind-Body Problems)